Discuss your challenges with our solutions experts

1 minute read

By Luke Parker and Greig Aitken

The E&P space in 2050

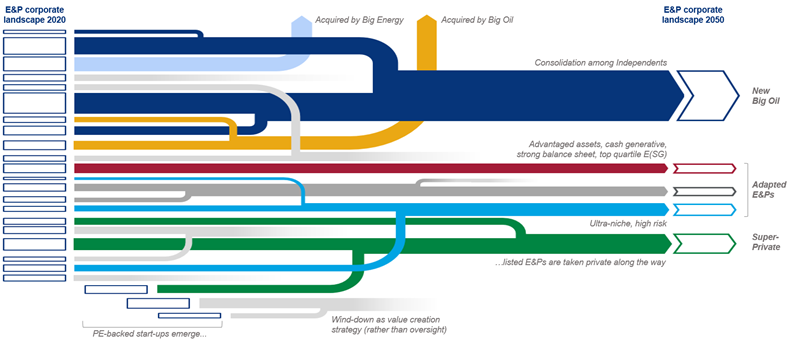

Three decades from now, the upstream corporate landscape is unrecognisable. There are far fewer Independents. In a world on a 2-degree glidepath, there may be none. Any that remain are not ‘Independents’ as we know them today.

And while 2050 may seem a lifetime away in E&P years, change is just around the corner. In that world, the number of Independents might halve over the coming decade. And halve again in the decade beyond that.

How the E&P business model loses relevance

A world on a 2-degree glidepath plainly does not need thousands of Independents chasing volume (there are currently over 8,700 oil and gas companies on our Lens platform). And in that world, creating value becomes increasingly challenging as competition for scarce capital pushes the bar progressively higher.

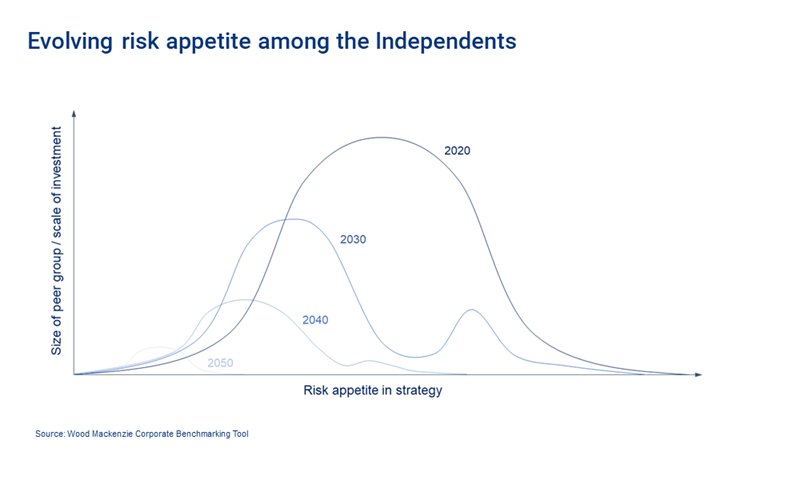

As the realities of energy transition bite, the risk-reward balance that has always been core to the E&P ‘value proposition’ becomes lopsided. Ever-fewer investors are willing to wear it. Those that do demand higher returns – debt and equity.

A shrinking investor base in oil and gas gravitates towards stable dividends, underpinned by a strong balance sheet, a low cost of capital and top-quartile E(SG) ratings.

Decarbonisation of upstream operations (as a minimum) is a given. Efficiency, margin and resilient free cash flow are prized attributes. Companies of scale, diversified across geographies and segments, are advantaged.

The Independents’ strategies evolve in parallel, as they move to minimise the risks they can control. Investment horizons get progressively shorter across the board – exploration, development, acquisition. Anything that doesn’t pay back in a narrowing timeframe – five years, three, one (short-cycle gets shorter) – is increasingly overlooked.

The very nature of the Independents changes irrevocably. As the risk-reward balance recalibrates, the ‘value proposition’ is diluted. Independents increasingly look and act like larger companies, only without the advantages of actually being a larger company. Leading ever-more investors asking themselves – what is the point of an E&P?

The journey to 2050

The long-term prognosis for the Independents remaining independent, as we know them today, is not good. But this is nothing to lament. Evolution is a constant for these companies, and there will be opportunity to create value along the way.

Clearly, there is no one-size-fits-all. The Independents are an enormously diverse group of companies. The risks they face, and their capacity to mitigate those risks, varies widely. The stance they take and the strategies they employ will also vary widely. There will be winners and losers.

Consolidation will be a defining theme

As with all mature and declining industries, consolidation will be a defining theme. It might not seem like it today, but the 2020s could be a busy decade for upstream M&A.

- Many of the most attractive Independents will combine, either as pure-plays with niche attributes at scale, or diversified ‘mini-majors’ with growing CCUS or renewables businesses.

- New Big Energy players will emerge, following the likes of Repsol in shrinking the upstream, or maybe even DONG Energy before it in exiting oil and gas completely.

- New Big Oil players will also emerge. Imagine Oxy, ConocoPhillips and Hess combine. Perhaps they re-integrate with Valero? Vertical mergers and value chain integration are a common feature of late-cycle industry consolidation.

- Big Oil will get bigger. Chevron's acquisition of Noble could be a sign of things to come. Does ExxonMobil become an aggregator in US tight oil – the operator of choice, producing 10 million b/d by 2040? And when do mega-mergers start making sense?

- The Euro Majors are on a different path. While Equinor might look like the natural owner of Lundin, or BP of Kosmos, net zero commitments – current and future – dictate that Big Energy’s oil and gas exposure will shrink (in absolute as well as relative terms).

The Independents that positioned themselves well for this future – advantaged assets, cash generative, resilient to low prices, strong balance sheet, top quartile E(SG), etc. – are best placed to evolve. They are able to remain Independent for longest, but they also make the most attractive consolidation targets. Companies with good assets but challenged structure will have less say in their own future.

Hypothetical evolution of E&P corporate landscape between 2020 and 2050

Source: Wood Mackenzie. Shows potential pathways for a ‘sample’ of 25 E&Ps. Hypothetical, for illustrative purposes.

Wind-up and wind-down

The Independents that didn’t (or couldn’t) adjust – poor assets, highly geared, marginal cash flow, (E)SG laggards – are on borrowed time. Mergers among them may prolong the inevitable, but most won’t make it to 2050 in any guise. The most challenged will disappear first. Flight to quality will embolden the next group, for a while. The better assets they leave behind will find new owners, but ever more barrels and molecules will end up stranded.

But for many Independents, wind-down will represent a strategic choice, rather than unwitting oversight. Self-liquidation – harvesting cash flow or selling off assets – is one exit route that many will take. This will be easier for private than public companies, and a prime reason for changing ownership over the coming decades (more on privatisation below).

Niche strategies and portfolios

Mounting macro risk and diminishing investor risk appetite will induce a broad shift among the Independents toward lower-risk business models. But there will still be room for alternative strategies: companies and backers – public and private – that see volatility and uncertainty as opportunity.

We may see a clear bifurcation of risk appetite and strategy over the next few decades, with specialist companies emerging in certain themes (decommissioning, high carbon assets, oil price leverage, fiscal agitators, for example).

Discover, value and model upstream assets and companies in seconds, and remain resilient in uncertain times

Find out moreOpportunistic acquisition will create value for some

Well-timed acquisitions will be a route to value creation for some over the next decade. The idea is that otherwise unloved assets generating solid cash flow can be picked up at rock-bottom prices in deals that pay-back within a matter of years. The kind of assets that are a drag on bigger players, which will be glad to have shot of them. Indeed, divergent perspectives on near-term pressures and long-term risks might create a market that works for buyers and sellers – the fabled ‘win-win’.

But this will be niche. There isn’t going to be an industry-wide liquidation event in the face of energy transition. Even the Euro-Majors, with their onerous net zero commitments, are in no rush to sell cash-generating assets below forward curve prices. On the contrary, recycling upstream cash flow into low carbon businesses is a cornerstone of the strategy. Besides, shifting ‘problem’ assets to climate-agnostic operators has limited shelf-life.

Capital intensive growth assets are another story. The type of assets that might have been considered ‘core’ until very recently – US uncons, pre-FID LNG or deep water – could find their way to market. BP, with its ambition to shrink oil and gas production by 1.1 million boe/d over the next ten years, will be the test case. Others with net-zero commitments will follow BP in downsizing upstream. Again, however, don’t expect them to give away the crown jewels. Over these timeframes, potential sellers have options and can afford to be selective.

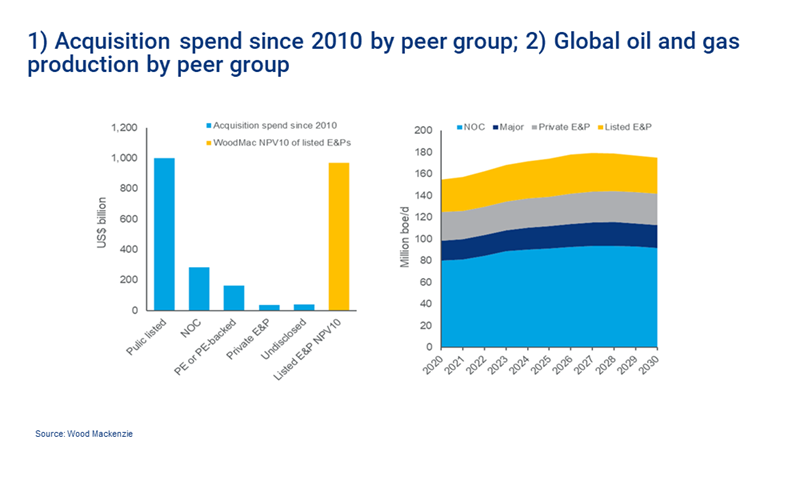

Private money will not ‘save’ the Independents

The privatisation of large swathes of the upstream is seen by many as a big part of this story. The idea is that private capital – PE, Hedge Funds, Sovereign Wealth Funds – will see opportunity in buying low-multiple, high cash flow companies that would otherwise struggle to attract new funding. Companies that will find life increasingly difficult in public hands. And that taken private – unconcerned with ‘societal licence to operate’, facing no pressure from stakeholders, with an advantaged cost of capital and different investment horizon – these companies will thrive.

While this will be a theme in the evolving corporate landscape, it will not be dominant. Don’t expect to see the entire E&P space taken private. Cost will be an issue for one. We currently value the listed Independents at nearly US$1 trillion (NPV10, US$50/bbl long-term Brent). That’s six times the amount that PE spent in upstream M&A over the past ten years. And we model US$2.5 trillion (real terms 2020) of remaining capital investment.

Perhaps more importantly, the value proposition is far from assured. The biggest risks are owner agnostic, and PE’s track record in oil and gas over the past decade – mixed at best – does not instil great confidence. Wealth holders understand this: the institutions bringing fund managers to heel also have influence on PE and Hedge Funds.

Location, location, location

Where a company is headquartered will go a long way toward dictating the pace of change. Stakeholders in different parts of the world have very different expectations. We see it in the divergent strategies of the US and European Majors, and it is increasingly evident among the Independents. That said, macro risks do not always recognise borders, and stakeholder expectations will evolve over the coming decades. Consider US tight oil, for example: large-scale consolidation is inevitable (more Devon-WPX style tie-ups), irrespective of the principle driver or exact timing.

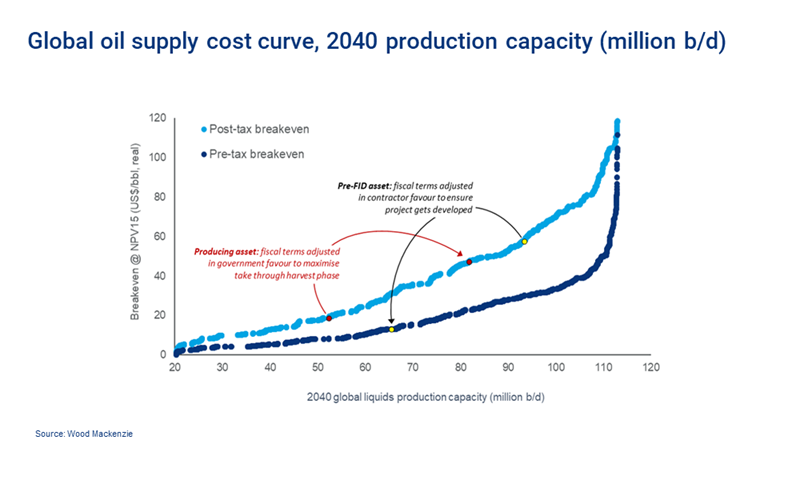

Where a company’s assets are located will be more important. We think about portfolio resilience on a post-tax basis, as things stand today. But evolving fiscal terms are a huge wildcard in all of this. The pre-tax cost curve looks very different. As the transition unfolds, some regimes will move to keep undeveloped barrels in the ground; others will do everything they can to get them out. Some will increase take through the ‘harvest’ phase; others may need to cede value to keep production flowing. Some will ban exploration; others will adopt Norway-style tax incentives.

The Independents – with a much greater degree of portfolio concentration than their larger counterparts – are particularly exposed. For many, host governments are the key stakeholders in their future. (See ‘The fiscal wildcard’ appendix for more detail).

The journey is already underway

While the destination might seem a long way off, the journey is already underway. An increasing number of Independents are, for the first time, aware of their own mortality. That realisation (in of itself) has implications for the very nature of the oil and gas industry.

It’s already apparent at the sharp end, with independent explorers becoming an increasing rarity. The days of E&P’s routinely drilling 7-to-1 shot billion-barrel prospects are long gone, and risk appetite is only headed one way from here. There is, theoretically, a role for exploration in a 2-degree world, but the message to investors – “we’re seeking the advantaged barrels” – is an increasingly hard sell when most companies are destroying value through the drill bit.

In decades past – when inexorable growth in demand was a given – the Independents didn’t need to think too far ahead. Strategies swayed in the breeze: integrated/non-integrated, oil/gas, exploration/acquisition, international/domestic, deepwater/shale, and so on. Companies could be confident that there would be more money for the next venture (or fad) – from somewhere, somehow.

In a future that threatens terminal decline and massive value destruction, the dynamic is shifting. The Independents will no longer get endless chances to re-invent themselves. Failure at the margin will, increasingly, be terminal. Explorers will only be as good as their last dry hole. Developers will only be as good as their last delayed, over-budget project. Shale players will only be as good as their last Chapter 11. And PE-backed management teams (lots may emerge as the Majors shed upstream staff) will only be as good as their last failed venture.

The journey will not be smooth…

The pace of change over the next few decades will depend, to a large extent, on how the energy transition plays out. And certain areas of the business will feel it earlier than others.

There will be points along the journey at which the rate of change accelerates. External events that seem to jolt the whole industry forward – perhaps the upcoming US election, the first Paris ratchet (‘global stocktake’ 2023), EU Green Deal milestones, China backing its 2060 net zero target with early action, some unknowable environmental calamity or clean-tech breakthrough. Coronavirus has provided such a jolt. It has, at the very least, accentuated the risk associated with energy transition and large-scale demand destruction. It may, in time, be recognised as having accelerated it.

There will also be moments when the pace of change slows, perhaps goes into reverse. Events that give individual investors and companies pause for thought – apparent setbacks to transition, an exploration success story, fiscal changes that alter the equation. There will be oil price spikes and mini-cycles. Imagine a sustained rally at a moment when other sectors are struggling, maybe tech is losing some of its lustre. In the minds of many, the risks will dissipate as opportunity comes to the fore. And some no doubt will be handsomely rewarded for their pluck in these moments.

…but the direction of travel is clear

For an ever-increasing majority of companies and stakeholders, the thought of ‘one last hurrah’ for the oil and gas industry (maybe more than one?) will not be a risk worth taking.

In the long run, the direction of travel is clear. And the longer the inevitable is delayed, the greater the threat becomes. Short-term opportunism will be for the few. To paraphrase BP CEO Bernard Looney: ‘fear of missing out’ is not the basis for strategy – it rarely ends well.