Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Is net zero by 2050 at risk?

More aggressive policy and faster investment needed

3 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Prakash Sharma

Vice President, Head of Scenarios and Technologies

Prakash Sharma

Vice President, Head of Scenarios and Technologies

Prakash leads a team of analysts designing research for the energy transition.

Latest articles by Prakash

-

The Edge

The narrowing trans-Atlantic divide on the energy transition

-

Opinion

Energy transition outlook: Asia Pacific

-

Opinion

Energy transition outlook: Africa

-

The Edge

COP29 key takeaways

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

The Edge

Artificial intelligence and the future of energy

The energy transition isn’t moving anything like fast enough so achieving global net zero by 2050 looks increasingly in doubt. To reflect the uncertainty, our Energy Transition team has added a Delayed Energy Transition Scenario to our existing range of potential outcomes. I asked VP Prakash Sharma about the team’s thinking.

Why is there a need for a ‘delayed’ scenario?

It’s a question of pragmatism – COP28 last November revealed that no major country is on track to meet its commitment to a Paris-aligned pathway of 2 °C or lower. On top of that, all governments are prioritising energy security in a world turned upside down by the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The global economy still runs on fossil fuels. The desired low-carbon energy system that the world wants, and that would eventually enhance national energy security, will take years to roll out. It will also be expensive. Capital-intensive technologies – such as green hydrogen and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) – are not commercially viable today without hefty subsidies. Higher interest rates have further eroded the economics.

Currently, politicians have little appetite for the strong policy action and investment needed to accelerate the transition. Indeed, the EU and UK governments have already pushed back 2030 goals, including delaying phaseouts on ICE cars and gas boilers. The pace and cost of the transition are likely to feature in the multiple elections around the world this year. All eyes are on November’s US presidential election – a Republican victory could threaten new technologies supported by the Inflation Reduction Act.

What does the ‘Delayed’ scenario look like?

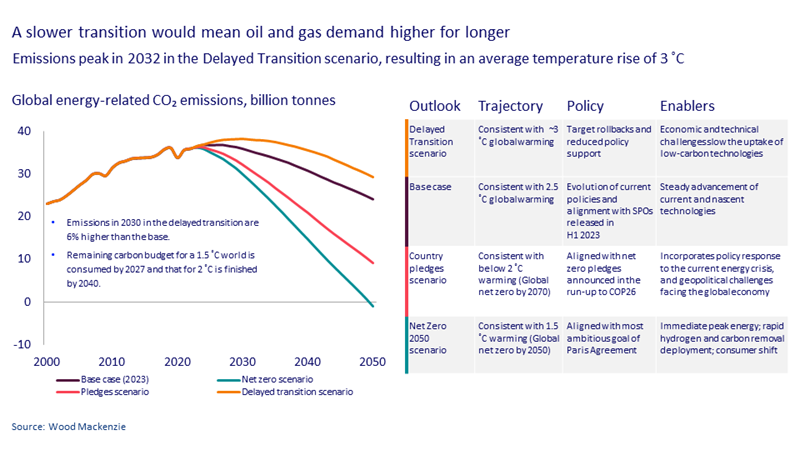

Let’s put it in perspective: our net zero by 2050 scenario, a 1.5 °C pathway, requires energy demand to peak immediately and global emissions to decline. WoodMac’s base case, still our ‘most likely’ outcome, maps a 2.5 °C pathway and assumes the evolution of current policies and a steady progression away from fossil fuels to a low-carbon energy system.

The new Delayed Transition Scenario is a 3.0 °C pathway in which global energy demand and emissions continue to rise until 2032 before declining, five years later than the base case. The carbon budget for a 1.5 °C world is consumed in the next three years.

What would it mean for the green economy?

It’ll take longer for low-carbon technologies to be scaled. The penetration rate of nascent technologies that require government support, such as EVs, green hydrogen and CCUS, lag the base case by five years. Renewables, already competitive with alternative sources of power generation, will continue to grow, albeit less quickly, and to match the lower availability of both metals supply and finance.

So, is the scenario positive for fossil fuels?

Yes, if it happens. With slower displacement by EVs, oil demand continues to increase year-on-year, reaching a peak of 114 million b/d in 2033 (compared with a 108-million b/d peak in 2030 in the base case). There are significant implications for the development of new oil supply, price and the strategic positioning of the industry at large. Gas demand, already resilient in our base case, is also higher for longer, a result of slower displacement by low-carbon alternatives. The big upstream takeovers of the last few months indicate how the industry is positioning for the possibility of resilient oil and gas demand.

Coal demand still declines from its peak in the mid-2020s, but at a gentler rate, buoyed by less coal-to-gas switching in India and China.

What would a delayed transition mean for the climate?

The Delayed Transition Scenario broadly mirrors the worrying UN ‘unchecked’ prognosis, which argues that every ecosystem will be adversely affected if average temperatures rise above 3.0 °C.

China, currently on track to reach peak emissions and energy demand before 2030, is the wild card. All bets on achieving net zero are off if the current rapid build-out of renewables in China or emerging Asian economies tails off.

Can the world avoid a climate ‘doom loop'?

We think it’s possible but are under no illusions about how tough it’s going to be. Innovation could be a game-changer, bringing viable technologies through faster than expected. Investment to scale new technologies will be key. Governments will need to look beyond short-term electioneering and put the incentives in place to unlock the capital to fund the low-carbon energy system.

Make sure you get The Edge

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers curates unique insight into the hottest topics in the energy and natural resources world.