Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Winners and losers in the energy transition

Moving to net zero emissions would transform the allocation of resource wealth around the world. Policymakers are starting to assess the potential economic impact

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

What the "big beautiful bill" means for US energy

-

Opinion

Inside the ‘crazy grid’

-

Opinion

The Big Beautiful Bill is close to passing

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

Commodity markets can make or break economies. In the first half of the 19th century, the booming whaling industry made New England rich, and New Bedford, Massachusetts, was probably for a while the most prosperous city in the US. But overharvesting made whaling increasingly difficult and whale oil more expensive, and it was steadily replaced for lighting and lubrication by lard, turpentine, coal gas, kerosene and eventually petroleum, after Edwin Drake struck oil in Pennsylvania in 1859.

The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank this week held their annual meetings, and the impact of commodity markets on the world economy was high on the agenda. In the short term, the surge in oil, gas, coal and metals prices is shaking up expectations about the global economic outlook over the next few years. In the long term, the transition to lower-carbon energy implies profound changes in the distribution of resource wealth around the world.

The changes to short-term prospects were set out in an update to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook. The forecast for global GDP growth has been revised down marginally to 5.9% for this year and left unchanged at 4.9% for 2022. But behind that façade of stability there are some significant regional changes, with prospects hit for some countries by the continuing impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and supply chain disruptions and boosted for others by the rise in commodity prices. Growth in the ASEAN-5 countries including Indonesia and Malaysia is now expected to be much slower than seemed likely in July, while growth in Saudi Arabia and Russia is significantly stronger.

The boost that those countries are enjoying this year is a reminder of the vital role that oil plays in their economies. But if the world is to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement, in the long term there will have to be significantly lower demand for oil, gas and coal — to varying degrees — and that will inevitably put downward pressure on prices and exporters’ revenues

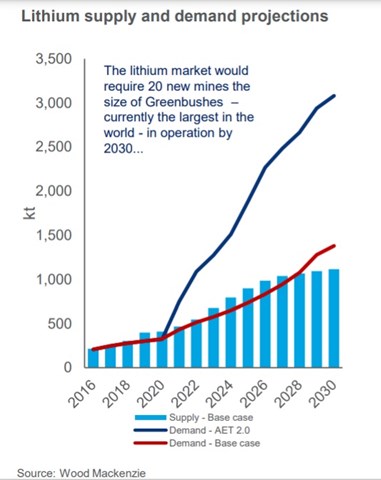

At the same time, as Wood Mackenzie’s Gavin Montgomery explained in a new briefing this week, the transition will lead to strong growth in demand for some metals, particularly the critical raw materials for batteries: lithium, cobalt and nickel. World reserves for those metals are concentrated in quite a small number of countries: Australia, Chile, The Democratic Republic of Congo, and to a lesser extent a few others including Russia and Argentina.

The energy transition holds the prospect of colossal windfalls for those metals-rich countries. Total energy-related carbon dioxide emissions need to reach net zero by around 2050 to give an even chance of staying inside the Paris agreement’s stretch goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. In a world that is on course to meet that goal, the prices of those metals “would reach historical peaks for an unprecedented, sustained period,” the IMF said this week, adding: “The prices of cobalt, lithium, and nickel would rise several hundred percent from 2020 levels.”

The is clearly bad news for the energy transition. Wood Mackenzie’s Montgomery warns that shortages and soaring prices for raw materials could pose severe challenges to the growth of electric vehicle sales. For the countries that control reserves of those metals, however, it would be a bonanza, transforming global flows of revenues from natural resources.

Over the 10 years 1999-2018, production of oil, gas and coal has generated about $70 trillion in revenues, while production of copper, lithium, generated just $3 trillion, the IMF has calculated. In a world on course for net zero emissions, those two sums could be much closer together, with the metals generating about $13 trillion over 20 years, while fossil fuel production generates about $19 trillion.

Those IMF numbers are based on projections of steep declines in oil, gas and coal prices, and look excessively pessimistic about the outlook for those revenues. But even if the specific numbers are questionable, the point holds: a Paris-aligned energy transition is a real threat to the long-term revenues of countries rich in oil, gas and coal reserves.

As the International Energy Agency this week published its 2021 World Energy Outlook, its executive director Fatih Birol argued that: “The social and economic benefits of accelerating clean energy transitions are huge, and the costs of inaction are immense.” But the IEA also acknowledged that “the transition also comes with dislocation.” In a world in which countries are implementing the net-zero pledges that they have made for the COP26 climate talks next month, about 13 million jobs would be created in low-carbon energy industries, but jobs would also be lost, including about 500,000 in oil and gas and 2 million in the coal industry worldwide. The new jobs will often require different skills and be in different places from the old jobs that are being lost, and “support must be there for those who lose jobs in declining sectors,” the IEA said.

Patrick Pouyanné, chief executive of TotalEnergies, made a similar point about the importance of “a just transition” more forcefully in a recent interview with Energy Intelligence. “In many emerging countries [oil and gas] is the source of wealth,” he said. “So the idea that you could regulate and say to developing countries, ‘leave your resource in the ground,’ without compensating them… I mean the offer from Western countries would be fair only if they said to these countries … you will get all the revenue. I didn’t read anybody who said that, we just want to regulate their future.”

To help manage the boom in demand for metals, the IMF proposes the creation of a new international institution, analogous to the IEA for energy, to “play a pivotal role in data dissemination and analysis, industry standards, and international cooperation.” That looks like a useful idea. But managing the downside of the transition will be the harder task.

Chevron sets new emissions goals

At Chevron’s annual meeting in May, an investor proposal opposed by the board requested that the company should “substantially reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of their energy products (Scope 3) in the medium- and long-term future.” That proposal was approved with 60.7% of the shareholder votes cast, and this week Chevron set out its response, becoming the first significant US oil and gas producer to set a medium-term target for the Scope 3 emissions produced when its products are used.

In its new Climate Change Resilience report, published on Monday, Chevron set out details of two new objectives: a longer-term “aspiration” to reach net zero for equity upstream Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2050, and a medium-term target to reduce the carbon intensity of its products, including Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, by 5.2% from 2016 levels by 2028.

“When we meet with investors and other stakeholders, Chevron’s approach to climate change and the energy transition is an important part of the dialogue,” the company’s lead director Ronald Sugar wrote in his introduction to the report. “At this year’s annual meeting of stockholders, the level of support for climate-related proposals indicated investors’ expectations for additional information and action.”

He added: “We believe the future of energy will be lower carbon, and we intend to be a leader in that future.”

Other US oil and gas companies have set similar long-term net zero goals. ConocoPhillips last year announced its ambition to have net zero Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2050, and Pioneer Natural Resources set out a similar ambition this year. Antero Resources has set a goal of net zero Scope 1 emissions by 2025, and Diamondback Energy says it is already at net zero on a Scope 1 basis, using carbon offsets to cover its emissions. Occidental Petroleum says it has a pathway to net-zero Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions by 2050. But Chevron is the first US oil and gas company to set a medium-term target that includes Scope 3 emissions.

Its targeted metric, called Portfolio Carbon Intensity, is based on total group emissions, in Scope 1, 2 and 3, less any carbon stored or offset, relative to total energy sales. Bruce Niemeyer, Chevron’s vice-president for strategy and sustainability, explains that that gives the company a range of options for cutting emissions, including improving efficiency, changing the portfolio, investing in low-carbon energy technologies, and using offsets. It covers the full value chain, including Scope 3 emissions from the use of products.

Mike Wirth, Chevron’s chief executive, has been very clear that he does not see opportunities for the company to create value by diversifying into wind and solar power. But the company is building operations in other low-carbon technologies including hydrogen, carbon capture and biofuels. Niemeyer says the group’s normal capital allocation process also supports lower carbon emissions. Over the next four years, two-thirds of Chevron’s upstream capital spending will be going to six assets, including the Permian and DJ basins in the US, TCO in Kazakhstan and LNG projects in Australia, which will help lower overall upstream carbon intensity.

Chevron has already cut its Portfolio Carbon Intensity significantly. It was 74.9 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule of energy sold in 2016, the baseline year, and had dropped to 71.4 gCO2e/MJ by 2020. The 2028 goal is for a further fall to 71 gCO2e/MJ. Follow This, the environmental activist investor group that filed the shareholder proposal, welcomed the move to include Scope 3 emissions, but described the target to reduce carbon intensity by 5.2% from 2016 levels as “disappointing” and “not a serious attempt to confront the climate crisis.”

Niemeyer said the target should be seen in the context of the corporate response to international climate policy. “Our first emissions targets were for 2023; our next targets are for 2028. We are on the same cycle as the Paris climate agreement. That includes a series of five-yearly reviews, and companies will have to assess what is happening on that same five-yearly cycle,” he said. “There is a progression here.”

He added that Portfolio Carbon Intensity was an indicator that could be used more widely across the industry. “What we have proposed is a relatively simple metric. Any company in the industry could use it. And people can compare the portfolio carbon intensity of different companies.”

In brief

President Vladimir Putin of Russia has denied allegations that his country is using gas as a weapon, withholding supplies from Europe to drive prices higher. Speaking at an energy forum in Moscow, he reiterated that Russia was ready to send more gas to Europe, and had already increased sales by 15% in the first nine months of 2021.

US consumers should expect much higher bills for oil, gas and power to heat their homes this winter, the Energy Information Administration has warned. “The high prices follow changes to energy supply and demand patterns in response to the Covid-19 pandemic,” the EIA said.

Purchases of diesel backup generators have been booming in some parts of California, as businesses and individuals look for ways to keep the power on in the face of wildfires and safety-related shutdowns.

Lebanon suffered a total power outage for 24 hours last weekend, leaving the country’s 6 million people without any electricity from the grid. The state electricity company said the shutdown of the country’s two main power stations was due to fuel shortages. The lights were brought back on after the army provided emergency fuel and the country’s central bank extended $100 million credit for the energy ministry to buy more.

Experts convened by the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center say that India is unlikely to meet its target of 30% of car sales being electric vehicles by 2030 due to problems including a lack of policy support and inadequate charging infrastructure.

And finally, a biofuel fit for a prince. Prince Charles, heir to the throne of the UK, gave an interview to the BBC to talk about climate change and the upcoming COP26 talks in Glasgow. It is an interesting, wide-ranging conversation, but the line that really caught on with the media was the fact that the prince’s beloved Aston Martin DB6, a present from his mother for his 21st birthday, runs on ethanol made from “surplus English white wine” and fermented whey from cheese-making. It is not exactly news: the prince revealed that the car had been converted to run on an E85 ethanol blend back in 2008. But there is obviously something irresistible about the idea of a royal car fueled by wine and cheese.

The broader point made by Prince Charles is that, although most of the vehicles on his estate are EVs, they have their limitations, and other low-carbon transport technologies, including hydrogen fuel cells, will be needed. He is right about that, but given the progress made by EVs and the bets being placed on them by manufacturers, as well as the repeated failures of advanced biofuels to live up to the hype, it looks as though the E85-enabled Aston Martin is likely to remain a rarity.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Gas and LNG: approaching a winter reckoning

Massimo Di Odoardo — Does Europe have enough gas to meet demand?

Gavin Montgomery — Why battery raw materials are a highly charged topic

Michael Barnard — Did Toyota make a mistake with hydrogen and the Mirai?

Shannon O’Neil — Mexico’s energy grid risks fading to black

William Nordhaus — Why climate policy has failed

Joyashree Roy — Bangladesh really is a climate success story

Vijaya Ramachandran and Sandeep Pai — Why India can’t wean itself off coal

Zachary Mider and Rachel Adams-Heard — An empire of dying wells

Quote of the week

“Objective number one is to develop in France, by 2030, innovative small-scale nuclear reactors with better waste management. Why put these first? Because the first issue is the production of energy. In producing energy, and in particular electricity, we have an opportunity from our historic model: our installed nuclear fleet… There are 200,000 French women and men who work in the nuclear sector, which allows us to have electricity with among the lowest CO2 emissions in Europe. We must reinvest to be at the forefront of disruptive innovation in this sector.” — President Emanuel Macron of France put nuclear power, and in particular small modular reactors, at the forefront of his France 2030 plan for reviving the country’s economy. Other energy-related measures in the ten-point plan include building at least two electrolyser “gigafactories” to become a leader in green hydrogen, making about 2 million electric and hybrid vehicles, and developing the world’s first low-carbon aircraft.

Chart of the week

This comes from the new briefing on metals demand in the energy transition by Gavin Montgomery, Wood Mackenzie’s research director for battery raw materials. It shows the demand outlook for lithium over the coming decade in two possible future scenarios. The red line shows forecast demand in our base case, representing our view of what is most likely to happen. The blue line shows the implications for lithium demand in a scenario aligned with the Paris climate agreement, consistent with limiting global warming to 2 °C. In the Paris-aligned scenario, the uptake of electric vehicles is much faster and growth in demand for lithium is much steeper than in our base case. Ramping up production fast enough to meet that demand creates a challenge for the mining industry that seems “insurmountable,” Montgomery says.