Upstream’s biggest challenge

How to maximise value through the transition

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

How can upstream plan and build for a profitable future with oil and gas demand so uncertain? I asked Fraser McKay, Head of Upstream Analysis, and Angus Rodger, Director Upstream Research, who led our analysis in May’s Horizons, how they see the challenge.

Upstream’s a risky business – what’s the big deal?

The sheer range of possible outcomes in the transition. A gradual transition could mean oil and gas demand in 2050 is not much different to today. Upstream would continue to do what it always has for a good few decades yet – finding and developing new supply as well as generating a great deal of cash flow.

Conversely, upstream’s role would change dramatically if the world pursues a 2-degree or lower pathway. Our Accelerated Energy Transition (AET) 2 °C scenario envisages a world in 2050 in which oil demand is 70% lower than today and Brent trades at US$10 to US$18/bbl. Gas demand and prices are lower, but more resilient than oil. There will be much less need to invest in new oil supply, and upstream would be more about managing decline.

Is uncertainty affecting capital allocation?

Upstream is going to get even more short term in its investment horizon. Spend is already at a 15-year low and the focus is on short-cycle, quick-payback projects. Few companies are prepared to finance big capital-intensive and long-life projects for fear that returns will be undermined by weakening demand and prices. Fewer still are drilling the high-risk/high-reward exploration wells that lead to big discoveries.

Uncertainty related to the transition will accentuate these existing trends. The repercussions could be felt sooner rather than later. An extended period of low investment will increase the chances of a tighter oil market and higher prices later this decade should demand hold up.

Will investment shift to gas?

It’s inevitable. Today, oil still attracts almost 60% of upstream investment for one simple reason: oil projects make more money. Gas projects tend to be more capital-intensive with longer paybacks, which drags down returns. However, the world is going to need more gas so the industry must find a way to generate acceptable returns from big gas projects.

The industry needs to stop thinking of decarbonisation as a cost centre.

Could upstream be more sustainable?

Companies should be far more ambitious on Scope 1 and 2 emissions – upstream is the easiest part of the oil and gas value chain to decarbonise. Carbon pricing will help but the industry needs to stop thinking of decarbonisation as a cost centre. Most of the low-hanging fruit, such as improved facility efficiency and reduced leakage and flaring, can be value-accretive. Developing low-carbon assets, including gas, will lower portfolio carbon intensity.

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS/CCS) is a massive growth opportunity for upstream, where it can leverage its technical expertise and existing infrastructure. But success on an industrial scale will need the oil and gas industry to work in concert with big emitting onshore sectors, and governments, to develop integrated solutions.

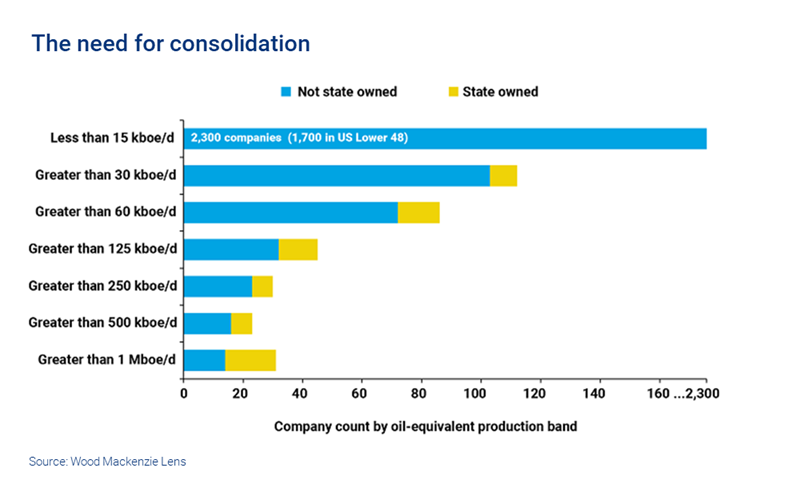

Will we need so many upstream companies?

Consolidation is well underway already, with three sizeable deals in the US L48 alone this year. As oil and gas goes moves beyond growth, this decade or beyond, companies will look for economies of scale to bolster margins.

There are 2,300 companies (1,700 in the US Lower 48) producing less than 15,000 boed. Many of these will wither away from lack of finance. Another 250 companies, IOCs, Majors and private enterprises produce more than 30,000 boed. That’s where the big consolidation opportunity lies.

How can business models change?

The industry has to adapt. We will see some upstream companies specialise – mature asset rejuvenation is one example. Private companies freer of ESG constraints could have a competitive advantage.

Bigger companies will look for ways to demonstrate value and access capital. We will see imaginative solutions – spinning off new energy or IOCs aggregating regional or thematic portfolios, as Eni/BP announced in May they intend to do in West Africa.

NOCs, which today control nearly 50% of global oil and gas production, will gain market share. Some may seek to strengthen their portfolios by selectively buying assets the Majors and other IOCs divest.

What’s the value at stake?

A huge amount. The sector is worth between US$9 trillion and US$23 trillion before taxes, based on our Lens models, while operators’ share is a still an eyewatering US$3.3 trillion to U$$8.7 trillion. These valuation ranges reflect the different oil and gas prices associated with continued demand growth and our AET-2 scenario.

As the ultimate path of the transition unfolds, the decisions that governments, NOCs, IOCs and the rest make, from talent to technology, will be critical to maximising the value of the upstream business.