Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Transforming the US EV battery supply chain

Will the IRA cut the umbilical cord to China?

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

The US will be hostage to no one in the energy transition. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) aims not only to incentivise and foster the development of the low-carbon technologies essential to achieving net zero but to build out the domestic supply chains to support them, too. Max Reid, Senior Analyst, shared five key takeaways for battery cell production that are central to the roll-out of electric vehicles (EVs) in the US.

First, the US has big ambitions for EVs, aiming for 50% of all light passenger vehicle sales by 2030 across battery EVs (BEVs), plug-in hybrid EVs and fuel cell EVs. Growth is already rapid with 1 million BEVs sold in 2022, up 70% year-on-year. That, though, is from a very low base. BEVs, with much the biggest share of EVs, were just 8% of total car sales and make up just 1% of stock in a market today massively dominated by ICE vehicles. Wood Mackenzie forecasts EV sales in the US to reach 5.8 million by 2030, one-third of total passenger vehicle sales. It’s only by 2034 that annual sales exceed ICE vehicles.

Second, big incentives for consumers in the IRA should speed up sales. These could reduce the purchase cost of a BEV by US$7,500 – by way of two different subsidies – on a vehicle up to a value of US$55,000.

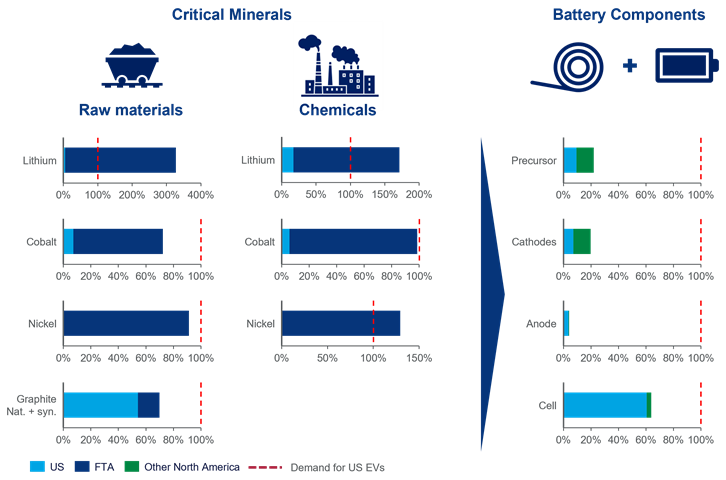

One subsidy worth US$3,750 requires the battery pack to consist of critical minerals up to a minimum value to be extracted or processed in the US, sourced from FTA (free trade agreement) partners or recycled from material in North America. The value is determined on a sliding scale rising to 80% in 2027.

The other US$3,750 requires a proportion of battery components to be manufactured or assembled in North America. The minimum threshold rises to 100% in 2028. But any involvement by ‘covered nations’ – including China and Russia – in the sourcing of critical material, battery components or manufacturing disqualifies the battery from the subsidies.

Our analysis suggests US automakers could achieve the threshold for critical minerals through 2030 by focusing on the higher-value minerals in commercial batteries – lithium, nickel and graphite. Domestic supply of these minerals is minimal but, theoretically, automakers can meet much of the demand from FTA partners. However, it’s a global market and the US will be competing with automakers from Asia and Europe for the same supply.

Battery components are an altogether bigger challenge for US automakers. China dominates the supply chain for cathodes, anodes, current collectors, solvents, additives and electrolyte salts, with over 80% market share for certain components. Achieving the threshold looks unrealistic for most BEV models for years to come. Only a small proportion of BEVs will likely qualify for the full US$7,500 incentive.

Third, to establish a domestic supply chain the IRA also offers OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) sizeable incentives. American battery manufacturers can take advantage of the advanced manufacturing production credit (AMPC), a tax credit worth US$45 per kWh, reducing by about one-third the typical battery cost of US$145 per kWh. The battery itself is between 20% and 25% of an EV’s purchase cost. We expect the AMPC will lead to a rapid build-out of giga factories as OEMs switch to domestic production to avoid the expense of shipping battery cells into the US.

Fourth, the consumer and manufacturing incentives in the IRA point to the US doubling down on the nickel-based battery chemistries that are already mainstream there. LFP batteries (lithium iron phosphate) are in the ascendancy in China. These, though, rely heavily on key components controlled by China and are likely to be marginalised in the US.

The IRA will have unintended consequences. Incentives as they stand heavily favour automakers and OEMs that have established positions and partnerships in the US, such as Tesla/Panasonic, Ford/SK On and GM/LG Energy Solution. In turn, foreign automakers and battery makers are disadvantaged. Hyundai-Kia has the second-biggest market share of BEV sales in the US, but its vehicles are manufactured in South Korea so won’t qualify for the subsidies. The Biden administration has already indicated that it’s prepared to tweak the IRA to iron out difficulties for FTA partners.

Lastly, the industry will adapt. Hyundai has already announced plans for several EV and cell plants in the US even though production won’t start until late in the decade – it has no intention of walking away from the huge US opportunity.

The IRA has lit the blue touch paper for automakers and OEMs racing to minimise battery costs and present the most competitive offerings to EV buyers. Of those 5.8 million EVs we forecast will be sold in the US in 2030, perhaps only 4%, or 300,000, will qualify for all of the incentives up for grabs, based on current supply chain bottlenecks, particularly with anodes.

The motivation for the industry to adapt to the IRA is clear. The risk for numbers, sales and the proportion qualifying for incentives are very much on the upside.

Our January 2023 Horizons assesses the opportunities across renewables and energy storage.

US could access supply of IRA-compliant minerals but battery components are a major challenge