Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Debut of the first EU carbon border tax

In December, 2022, the EU reached a provisional agreement on a first-of-its-kind Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)

Elena Belletti

Vice President, Global Head of Carbon Research

Elena Belletti

Vice President, Global Head of Carbon Research

Elena leads our carbon research, working with a growing team to help clients accelerate their energy transition journey.

Latest articles by Elena

-

Opinion

Carbon management frequently asked questions part 2: offsets

-

The Edge

COP28 key takeaways

-

Opinion

What could COP28 mean for Article 6?

-

The Edge

COP28 preview: five things to look for

-

Opinion

Debut of the first EU carbon border tax

-

Opinion

How are oil and gas companies using carbon offsets to decarbonise?

Nuomin Han

Principal Analyst, Head of Carbon Markets

Nuomin Han

Principal Analyst, Head of Carbon Markets

Nuomin provides clients with insights into emissions and climate-related development.

Latest articles by Nuomin

-

Opinion

Forecasting carbon offset use to 2050: what you need to know

-

Opinion

4 key carbon policy developments from Q1 2025

-

Featured

Carbon markets 2025 outlook

-

The Edge

COP29 key takeaways

-

Opinion

Can CCUS momentum overcome headwinds to the industry?

-

Opinion

5 things you need to know about carbon offsets in 2024

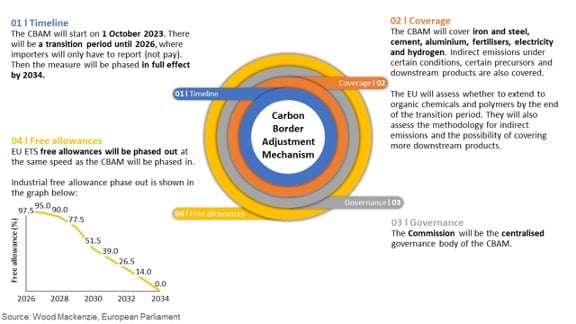

In December 2022, the EU reached a provisional agreement on a first-of-its-kind Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

The CBAM is part of the ‘Fit for 55’ climate package, the EU’s policy pathway to increase its emissions reduction commitment to at least 55% of 1990 levels by 2030.

As Wood Mackenzie pointed out in our previous analysis, the agreed shape of the CBAM is more ambitious than the initial proposal made by the European Commission, with an accelerated schedule and expanded scope.

The CBAM is a WTO-compliant way to address the risk of carbon leakage, by equalising carbon prices between domestic and foreign products. It shows the EU’s strong determination to reinforce climate commitments, but also to level the playing field between EU and non-EU producers.

The CBAM will work in parallel with the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to incentivise the clean transition outside the EU borders, including by replacing free allowances, strengthening the role of carbon pricing, and encouraging non-EU countries to lift their own climate ambitions and carbon prices.

How will the CBAM work?

Summary of the provisional agreement on the CBAM

The agreed terms are conditional on formal approval by the Parliament and Council. Look out for an update once the following essential elements of the CBAM are formally adopted and published in the EU’s Official Journal.

Which countries are covered?

Any country that is outside the coverage of the EU ETS will be subject to the CBAM. That means all non-EU countries except for Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.

To be non-discriminatory and WTO-compliant, the CBAM will apply with no exceptions. That said, the EU will use the CBAM revenue to finance decarbonisation in least developed countries to honour the ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ principle under the Paris Agreement. The financing value will correspond to at least to the level of the CBAM revenue collected.

What emissions are covered?

The CBAM will start with the selected sector and extend to all EU ETS sectors. Stationary installations in power and industrial sectors with a total rated thermal input exceeding 20MW, as well as domestic aviation are covered in the EU ETS. The full list of covered activities, threshold and greenhouse gases is in Annex I of EU ETS Directive 2003/87/EC.

The greenhouse gases covered vary for different sectors:

- CO2: electricity and heat generation, energy-intensive industries, aviation.

- N2O: production of nitric, adipic and glyoxylic acids and glyoxal.

- PFCs: production of aluminium.

As the CBAM should closely mirror the EU ETS, the coverages of the two mechanisms need to be aligned.

How are embedded emissions determined?

Embedded emissions will be determined according to the following order:

- Actual embedded emissions data, if possible

- Other than electricity, default values determined from the average emission intensity of the 10% worst performing installations in the exporting country and increase by a markup.

- Other than electricity, default values determined from the average emission intensity of the 5% worst performing EU installations for that type of goods.

- For electricity, default values determined from the 10% worst performing installations producing electricity in the third country, group of third countries or region within a third country.

How is the CBAM price determined?

The CBAM needs to closely reflect the EU ETS price. CBAM certificates are priced according to the allowances auction prices calculated weekly. The number of CBAM certificates to be surrendered will be reduced according to the explicit carbon price already paid in the origin country.

What is not answered in the provisional agreement?

More clarity is required for practical implementation:

- The current CBAM settings only impact imports into the EU, without mentioning any form of export rebates for industrial sectors in the EU. Such carbon-intensive exporting sectors must face higher carbon costs when free allowances phase out. Without compensation, such exporters are tempted to relocate outside the EU to take advantage of lower carbon prices.

- The implementation of the CBAM requires a standardised emission monitoring, recording and verification system, creating additional administrative costs, especially for exporting countries without an existing carbon pricing infrastructure. While facility-level actual emission data could be costly to attain, using country-level default values may not always be a viable option. The last available default value option uses the 5% worst performing EU installations, which is more punitive and unwelcome.

- There is no uniform approach to price emissions, and establishing the equivalency of different carbon pricing instruments remains challenging. As only explicit carbon prices paid in the export country could be deducted, the EU needs to be clear about handling other forms of less straightforward emission reduction policies, such as fuel excise tax or fuel subsidies. The other issue will be the use of carbon offset in the context of the CBAM. Carbon offsets won’t be allowed if the CBAM entirely mirror the EU ETS, creating difficulties in evaluating carbon price paid in the regimes that allow offset usage to fully or partially meet compliance obligations.

How will the CBAM push decarbonisation?

Despite the above mentioned areas, adopting the CBAM is a key step towards a cross-border approach to pricing carbon more symmetrically. The successful cross-border approach could pave the way for establishing a global minimum carbon price.

We believe the CBAM will serve the purpose of incentivising clean transitions within and outside the EU. The ripple effect will cause more carbon pricing mechanisms being implemented and/or increased domestic carbon prices in countries exposed to the CBAM.

As the CBAM rate could be as high as US$ 80-90/tCO2e for embedded emissions, the measure could also have a significant impact on trade costs. The EU may become a separate market destination after carbon cost considerations. The comparative costs may alter trade flows, with cleaner products directed to the EU and more emission-intensive products going to the rest of the world.

A niche market for cleaner trade may expand if other countries join the EU’s approach. The CBAM is setting a precedent for other countries that worry about the risk of carbon leakage under more ambitious carbon pricing regimes. The UK, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia also indicated their interest in a similar instrument.