How carbon pricing could reshape upstream oil and gas economics

Higher carbon charges are not a case of ‘if’ but when, where and how much — raising serious questions for investors

1 minute read

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Over 30 years, Graham has advised on taxation matters and supported complex fiscal negotiations.

Latest articles by Graham

-

Featured

Upstream fiscal 2025 outlook

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

Featured

Energy fiscal policy 2024 outlook

-

Featured

Conflicting ambitions will shape the upstream fiscal landscape in 2023 | 2023 outlook

-

Opinion

Fair share: why a new approach to mined energy transition resources is needed

-

Featured

Stage set for tougher fiscal terms for upstream operators in 2022 | 2022 outlook

To date, few countries require oil and gas producers to either pay a carbon tax or participate in an emissions trading scheme (ETS). But that could soon change. Governments around the world are on a mission to decarbonise – and may also be seeking new revenue streams to replenish Covid-19-ravaged budgets. Prudent upstream companies assume carbon charges are coming to their operations and are already building them into their models.

Our insight, Carbon pricing, fiscal terms and upstream asset values, provides detailed analysis of how carbon charges could impact asset values and transform the economics of the upstream oil and gas sector. Fill in the form to read the insight in full. Or read on for an overview of some of the key themes.

What carbon charges currently exist for the upstream sector?

Governments have two options for imposing carbon charges on upstream operations:

- Carbon tax: a fixed tax rate is applied to all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

- Emissions trading scheme (ETS): the government grants or sells emission credits which can then be traded between companies, with higher polluters potentially buying a ‘right to pollute’ from lower emitters.

Under both schemes the financial impact on specific projects can potentially be mitigated by an emissions allowance.

More than 60 carbon charge regimes currently exist at international, national and subnational levels, but very few impact major oil and gas producing areas at a rate above US$20 per tonne. Norway is the standout country for upstream carbon charges: as well as having levied a tax on CO2 since 1991, it’s a member of the EU’s ETS scheme, which was launched in 2005 and remains the world’s largest and most active.

In North America the first carbon tax for large oil and gas producers was established by the Canadian province of Alberta in 2007. British Columbia followed in 2008, with the Canadian federal government introducing a levy in 2019.

What future proposals are there for carbon charges?

In 2020, the Canadian government announced its carbon tax rate would rise steeply by 2030, to the equivalent of around US$135 per tonne. Meanwhile, after years of debate, President Biden’s green agenda is making carbon charges for upstream operations in the US far more likely.

Meanwhile, the Norwegian government’s proposal to almost triple its overall carbon tax rate on upstream oil and gas operations to over US$250 per tonne by 2030 has been grabbing headlines. It’s a bold statement, especially when you consider that Norway’s E&Ps already pay the highest carbon taxes in the world.

For detailed analysis on the implications for asset and company value, visit the store to read our report on Norway’s proposal.

What's the potential impact of stronger carbon charging regimes?

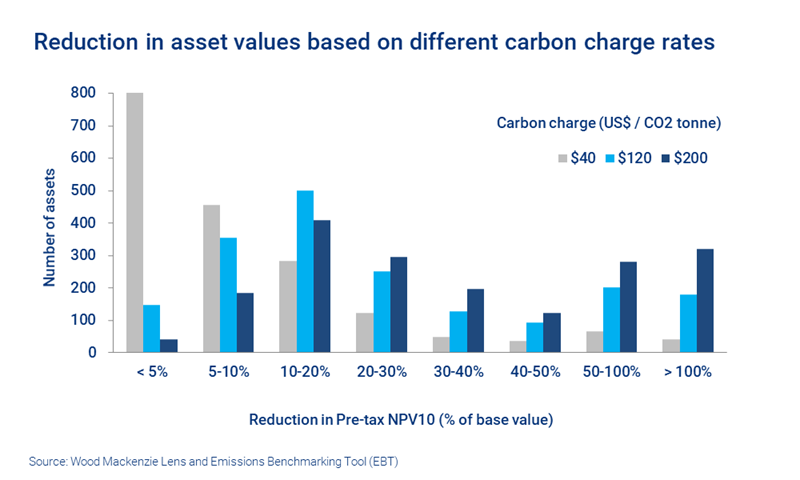

Producers have been including carbon pricing assumptions — usually between US$40 and US$100 per tonne — in their financial models for some time. We model a range of carbon prices from US$10 to US$200 per tonne in our carbon Emissions Benchmarking Tool (EBT). These are applied to the remaining lifetime CO2 emissions of over 1,800 global oil and gas assets with total reserves equating to over 1,300 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The present value of these charges is then compared with the remaining pre-tax NPV10 of each asset, included in our Lens platform. (NPV10 is the present value of the remaining net cash flow from existing assets, discounted at 10% per annum.)

What does this tell us? At US$40/tonne, most asset values are relatively insensitive to the carbon charge, although even that rate could wipe out the remaining value of some assets. But at US$200 per tonne – a lower rate than Norway is proposing for 2030 – a third of all assets would have at least 50% of their remaining value transferred in carbon charges.

Can the impact of carbon charges be mitigated to preserve asset values?

It should be noted that these figures assume all emissions are subject to any carbon charge. Actual exposure will be lower, depending on each government’s willingness to offer emissions allowances in the form of free emissions credits. This is the most important measure governments can use to modify carbon charges, thereby safeguarding asset values and lessening the impact on investment in the sector.

The other principal instrument to soften the impact of carbon charges is the ability to offset these against other payments to government.

While mitigating the impact of carbon charges is possible, it will be complicated to achieve in many jurisdictions. Countries with fiscal regimes including royalty, which is levied on gross revenue and does not allow deduction of operating costs, will be at a disadvantage relative to those with tax-centric systems. And for upstream operations governed by production sharing contracts mitigation will be even more complex.

Explore this topic in more detail

Read the insight in full to find out more about:

- The impact of new carbon charges, in charts

- Offsetting carbon charges

- Trouble ahead? Questions and challenges for investors