Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

One of the perennial problems with putting a price on carbon emissions is the impact on internationally competitive energy-intensive industries. If steel and cement producers in an economy that prices carbon face foreign rivals that have no curbs on emissions and hence lower energy costs, they may find it difficult to compete and ultimately be driven out of business. The net benefit for global emissions will be diminished, and could disappear altogether, as production shifts towards economies where carbon emissions are costless. Indeed, the net effect could even be to increase emissions, if output rises in more carbon-intensive countries.

Economies that adopt carbon prices can use various mechanisms to protect energy-intensive industries from the impact of their policies, but those measures are not always fully effective. In the past two decades, several countries have reported a widening gap between their emissions based on their production, and emissions based on their consumption. The EU and the US are importing more of the products that are energy-intensive and hence carbon-intensive, meaning that “embedded emissions” represented by their imports have been rising.

The phenomenon, known as carbon leakage, does not always make a huge difference to the picture of emissions around the world. Since 2000, carbon dioxide emissions have fallen in the US and the UK, and risen sharply in China, on both a production and a consumption basis. However, politicians in both Europe and the US have increasingly been focusing on the risk that such carbon leakage could undermine their climate strategies in the future. The solution that is finding a growing number of supporters is a proposed import duty euphemistically known as a “carbon border adjustment”, or more bluntly as a carbon tariff. The duty would be levied on the estimated embedded emissions, released when the product was made, to level the playing field for domestic companies facing a price on carbon.

At a time when the push for ever-freer trade has fallen out of favour with policymakers, the carbon border adjustment looks like an idea whose time has come. Joe Biden, the front-runner in the race to be the Democratic nominee for the presidency, included in his climate platform a pledge that his administration would “impose carbon adjustment fees or quotas on carbon-intensive goods from countries that are failing to meet their climate and environmental obligations.” The idea was also backed by the more than 3,500 economists supporting the Climate Leadership Council’s plan for a carbon tax and dividend system for the US.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, has similarly proposed a carbon border adjustment, starting next year, as one of the key components of her “European Green Deal” plan. Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos this month, she warned that the EU would use tariffs to prevent “carbon dumping” of products from countries that did not curb their emissions. “It is not only a climate issue; it is also an issue of fairness towards our businesses and our workers. We will protect them from unfair competition,” she said. The UK, which is leaving the union on January 31, could also potentially face the tariff if its cost of carbon drops below the cost in the EU.

One of the EU’s objectives is to push other economies into imposing their own prices on carbon. Guntram Wolff, director of Bruegel, a Brussels-based think-tank, argues that the size of the European market means that the carbon tariff would be “a powerful incentive to improve production efficiency also in third countries”.

The problem is that other countries may not be grateful for the EU’s help. Wilbur Ross, the US commerce secretary, this week indicated to the Financial Times that the carbon tariff could be another flashpoint in the Trump administration’s increasingly tense relationship with the EU over trade. “Depending on what form the carbon tax takes, we will react to it,” he said. The prospect of potential retaliation and an escalating trade war has raised concerns for some Europeans, including Germany’s influential industry association the BDI. Von der Leyen will need to build support, and bolster the courage of EU member states, if she is to get her carbon border adjustment into place.

Big Oil earnings hit by weak commodity prices

Royal Dutch Shell opened the oil majors’ reporting season with a 23% drop in earnings for 2019 to $17 billion, excluding a $4.2 billion impairment charge and other identified items. Ben van Beurden, chief executive, said the company had “demonstrated resilience and delivered good cash flow, despite a year with tough macroeconomic headwinds”.

Free cash flow for the year was $26.4 billion, after cash capital expenditure of $23.9 billion, down about 45% on a like-for-like basis from 2018. Revenues were hit by weaker oil and gas prices and a squeeze on downstream margins: Shell’s average realised prices for the year were $57.76 per barrel for oil and $4.57 per thousand cubic feet for gas, down 10% and 11% respectively from 2018. The impairments included a writedown of unconventional gas assets in the US, and of holdings in Australia and Trinidad and Tobago.

Van Beurden said Shell’s priorities for 2020 were unchanged: “We remain committed to capital discipline, as we transform Shell into a simpler company that can deliver high returns,” he said. Reuters noted that Shell’s reported reserves had fallen for six years in succession, and were now equivalent to about eight years of production, down from about 12 years in 2013.

Then on Friday it was the turn of ExxonMobil and Chevron. ExxonMobil’s shares dipped this week to their lowest level for 10 years, sending its dividend yield to its highest for 29 years, at over 5.4%, and its earnings report showed the impacts of lower commodity prices, higher production expenses, and squeezed refining margins. Earnings fell 31% to $14.3 billion for 2019, and the fall would have been steeper but for $3.9 billion of identified items, of which $3.7 billion was the gain on the sale of the non-operated upstream assets in Norway.

One striking aspect of ExxonMobil’s strategy is that capital and exploration spending rose 20% in 2019 to $31.1 billion. News earlier in the week showed one of the results of that commitment: the company’s oil discovery off the coast of Guyana just keeps getting bigger and bigger. ExxonMobil announced on Monday that it had increased its estimate of the recoverable resources on the Stabroek block to 8 billion barrels of oil equivalent, up 2 billion boe from its previous figure. The new estimate followed results from a 16th successful well on the block, where ExxonMobil’s partners are Hess and CNOOC. Production there started in December.

Chevron, meanwhile, reported an 80% drop in earnings to $2.9 billion for 2019, after a one-off charge of $10.4 billion reflecting writedowns on the value of assets including Marcellus and Utica shale reserves, the Kitimat LNG project in Canada, and the Big Foot project in the Gulf of Mexico. Excluding that charge, which was first announced last year, some other one-offs and foreign currency effects, earnings were down 23% at $11.9 billion.

Michael Wirth, chief executive, highlighted the company’s 4% increase in production to an annual average of 3.06 million barrels of oil equivalent per day; the first time in the company’s history that that figure has exceeded 3 million boe/d. Capital and exploration spending was $21 billion, including about $800 million to buy the Pasadena refinery, which meant that on an organic basis it was very close to the $20.1 billion Chevron spent in 2018.

In brief

The new coronavirus that has broken out in China and begun to spread to other countries meets the criteria for a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”, a committee of the World Health Organisation ruled on Thursday. At the time of that meeting there were 7,711 confirmed and 12,167 suspected cases in China, with a further 83 in 18 other countries. Of the confirmed cases in China, 1,370 were severe, and 170 people had died.

Yujiao Lei, a Wood Mackenzie consultant, said the coronavirus represented “a major economic risk to China and beyond”. The SARS outbreak in 2003 suggests a severe one-off impact to demand for diesel, gasoline and particularly jet fuel, and the effect may be larger because transport activity has soared since then. Chinese overseas travel, for example, has risen more than seven-fold, from 20 million trips in 2003 to about 150 million in 2018. Wood Mackenzie’s estimate is that China’s oil demand will be reduced by 250,000 barrels per day in the first quarter. That effect, plus some other factors, has led to a 500,000 b/d reduction in our forecast for global demand.

The expected slowdown in demand has hit oil prices, and Brent crude was trading on Friday at a little over $58 a barrel, down $10 a barrel from its recent peak earlier in the month. Saudi Arabia has opened talks with other OPEC members and their allies in the OPEC+ group about possibly bringing forward their next meeting from March to early February in response to the fall in crude, Reuters reported. “The Saudis want to put a floor under the oil prices, they want to do something to prevent prices from falling more,” an OPEC+ source told Reuters. China’s crude oil imports from Saudi Arabia, its leading supplier, rose by nearly 47% last year.

Venezuela is considering selling stakes in PDVSA, its national oil company, and has held talks with Repsol, Eni and Rosneft, Bloomberg reported. The proposed deal could involve a restructuring of PDVSA’s debt in exchange for oil assets, in an attempt to relieve the pressure from the country’s financial crisis.

Microsoft was praised earlier this month for its pledge to become “carbon negative” — creating no net greenhouse gas emissions — by 2030, but a story from Russell Gold in the Wall Street Journal showed the scale of the challenge it faces. Shortly after announcing its commitment, Microsoft was forced to run the diesel generators at its campus in Fargo, North Dakota, for five hours to keep the lights and the heating on, as power demand in the area surged.

The world’s car output may have passed a peak in 2017 and could remain weak until at least 2025, according to Volkmar Denner, chief executive of the automotive parts group Bosch.

And finally: Elon Musk must have been feeling light-hearted this week following the surge in Tesla’s share price and the company’s second successive quarterly profit. He decided to take some time out to record a song, and announced it on Twitter on Thursday evening. It is probably fair to say he should not give up the day job.

Other views

Simon Flowers — What the energy world looks like in 2030

Gavin Thompson — How Asia’s NOCs can learn to stop worrying and love the energy transition

Julia Pyper — Dispatch from Abu Dhabi: the many meanings of “energy transition”

Gideon Rachman — China, not America, will decide the fate of the planet

Nick Butler — The disruptive effects of Europe’s Green Deal

Michael Dobson — Revisiting OPEC’s democratic roots in the age of climate emergency

Robin Mills — How oil transformed Norway

Noah Kaufman — Dear Republicans: Innovation isn’t climate policy

Quote of the week

"I meet with shareholders and they say: ‘We would like you to move really quickly into renewables’. And I say: ‘Well, we can do that. Would you like us to cut the dividend?’ They're like: ‘No, no, don't do that.’ So we've got to find the right balance and pace here." — Bob Dudley, who is stepping down as chief executive of BP after nine years, discussed the dilemma the company faces in the energy transition, in an interview with Jason Bordoff of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. The interview is full of interesting points, and well worth listening to in full.

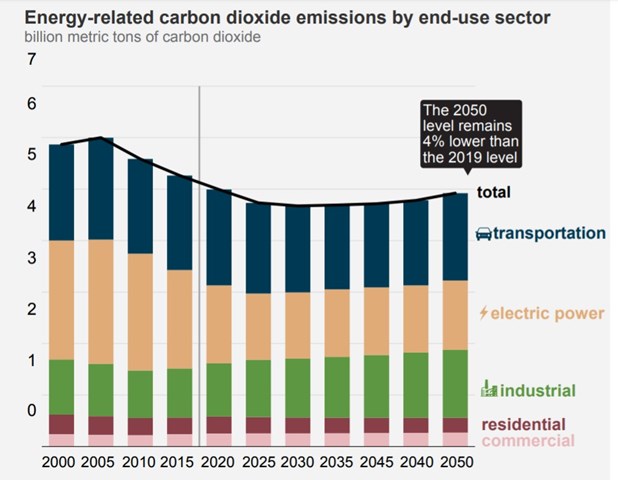

Chart of the week

This comes from the US Energy Information Administration’s new Annual Energy Outlook, which gives projections for the US out to 2050. The outlook is full of interesting information, and sure to spark debates about its view of the next three decades. For example, the EIA projects very little electrification of road transport in the US, with electricity still accounting for less than 2% of transport fuel consumption in 2050. As a result, it expects gasoline demand to be resilient, falling only 17% over the next 30 years, while jet fuel consumption is expected to rise 31%. Meanwhile, coal-fired power generation is expected to remain in a steep decline until about 2025, but then stabilise and remain resilient to 2050, while gas-fired power is expected to grow by 23%. The result is this pattern for expected US energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, which decline to about 2030 and then start rising again. By 2050, emissions are predicted to be 4% lower than in 2019. Compare that to Britain and France, which have passed legislation setting targets of net zero emissions by that date.

How to get Energy Pulse

Energy Pulse is Ed Crooks' weekly column, published by Wood Mackenzie every Friday. Here's how to get Energy Pulse:

- Follow us on social media @WoodMackenzie on Twitter or Wood Mackenzie on LinkedIn

- Fill in the form at the top of this page and we'll send you an email when the latest issue goes live

- Bookmark this page to have access to the full archive of Energy Pulse