US tight oil – the investment dilemma

Will a cash flow bonanza lead to more drilling?

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

We thought it might never happen – but tight oil is actually going to generate free cash flow. Maligned for overpromising, under-delivering and destroying value, US Lower 48 Independents’ finances are looking rosier as capital discipline and higher oil prices work their magic. I asked Alex Beeker, Principal Analyst Corporate Research, what they’ll do with the money.

Why is tight oil generating cash flow now?

It’s pretty simple. Investment has stayed low after budgets were cut in 2020, knocking about 1 million b/d off the production peak of a year ago. But there’s still 7 million b/d from producing wells. Combined with low spend and WTI at US$60/bbl, it’s the perfect recipe for generating a lot of cash flow.

How much cash flow?

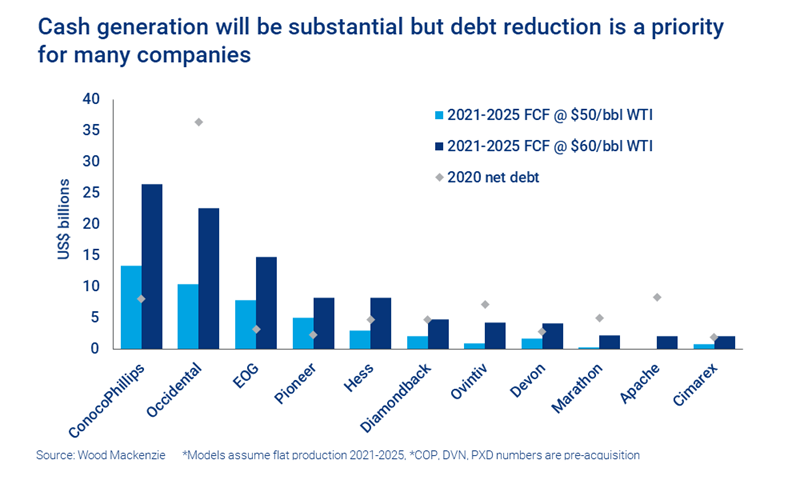

The top 10 independents will generate almost US$10 billion of free cash flow at US$50/bbl WTI over the next 12 months; and US$20 billion at US$60/bbl. We’ve made these calculations on our ‘stay flat’ framework where companies adhere to capital discipline and cap investment at around 70% of operating cash flow, some even lower. To put it in perspective, at US$60/bbl WTI, companies could double their present budgets for tight oil drilling in 2021 out of cash flow.

Is drilling picking up?

Yes. Tight oil’s short investment cycle means it’s very price-responsive. As oil prices have risen, 123 horizontal oil rigs have been added to the August 2020 nadir of 147.

We wouldn’t read too much into a bounce off the bottom. The count is still less than half the number operating a year ago and redeployment has been quite measured. On average, about five oil rigs per week have been added this year – half the rate of late 2016/early 2017, when WTI had a similar rally. Capital discipline has been working.

We reckon about 150 more oil rigs are needed just to reverse the production decline set in motion by the 2020 hiatus in drilling. At the present rate, that will take six months.

Will growing cash flows mean even more rigs?

The million-dollar question. There is no uniform answer as to what the sector will do with the cash, but debt will determine who does what.

There’s a long tail of tight oil Independents that are heavily indebted, and it may be no coincidence they typically have the poorest quality portfolios. These ‘have nots’ will be expected by their lenders (and investors) to use surplus cash to repair the balance sheet. So, no rigs for these companies. And even at US$60/bbl it will take at least three to four years for many of them to reduce gearing to 20%, a level we regard as more comfortable.

What about financially stronger companies?

The ‘haves’ – bigger, better-capitalised players – have more options. Dividends, buybacks, asset deals, and new drilling are on the table for Majors with tight oil exposure as well as a handful of Independents, including ConocoPhillips, EOG, Pioneer and Devon.

Our sense is that most still intend to keep a tight rein on spend in 2021. ExxonMobil, as the biggest and most aggressive Permian player, ran nearly 60 rigs before the price crash but just 7 to 10 rigs this year. Management said in its strategy update on 3 March that spare cash flow will go to pay down debt.

Pioneer will give more to shareholders under its variable dividend plan. If it pays out the full variable dividend at US$60/bbl (75% of US$2.0 billion free cash flow), Pioneer’s prospective dividend yield would be 7.5%, on par with the Majors.

Those that seek to increase spend – even in a disciplined, targeted way – may meet hostile resistance from investors wary of triggering another tight oil boom-and-bust cycle. EOG’s balance sheet is amongst the strongest in the sector. Yet its shares immediately fell 10% last week when it broke ranks, announcing plans to increase spend by 10% this year and set production growth targets of 8% to 10%, the highest in the sector. That chastening experience will make others think twice.

Is ‘stay flat’ a strategy?

Not for long, it’s a tiding-over strategy to keep businesses ticking as they try to curry favour with investors. Ultimately, investors will want growth, either top line or bottom line. Volume growth in a marginal producer like tight oil can be short-lived, as the two big downturns proved.

In a maturing sector like tight oil, consolidation is the likely answer. Acquisitions could be a use of future cash. We can expect the ‘haves’ to absorb the ‘have nots’, rip out more costs and reduce investment.

Can OPEC+ be more relaxed about tight oil now?

OPEC+ will be watching the US Lower 48’s recovery like a hawk. Tight oil ate OPEC’s lunch for a decade, capturing most of the contestable demand in building production up to 7% of global supply today.

The two critical questions are how high prices go and how long they stay there. The risk is that capital discipline wilts under the heat of sustained high prices, and external capital floods back into the sector. WTI at US$50 keeps US Lower 48 output flat at 9 million b/d, US$60/bbl adds 1 million by the mid-2020s and US$70/bbl another 1 million b/d.