How the world gets to a 1.5 °C pathway

And how the conflict in Ukraine changes policy and the energy mix

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Unlocking the potential of white hydrogen

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

The Edge

Are voters turning their backs on the EU’s 2030 climate objectives?

-

The Edge

Artificial intelligence and the future of energy

-

The Edge

A window opens for OPEC+ oil

-

The Edge

Why higher tariffs on Chinese EVs are a double-edged sword

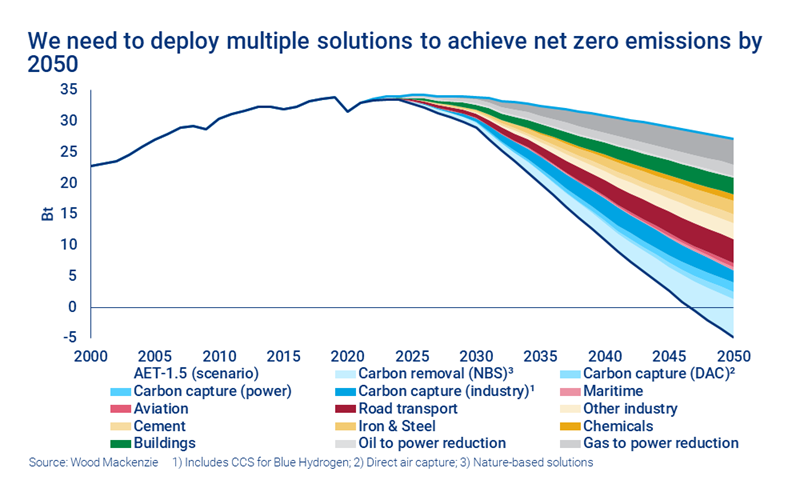

How does the world get onto a 1.5 °C pathway? Our latest accelerated energy transition scenario (AET-1.5), in which the rise in global temperatures since pre-industrial times is limited to 1.5 °C by the end of this century and we reach net zero by 2050, shows the extent of change needed in the energy system to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement. We’ve delved deeper and modelled more sectors and countries in detail to shine a light on the potential for an accelerated decarbonisation. One thing’s clear – it’s going to be quite a challenge.

And that’s before any fall-out from the situation in Ukraine. I asked Prakash Sharma of our Energy Transition Service for his views.

Is a 1.5 °C pathway still feasible?

Always a challenge, it looks even more difficult today than a year ago. The good news is that renewables capacity is being rolled out; the bad news is that the pace lags rampant energy demand growth as the global economy bounces back. The world will have to burn more fossil fuels to bridge the gap so emissions will be higher in the next few years. Consequently, the remaining carbon budget to 2100 will be smaller. We’ll need more CCUS and nature-based solutions to maintain net zero even after 2050.

Does the situation in Ukraine change anything?

It could accelerate decarbonisation. Achieving net zero depends on unity and global cooperation. Governments, companies and wider society have unanimously condemned the conflict. If that same collective will and resolve can be harnessed to tackle climate change, a 1.5 °C pathway might just be achievable.

Does energy security now trump decarbonisation?

It might look that way, but decarbonisation could be the answer for energy security. Big fossil fuel importers will look to diversify their supply of gas, coal and oil away from Russia to other sources. Certainly, Europe will look to alternative sources of piped gas and LNG.

A major shift will be that countries double down on low-carbon energy to bolster energy security. That means more renewables, nuclear and hydrogen. Importers won’t fall into the trap of becoming too dependent on imported fuels – they’ll want a range of suppliers. That’s bullish news for aspiring hydrogen and ammonia exporters in Africa and the Middle East, which could gain at Russia’s expense. Europe has just issued a 10-point action plan that includes removing roadblocks for renewables deployment and importing hydrogen.

Russia itself has huge ambitions in the low-carbon energy space. But its hopes to become a dominant supplier of hydrogen and carbon sinks – CCS and nature-based solutions – look stymied. That’s not just a setback for Russia; it could deprive the world of a potentially significant contributor to the low-carbon future.

What new technologies are coming through?

The accelerated transition is about more low-carbon energy, sooner and faster. The early stages of disruption rely heavily on commercially proven technologies – mainly wind, solar and electric vehicles. Today’s niche technologies will become mainstream later. Long-duration battery storage, nuclear (Small Modular Reactors), geothermal and bioenergy all have a role to play.

Hydrogen/ammonia and CCUS are the big ones. For net zero 2050 to be achieved, both must reach industrial scale, from a tiny starting point today. Promisingly, project pipelines have started to take off. We’ve upgraded forecasts for hydrogen capacity by 20% to 650 MT by 2050 while reducing CCS in markets with limited accessible sequestration capacity. We now think hydrogen and ammonia could be the lower-cost option to decarbonise power and some industrial processes, compared to coal or gas twinned with CCS.

What’s the outlook for fossil fuels?

Pretty resilient for the next 10 to 15 years, natural gas in particular. Governments and investors face a tough balancing act: delivering energy supply to growing economies while at the same time decarbonising the energy system. Even on a 1.5 °C pathway, the world can’t just switch off fossil fuels. We have to wait until the low-carbon alternatives and innovation can deliver.

How will higher energy prices affect progress to 1.5 °C?

The conflict has only fanned the flames. We’re in a commodity upcycle sparked by multiple factors – among them the sharp economic recovery, low investment in supply and uncertainty around the timing of the shift to low-carbon energy.

Energy costs, interest rates and inflation are all rising. To add to the burden, many countries will soon seek to implement carbon pricing or lift prices under existing regimes so they can incentivise investment in low-carbon technology. Carbon prices rise to a global average of US$175/t by 2050 in AET-1.5 to deliver the necessary emissions reductions from hard-to-abate sectors.

High prices will make it harder for policymakers to get the ball rolling on decarbonisation this decade, and bolstering energy security and progressing towards net zero could mean higher prices for longer. But it’s preferable to the high prices and low energy security we have now.

How will the 1.5 °C pathway be financed?

Getting to net zero by 2050 will cost around US$60 trillion on our estimates, spread over the three decades to 2050 across power, mining and metals, hydrogen, CCS and oil and gas. Governments will look to ‘crowd in investment’ for low-carbon technologies – the EU taxonomy and US 45Q tax relief are among a growing list of incentives.

The conflict will only serve to reinforce financial institutions’ and banks inclination to invest in economies that are stable, respect the rule of law and have an action plan to get to net zero by 2050.