Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Negative prices reveal the crisis for US oil

The most-watched US crude futures fell below zero on Monday, in a sign of the extreme conditions facing the industry

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

The US oil market stepped through the looking glass on Monday. For the first time ever, Nymex WTI crude futures sank into negative territory, with the May 2020 contract at one point recording a price of minus $40.32 a barrel. In other words, some unwary investors were having to pay to give oil away.

These bizarre conditions lasted less than 24 hours. By the time the May contract expired on Tuesday afternoon, it had rebounded back up to $10.01 a barrel. But the fact that such freakish behaviour could break out in the most-watched US oil price is a warning of the enormous strain that the industry is under.

Federal and state authorities have been scrambling this week to find ways to relieve the pressure on the North American oil industry, and making varying amounts of progress. But market forces are already having a greater impact than any government decisions. US oil production is heading into a steep decline.

Why the oil price went negative

“Always read the small print” is a basic rule in any transaction, but it is one that some investors in oil futures have neglected. Nymex WTI futures contracts have physical settlement at Cushing, Oklahoma, so if you are left holding a long position at expiry, you have to be ready to become the proud possessor of actual crude.

It is one of those details that does not matter much, until it does. In normal times, when the US is using about 20 million barrels of oil every day, it is not too difficult to find buyers. But right now US oil consumption is down about 6 million b/d from those normal levels at a 50-year low, Wood Mackenzie analysts say. Capacity to store oil in the US is also filling up fast. We think storage at Cushing will reach effective “tank tops” — meaning it has no more usable spare capacity — in May.

On Monday, with the expiry of the May contract only about 24 hours away, investors who wanted only financial exposure to oil started to panic about the risk that they could end up with physical crude. They made a rush for the exits, and in those conditions prices can move very fast.

The CME Group, which owns the Nymex exchange, had confirmed earlier in the month that it would allow oil to trade at negative prices, and on Monday afternoon traders started to make use of that flexibility. The exchange also started to allow options with negative strike prices on Wednesday.

Harold Hamm, chairman of Continental Resources, wrote to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, urging it to investigate whether “potential market manipulation, failed systems or computer programming failures” lay behind the May contract falling into negative territory. Terry Duffy, the CME’s chief executive, rejected the suggestion that the market had not been working properly.

The rebound in WTI futures has been sharp. The June contract dipped below $10 a barrel on Tuesday, but by Friday morning was back to about $17.50 barrel. There is little cheer for the industry in that recovery, though. Today’s prices are still at a level that means a significant amount of North American production is uneconomic. With WTI at $15 a barrel, roughly 1.5 million b/d of oil produced in the US Lower 48 states does not cover its short run marginal costs.

Although the futures market may be back to positive territory, several physical crude markets in the US are not. Blends including Williston Sour, Colorado South East and NW Kansas Sweet have been trading at negative prices this week. Western Canadian Select has also been negative. There is still a real risk, too, that the disorderly market we saw this week around the May contract will reappear for the June contract as its settlement date on May 19 approaches. Hopes that that will not happen rest on there being some big changes in the supply-demand balance in the US: a strong pick-up in demand, a sharp drop-off in supply, or both. As lockdowns are extended across the US, keeping oil demand suppressed, production shut-ins are likely to accelerate.

Governments look for ways to help

President Donald Trump is clearly concerned about the impact on the industry of the oil price slump. “We will never let the great US Oil & Gas Industry down,” he tweeted on Tuesday. “I have instructed the Secretary of Energy and Secretary of the Treasury to formulate a plan which will make funds available so that these very important companies and jobs will be secured long into the future”.

Details of this promised plan, however, have yet to materialise. Senators from oil-producing states including Texas, North Dakota and Alaska wrote to Steven Mnuchin, the Treasury secretary, urging him to make sure the government’s financial support package was available to strained oil and gas companies.

Mnuchin suggested on Wednesday that the administration “may need to go back to Congress and get additional funding” for an oil industry bailout, raising the prospect of some intense horse-trading between Republicans and Democrats over their varying priorities. In an interview with Bloomberg on Thursday, he indicated there would be a dividing line between investment grade and non-investment grade oil companies. The investment grade borrowers could access the support provided by the Federal Reserve, while the others would need “alternative structures with banks”, he said.

President Trump himself suggested that reviving demand by reopening the country was “more important than any other thing that we can work on”. Ted Cruz, a US senator for Texas, agrees.

The Texas Railroad Commission has made similarly little progress on intervening in the industry. After a full day of evidence-taking last week, the three commissioners this week voted not to impose production quotas for the time being. They will revisit the issue on May 5. Ryan Sitton, the commissioner who has been the strongest advocate of using the regulator’s prorationing powers, said the quotas should be imposed “only contingent on other people” doing the same. But the longer the commission waits, the less impact any regulatory ruling will have.

New Mexico and Oklahoma took steps this week to ease the pressure on the industry in New Mexico, but neither of them has yet reached the point of imposing quotas. New Mexico said it would allow companies operating on state land to shut in production, to avoid forcing them to sell oil at low prices. Oklahoma made the same decision to allow wells to be shut in, and will consider production limits on May 11.

The market decides

While governments debate what to do, companies have been moving rapidly to cut production in North America. The number of active oil-focused rigs in the US has plunged by more than a third since mid-March, dropping by 245 to 438 last week. There have been reports of wells being plugged half-way through drilling, because it no longer made sense to reach total depth. Many companies are also taking a “frac holiday”: suspending well completions partially or completely while prices are so low.

The high decline rates in shale mean that total production will drop off quickly if there are fewer new wells being completed. If the frac holidays are extended, Wood Mackenzie’s analysts estimate, US shale production could drop by 2 million b/d between March and the end of the year.

Meanwhile, many companies are also curtailing production from wells that are already flowing. Shut-ins announced so far are expected to cut 341,000 b/d from US production in May, according to Randall Collum of Wood Mackenzie’s Genscape service. In Canada, meanwhile, shut-ins of 350,000 have already been announced, with 245,000 b/d of that in the oil sands.

For as long as demand remains weak and storage capacity is limited, oil production in North America is set to carry on falling.

The first dividend cut from an oil major in this downturn

There have been many questions raised in recent weeks about whether the large international oil companies should continue to pay such large dividends as their financial positions come under pressure. BP’s shares are yielding 10.4% and Royal Dutch Shell’s 11.3%, based on the past four quarters of dividends. Those levels suggest investors expect the payouts are likely to be cut.

Simon Flowers, Wood Mackenzie's chief analyst, highlighted the threat to the oil majors' dividends back in March, and suggested that it could be a good time to cut, when many other companies will also be reducing their payouts.

Equinor on Thursday became the first major to grasp the nettle, announcing a 67% cut in the first quarter dividend. The company’s board said in a statement that the decision reflected “the current unprecedented market conditions and uncertainties”. Having announced cuts to its capital and exploration budgets and operating costs, and suspended share buybacks, Equinor now says that it can achieve cash breakeven, before dividend payments, with oil at $25 a barrel for the rest of the year. Wood Mackenzie’s Norman Valentine described the dividend cut as “a bold act of financial prudence”.

In brief

Demand for gas in Europe’s seven largest markets this year is on course to be about 5% below pre-pandemic expectations, if lockdowns to limit the spread of the coronavirus are kept in place for three months.

NextEra Energy, the world’s largest listed utility group, plans to spend $1 billion on energy storage in 2021, making it the first company in the world to spend that much on it in a single year. The company also said its investment projects in wind and solar power would not be delayed this year, despite the pandemic.

However, there are also signs that the coronavirus-induced lockdowns are creating real hardship for some renewable energy businesses. A survey for the California Solar and Storage Association this week found that 70% of companies in the industry had cut jobs, furloughed workers, cut pay, or done some combination of the three.

Renewable energy is also facing an uncertain future in Asia. Alex Whitworth, who has responsibility for Wood Mackenzie’s power and renewables research strategy in the region, warned that potential investment in 150 gigawatts of new wind and solar capacity could be at risk, depending on how soon the pandemic is brought under control, and on whether governments continue to push for lower emissions.

The Payne Institute for Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines produced some fascinating visualisations showing how the nighttime lighting in some of the world’s great cities has changed as a result of their lockdowns to fight the coronavirus.

Food waste is building up as a result of restaurant closures and changes in consumer spending patterns. Two UK renewable energy industry groups are trying to match waste producers with anaerobic digestion plants that can use it to make biogas.

The US “has lost its competitive global position as the world leader in nuclear energy” to Russia and China, a new paper from the Trump administration’s energy department warned.

Daimler is ending its programme to develop hydrogen fuel cell cars, on the grounds that they would cost about twice as much as their battery electric vehicle equivalents.

Google has developed a new computing platform that means its data centres can work harder when more wind and solar power is available.

And finally: Michael Moore, the provocative left-wing film-maker, has produced a new documentary called Planet of the Humans, about renewable energy and climate change, which was launched on Earth Day this Wednesday. The film has received mixed reviews, with some people who you would not expect to have been Moore’s biggest fans speaking up for it.

Michael Shellenberger, president of Environmental Progress, a think-tank that supports nuclear power, praised the film on the grounds that it “exposes the complicity of climate activists in promoting pollution-intensive biomass and natural gas”. Robert Bryce was more ambivalent, saying there was plenty to admire in the way the film “skewers renewables”, but “in the end, it merely reprises a belief that has defined modern environmentalism for decades”: the idea that there are too many people on the planet. Brian Kahn in Gizmodo put it even more strongly, saying that the film is deeply flawed, and ultimately “goes full ecofascism.”

Other views

Simon Flowers — Low oil price could squeeze out 4 million b/d of non-OPEC supply

Gavin Thompson — Saudi Arabia’s price push for oil market dominance in Asia

10 factors that influence oil production shut-in decisions

James Whiteside — Batteries: powering the fight against climate change

John Kemp — Price plunge casts doubt over the future of US crude futures

Anjli Raval — Big Oil faces new reality where ‘everything has changed’

Quote of the week

“If Mr Hamm and any other commercials who are traditionally in the market believe that the price should be above zero, why would they not have stood in there and taken every single barrel of oil, if it was worth something more? The true answer is it wasn’t, at that given moment in time. Supply, demand and where you’re going to store it was the problem… The market worked the way it was supposed to work.” — Terry Duffy, chief executive of the CME Group, rejected suggestions from Harold Hamm of Continental Resources that “the system failed miserably” when the May WTI futures contract fell well below zero on Monday.

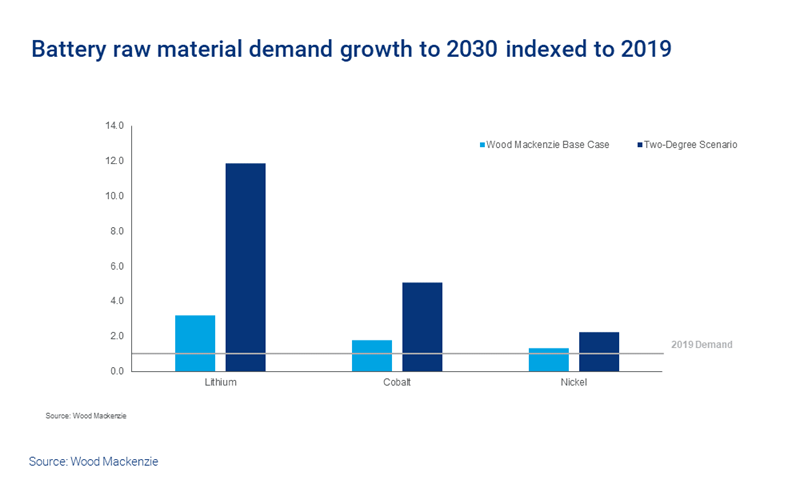

Chart of the week

This is a really important chart, from James Whiteside’s recent opinion column on lithium-ion batteries and the raw materials needed to make them. The world before the coronavirus hit was not on course to meet the 2015 Paris climate agreement goal of limiting the rise in average global temperatures to “well below” 2°C. If the world is to shift to a new course, to make that objective potentially achievable, it will almost certainly require a huge wave of electrification of road transport. And if that happens, there will be a massive increase in the demand for lithium, cobalt and nickel to make batteries. In any plan for decarbonisation, it will be vital to understand the supply chains for these metals, and to know how production can rise rapidly to meet the increased demand.