Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Why miners won’t invest in the metals supercycle

Would a merger of Big Oil with Big Mining make sense?

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

The Big Miners, like Big Oil, are seriously flush with cash. I caught up with Julian Kettle, Vice Chair, Metals and Mining, for his thoughts on how an energy transition-led metals supercycle is evolving and what companies might do with all the money.

Has the super cycle begun?

Not yet. High metals prices in 2022 are still really about the post-pandemic bounce – demand recovery and tight supply chains exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. Even with China showing signs of economic recovery, we think there’s a downside risk to metals demand in the short term as the global economy slows. Metals prices could fall by 25% to 50% over the next two years, which, together with rising costs, will lead to a margin squeeze.

When will it kick in?

The supercycle is going to unfold through this decade and last well into next, much as we flagged almost 18 months ago. The war in Ukraine has underlined how the world’s dependence on fossil fuels will remain for some time yet. But policy announcements in the last few months from Germany and the UK show that low-carbon energy will be central both to energy security and achieving net zero in the medium term.

The energy transition will be built with metals – that’s my mantra. Electrification and the rapid growth of low-carbon technologies will drive transformational demand for key transition metals way beyond the current supply capacity. It’ll lead to a sustained period of elevated prices.

Among base metals, we see an acute need for massive new investment for copper and nickel; for cobalt and lithium, the outlook is even more extreme. Mine and refining capacity for battery raw materials needs to move to industrial scale to meet the exponential growth in demand from electric vehicles.

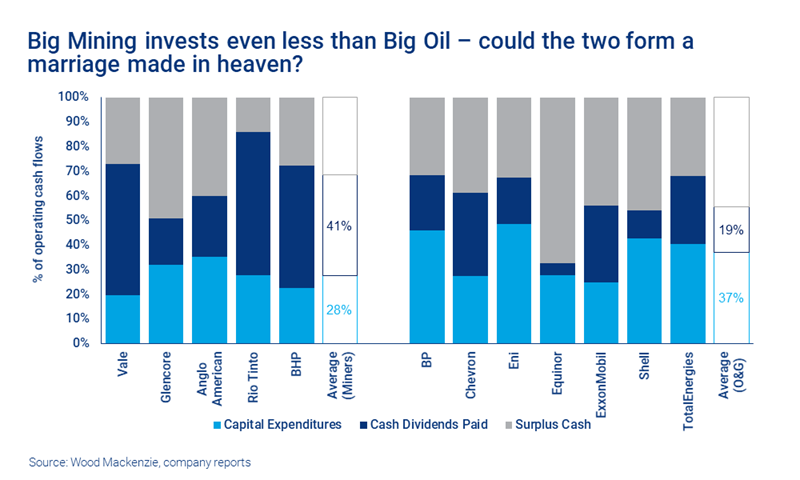

Why aren’t companies investing enough in supply?

It’s not for lack of money – most miners are generating huge amounts of cash at 2022 prices despite rising inflation. But the cash is either going onto the balance sheet or back to shareholders. Adhering to capital discipline has worked well for the sector, restoring credibility with investors and share price performance alike.

Company strategies aren’t yet focused on the growth opportunities of the energy transition. There’s little appetite for investing in big, capital-intensive new projects with long lead times nor for the perennial challenges of permitting.

Paradoxically, the slowdown and squeeze on cash flow could trigger a shift to higher investment, the deal with investors being the promise of sustained growth instead of the high returns of cash they’ve got used to. Investors will have to accept that the returns from organic growth are five to seven years into the future.

This, though, is essentially a Western problem. China continues its march to secure its energy transition raw material supply chain.

Are there many big resource opportunities?

There’s no shortage of potential projects around the world to meet metals requirements for this decade at least. The challenge is how quickly they can be brought to market. Too few are “shovel ready” and lead times can stretch to 10 years or more. When the energy transition gets into full swing and demand really picks up, project pipeline elasticity will become a constraint.

Miners also must meet increasingly stringent ESG criteria to commercialise undeveloped resources. Indonesia’s big nickel and cobalt resources are desperately needed to support the coming explosive demand growth in electric vehicles. But the high carbon footprint isn’t compatible with the low-carbon metal that the world wants.

Do you expect sector consolidation?

It’s the logical next step for a cashed-up sector, but the sector’s been down that road before and the record of value creation is patchy at best. There are comparatively few options that bring the necessary scale in energy transition metals to an industry dominated by a handful of publicly listed Mining Majors and government-owned miners. Nor is it clear that concentrating more assets in fewer hands would deliver the supply growth that’s required.

Could Big Oil and Big Mining do business together?

This is where you and I may differ. Simon, you will tell me that Big Oil doesn’t need metals and mining, there are too few synergies; investors already sceptical of the merits of diversifying into new energies would be aghast at an even more complicated business model.

But it’s a concept worth exploring. A combination between Big Oil and Big Mining would create a giant natural resources cash machine with the capital to deliver the metals investment to feed a faster transition. Mining offers similar through-cycle returns to upstream and would act as both a cyclical and structural hedge: as oil and gas demand fades, it also offers a decades-long growth opportunity.