Getting serious about tackling global warming

Europe sets the pace for decarbonisation

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

This is the year the world is expected to get serious about decarbonisation. It all comes together in November at COP26 in Glasgow, with governments under pressure to enact legislation to speed up the pace of reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Europe’s ’Fit for 55 package‘, expected this June, could be the template others follow. I chatted to Murray Douglas, Director, European Gas, who critiqued the EU’s challenge in our February Horizons.

Is the market anticipating a harder EU line?

Yes, just look at the carbon price. The EUA (EU Allowance) price is up 30% to an all-time high of EUR44/tonne (US$52/tonne) in the last two months. By 2030, the EU is aiming to cut emissions by 55% compared with 1990, a big uplift from the current target of 40%. The present carbon trading scheme will only deliver about one-third of the emissions reductions required and lets too many carbon-intensive sectors off the hook. A revamp is central to the EU plan.

Carbon price certainty is critical to ensure that the hard-to-abate sectors like steel and cement are fully incentivised to lower emissions. It will also help stimulate investment in nascent technologies such as low-carbon hydrogen and carbon capture and storage that are essential planks of decarbonisation in the longer term.

Traders recognise higher carbon prices are a must for the EU to deliver its goal and are anticipating a tightening of the market. The price will go much higher yet.

Could high-emitting industries exit the EU?

Energy-intensive industries that have been shielded from carbon costs will become liable for the full cost of emissions. The proposed carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) is designed to level the playing field by imposing an equivalent tax on imported goods and avert an exodus of these companies.

How challenging is the EU target?

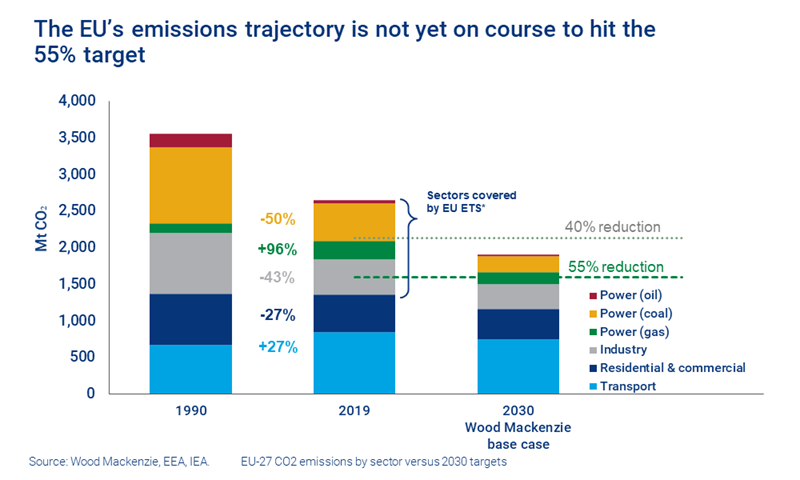

Extremely. The EU has already made great strides, reducing emissions by 25% since 1990. The transition from an industrialised to a service-led economy has helped, but there have been significant policy wins, too. The power sector has been a flagship success, with the emergence of renewables at scale and displacement of much coal fire capacity by gas. Arguably, though, the easy bit’s done. To get to 55% by 2030, the annual rate of reduction has to double – and do so by decarbonising the tougher sectors.

Which sectors are in the crosshairs?

Transport is the big one that can make a difference by 2030. Emissions from transport have actually risen since 1990 and the sector now accounts for about a third of the EU total. Battery electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids are just 13% of light vehicle sales today and need to reach 97% by 2030 – a very tall order, and with the requisite charging infrastructure and power supply to boot.

There’s still much more to do in power – more solar and wind (capacity must double by 2030), more energy storage and less coal. A carbon price of US$65/tonne would deliver the highest level of coal-to-gas switching, cutting emissions by 18% by 2030 compared with our base case, and speed up the phasing out of coal. These will be the main levers to hit the 2030 target.

What’s the EU doing to reduce consumption?

This is absolutely key. The EU has to cut primary energy consumption by 27% over 2019 levels to meet its targets. Buildings alone account for another third of emissions. The ongoing challenge to improve the efficiency of old buildings through insulation is the primary focus; electrification of heating systems can deliver more emissions reductions in time.

Consumer behaviour also needs to change. Consumers will soon face a choice – buy sustainable goods and services or pay more. There’s plenty of scope for subsidies and taxes, including carbon tax, to damp consumer appetite for flying and how people commute.

Where will the money come from?

The investment opportunity in zero- or low-carbon energy is enormous, diverse and, we think, will be a magnet for investors. The EU and its member states have aligned Covid economic stimulus with decarbonisation projects where possible.

Governments will also seek to ‘crowd in’ investment with incentives aimed at attracting private capital. It’s the formula that delivered massive renewables growth, and we fully expect it to hold good as investment shifts down the value chain. The EU wants financing to be focused on the right opportunities – its ‘taxonomy for sustainable activities’ is designed to support the flow of capital into aligned, qualifying activities.

What do other countries think of the EU’s plans?

The EU is in the vanguard. Others can watch the EU shape its policy, its choice of technologies and how it attracts investment. The US has already argued that the CBAM should be a last resort. That’s one example of why COP26 is so important. Global alignment around taxonomy is another, though the difficulties the EU has in getting its own member states to agree on the classification system indicate the bigger challenge.

Glasgow is the opportunity for all countries to talk through each aspect of decarbonisation and emerge aligned with a plan to achieve net zero. We expect wider adoption of interim targets akin to the EU’s Fit for 55 Package – the pace of decarbonisation globally may be much faster this decade than many expect.