The road to COP26

While the urgent crisis of the pandemic has been dominating the headlines, the slower-moving threat of climate change has prompted a wave of activity from governments and businesses

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

-

Opinion

What the conflict between Israel and Iran means for energy

This is a big year for climate policy. The Paris agreement of 2015 set up a five-yearly cycle for countries to increase the ambition of their goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions. So right from the outset, the COP26 climate conference originally scheduled for 2020 was going to be particularly significant.

Then Covid-19 hit, and the conference was postponed to November 2021. But the conference, which will be held in Glasgow, retains its key position in international climate negotiations.

While the urgent crisis of the pandemic has been dominating the headlines, the slower-moving threat of climate change has prompted a wave of activity from governments and businesses. Over the past year, the world’s largest economies have made pledges to reach net zero emissions by 2050 or 2060. Hundreds of companies have made commitments to curb their emissions to align with the goals of the Paris agreement.

The landscape of climate policy and strategy has shifted dramatically in a short space of time. Here are the most important changes:

More countries commit to net zero emissions by mid-century

Modelling published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that to meet the Paris agreement’s more demanding goal of keeping global warming since pre-industrial times to 1.5 °C, global carbon dioxide emissions probably have to hit net zero around 2050. For the less demanding objective of limiting warming to 2 °C, net zero probably has to be reached around 2070. Many of the world’s largest economies have been announcing targets to align with that pathway. The EU, the UK, Japan and South Korea have pledged to aim for net zero in 2050, and the Biden administration has set the same goal for the US. China has announced a target of net zero by 2060.

That might sound like good news in terms of putting the world on track to achieve the Paris goals. But there are two important caveats. First, there are many important countries that have not made any such commitments to net zero, including India, the world’s third-largest emitter, and Russia, the fourth-largest. Other large emitters are still debating their objectives. Indonesia’s government proposed a goal of net zero by 2070, but has not confirmed that and is discussing a more ambitious timetable.

Second, even the countries that have set goals have not yet specified how they plan to achieve them. The EU has been the most detailed in its planning, and it has not yet laid out its strategy for delivering the profound changes that will be required in its energy, transport, construction and other industries. The same is true of other economies with net-zero goals, even when those have been enshrined in legislation.

Countries start to set intermediate targets

One big problem with net zero goals set thirty or forty years in the future is that they create little accountability for today’s leaders, who can expect to be long gone by the time the targets are hit or missed. To address that issue, the UN and other supporters of climate action have been urging governments to set intermediate objectives for 2030.

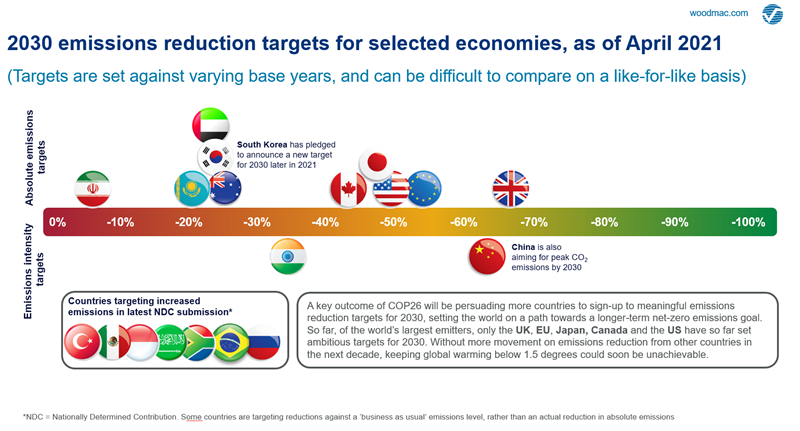

Many economies have responded to that call. This chart shows a selection of the most significant objectives for 2030. Above the line are the goals for absolute reductions in emissions, and below it are the ones framed in terms of emissions intensity.

Even these nearer-term objectives face problems in terms of strategies for implementation, however. The EU’s aim of a reduction of at least 55% from 1990 levels by 2030 implies that in just ten years’ time, almost all new car sales will be EVs, and coal’s share of primary energy will drop to just 6%. EU governments have not yet put in place the policies to deliver those changes, which will be highly controversial in many member states.

In the US, the Biden administration faces a particular set of challenges. The separation of powers between the executive, Congress and the courts, and between federal and state governments, means that the President Joe Biden’s ability to enact his policy agenda is limited. He has set a goal of a 50-52% reduction in emissions by 2030, and wants to pass legislation and introduce regulations to set the US on course to achieving that. Facing an uphill battle in Congress, and an uncertain outlook in the courts, his chances of being able to implement those seem low.

Companies and investors set net zero goals

In parallel to the commitments from governments, hundreds of large international companies have also been pledging to align their emissions with the goals of the Paris agreement. In the autumn of 2019, 60 companies had promised to align their emissions with the more challenging Paris goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. Now there are 589 that have made that commitment, according to the Science-Based Targets initiative. They include Ford, Facebook, Sony, GlaxoSmithKline, General Mills, Volvo, PricewaterhouseCoopers and SSE.

Corporate moves to set objectives for their emissions are increasingly being encouraged by investors. BlackRock in January set out its approach to net zero goals, including a promise to publish the proportion of its assets under management that were aligned to net zero, and asking companies to disclose business plans consistent with the Paris goal of limiting global warming to well below to 2 °C.

In the spring, BlackRock along with other large investors including Vanguard and State Street, joined the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative, which works to support the goal of net zero emissions by 2050. The initiative, launched at the end of last year, now has 73 members with about $32 trillion under management. That is 36% of all the assets under management worldwide.

The members of the initiative have pledged to work with the asset owners who are their clients on decarbonisation goals; to set interim targets for the proportion of their assets under management that are aiming for net zero emissions by 2050, and to ratchet up that proportion every five years until 100% of their assets are aligned with that goal.

That is a colossal amount of capital pushing the corporate sector towards cutting emissions. Corporate buyers of energy are already a significant factor in driving demand for renewable energy. As more of them set net zero objectives, their purchases will become increasingly important.

The agenda for Glasgow

A lot has happened in international climate policy over the past year. The activity from both governments and businesses shows that the transition to lower-carbon energy is accelerating. But the scale of the challenge is still enormous, and at the moment the world is off track for achieving the Paris goals. Over the next five months, and at the talks themselves, advocates for climate action will be doing what they can to persuade more countries and companies to make net zero commitments, and to push those that have made such pledges to put in place strategies for achieving their goals.