Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Demanding new emissions goals set course for low-carbon future

At a US-hosted climate summit this week, large economies discussed their ambitious objectives for cutting emissions. Now comes the hard part.

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

-

Opinion

What the conflict between Israel and Iran means for energy

The central tension at the heart of the Paris agreement on climate change, adopted in 2015, was the gap between the shared commitment to limit global warming to “well below” 2° C, and the emissions cuts that individual countries pledged to meet that objective. It was easy to see that even if every country met its goal, known as a Nationally Determined Contribution, total global emissions would still push warming well above 2° C.

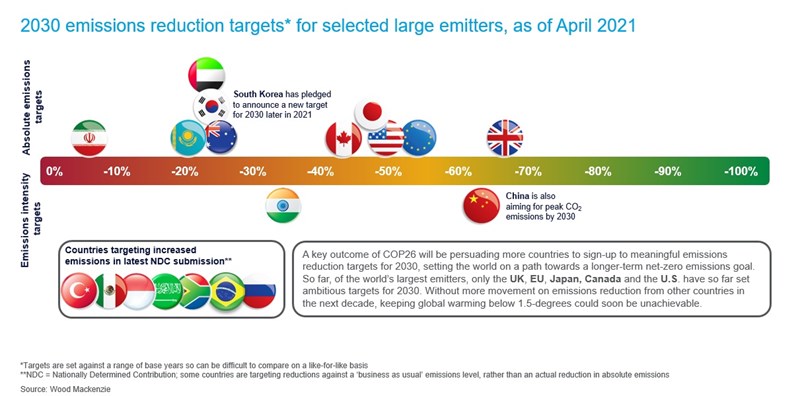

The agreement had a solution to that problem: countries have agreed to publish a new NDC every five years, committing to deeper emissions cuts than the one before. It is often described as a ratchet of escalating ambition, operating on a five-year cycle. This year countries are supposed to complete the first round of new NDCs, which will be reviewed and discussed at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in November. This week, we have seen some of the world’s largest economies fulfill that obligation, announcing demanding new targets for cutting emissions. The focus is now going to shift away from setting those goals and on to the question of whether they can be achieved.

In the past few days there has been a flurry of announcements of new emissions goals, from the EU, the UK and Canada, among others. President Joe Biden, who has been hosting an online climate summit on Thursday and Friday, set a new goal for the US to cut its emissions by 50-52% from a 2005 baseline by 2030.

That target is challenging in the extreme. The new US NDC, as filed with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, is light on detail about how the proposed cut in emissions can be delivered. It suggests that the power generation industry faces the most radical changes, as a result of the administration’s goal of net zero emissions for the sector by 2035, but the rest of the economy will also be called on to deliver significant reductions.

Wood Mackenzie analysts will have more detailed evaluations in the days and weeks to come, but for a start it is worth thinking about the rate of decline. Over the 14 years 2005-19, total US greenhouse gas emissions, net of carbon sinks such as forests and grassland, dropped by 13%. Over the 11 years to 2030, they are supposed to drop by a further 37% of that 2005 baseline. Canada, which has repeatedly failed to hit its objectives for emissions reductions, is a reminder that setting the goal is the easy part.

Even so, the fact that many leading countries and economies are now setting goals to be achieved over the next decade is an important indicator of the growing international momentum behind climate action. Objectives to be achieved by 2050 are important in terms of setting strategic direction, but just about everyone who is leading a government at the moment will expect to be enjoying a comfortable retirement by then. Targets for 2030 are much more likely to be used to judge the success or failure of heads of government and their teams, who will be hoping to still be in power at that point. As this chart shows, the number of countries and economies setting these medium-term objectives is growing fast.

The rush of new emissions goals gave a fillip to the first day of the climate summit, held on Earth Day, and there were warm words and promises of action from the world leaders who logged in. That was true even for some unexpected figures. President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, who a few years ago had talked about withdrawing from the Paris agreement, pledged that his country would reach emissions neutrality by 2050.

However, the leaders also inevitably pursued their own national agendas. That was true of the host, President Biden, who focused much of his statement on his hopes that the transition to low-carbon energy will boost the US economy and create millions of good jobs. “When people talk about climate, I think jobs,” he said. “The countries that take decisive action now to create the industries of the future will be the ones that reap the economic benefits of the clean energy boom that’s coming.” There was some important support for that approach this week from the United Mine Workers of America union, which represents coalminers. It said it would support the Biden administration’s climate policies if they were backed by a commitment to a “real energy transition”, including support for coalmining communities and good jobs in low-carbon industries.

President Xi Jinping of China also addressed national concerns in his video address, telling rich countries they needed to do more to help developing countries strengthen their resilience against climate change, and urging them to “refrain from creating green trade barriers” such as carbon tariffs. He did not raise the ambition of China’s previously announced emissions goals: a peak by 2030 and net zero by 2060. He pointed out that the period between peak emissions and net zero was expected to be significantly shorter for China than for many developed countries, and said the goal “requires extraordinarily hard efforts from China”, an assessment that is broadly shared by Wood Mackenzie’s analysts.

Two of the most interesting points from the day came in remarks by John Kerry, President Biden’s special envoy for climate. His first concerned the durability of US climate policy. Given the finely-balanced split of the parties in Congress, it will be difficult to pass legislation to implement much of the policy agenda needed to achieve the emissions cuts pledged in the NDC. The Biden administration says it can do a lot, including the move towards a zero-emissions power sector through regulation and executive action rather than legislation. But that strategy will be challenged in the courts and could be undone relatively quickly by the next Republican president.

Kerry suggested the key to sustaining emissions reductions through successive changes in administration was getting the private sector to buy into that agenda. “No politician in the future is going to undo this because, all over the world, trillions of dollars, trillions of yen, trillions of euros are going to be heading into this new marketplace [for low-carbon energy],” he said. He added, on the transition to electric vehicles: “No politician, no matter how demagogic or how potent and capable they are, is going to be able to change what that market is doing.”

His other important observation was about the technologies that will be needed to stabilise global temperatures. Even if the world does manage to reach net zero emissions by around 2050, the greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere mean the globe will continue to warm. To limit that impact, “we still need to get carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere”, Kerry said. There are plenty of proposals for negative emissions technologies that are being looked at, and some are well advanced. Unlike solar and wind power, or EVs, Direct Air Capture of carbon dioxide is unlikely to appeal to the private sector at a large scale. The amount of carbon dioxide that would need to be removed from the atmosphere to offset human emissions is much greater than the amount we currently have uses for. Putting a hefty price on carbon looks like the only way to make DAC commercially viable, and that is something that only a government can do.

ExxonMobil proposes carbon capture cluster

One clear sign of the growing focus on climate change among investors, governments and customers is the way that US oil and gas companies have been developing increasingly detailed plans and ideas for cutting emissions. There was a good example of that from ExxonMobil this week: a “Texas-sized” plan for carbon capture and storage. It is a very interesting idea that addresses some of the critical problems that have held CCS back in the past. It would require extensive government involvement, but given that carbon capture seems essential for any realistic plan for meeting the Paris agreement goals, it is worth a serious look.

There are, of course, plenty of carbon capture projects already in operation around the world, with about 20 more under development in the US alone. Their economics have often proved difficult to sustain, however, as in the case of the Petra Nova project in Texas, which was shut down last year after low crude prices meant that its use of captured carbon dioxide for enhanced oil recovery became unviable. Total global carbon capture capacity of about 47 million tons of carbon dioxide per year is far short of the billions of tons per year that we think will be needed to achieve the Paris goals.

ExxonMobil’s proposal is intended to “dramatically accelerate” the progress of CCS. It would create a multi-user hub on Houston’s Ship Canal, which can collect carbon dioxide from all the petrochemical, manufacturing and power generation facilities in the area and pump it into storage under the Gulf of Mexico. By 2030, it could be capturing 50 million tons of carbon dioxide per year, which is more than all the CCS projects currently in operation worldwide. By 2040, it could be capturing 100 million tons a year.

The plan could be a “game changer” for the deployment of CCS, Joe Blommaert, president of ExxonMobil Low Carbon Solutions, wrote in a blog post. “Lessons learned from this Houston CCS Innovation Zone could be replicated in other areas of the country where there are similar concentrations of industrial facilities located near suitable CO2 storage sites, such as in the Midwest or elsewhere along the US Gulf coast,” he added.

The catch, inevitably, is the cost. Blommaert acknowledged that the Houston CCS hub would be a “huge” project, needing investment of $100 billion or more from the private and public sectors. The economics will work only with extensive government funding, probably including a price on carbon to reward the companies that sequester it. The regulatory and legal issues raised are also complex, and the project will need a framework that encourages investment and cooperation among federal, state and local officials.

Still, support for CCS is one of the few climate policies that can win bipartisan support. There are two new bills in Congress that would bolster government funding for carbon capture projects and infrastructure, and both have Democratic and Republican backers. The most recent would make the existing 45Q tax credits for CCS significantly more generous, with a maximum value of $120 per ton of carbon dioxide sequestered, up from $50 per ton currently. It would also make them available for an additional five years, to the end of 2030. The other bill would create new government support for commercial CCS infrastructure and storage hubs, exactly the kind of project ExxonMobil is proposing.

And even if the Houston Ship Channel hub does not go ahead, the idea is well worth further investigation. As Blommaert says, there are other locations in the US and around the world that have the critical combination of a concentration of large industrial emission sources and proximity to geological formations that can store large amounts of carbon dioxide. The size of the market has been critical for wind and solar power, allowing the technology to benefit from economies of scale. The hub approach offers a chance to achieve the benefits of scale in CCS, potentially bringing its costs down to levels that will be politically acceptable. It may offer the CCS industry its best hope of making the breakthrough it needs, and that the world needs if the vision of the Paris agreement is to be made a reality.

In brief

The European Commission has provisionally decided to include nuclear power in its taxonomy of sustainable activities, much to the relief of the industry. The taxonomy is expected to be critical in determining access to capital for European industries. Investors will use it for investment decisions and when selling financial products, and capital will be directed towards companies and industries classified as sustainable.

Meanwhile, natural gas has been left out of the EU taxonomy for the time being. The argument over the sustainability of gas has been heated on both sides, and the Commission has decided to look at the issue separately. It will be assessing the role of gas in the energy transition and will make a decision on how it should be classified after the review process is completed over the summer. The BDEW, the German utility industry group, has warned that the delay “puts important energy transition investments at risk”. It argues that Germany needs investment in new gas-fired generation capacity to replace coal and nuclear plants that are shutting down.

Bye Aerospace hopes it will have the first aircraft designed for electric propulsion to win certification from the Federal Aviation Administration. It is hoping the eFlyer2, a low-cost two-seat training aircraft, will be granted its safety approval by the end of 2022. The company is also developing the eFlyer 899, an eight-seater electric aircraft, which it aims to have on the market by 2026.

Greta Thunberg, the Swedish climate activist, has given evidence to a committee of the US House of Representatives that is looking into “fossil fuel subsidies”.

Talks over the US re-entering the international deal on Iran’s nuclear programme have made progress, including setting up another working group of experts, an EU diplomat has said. If the talks are successful and the US is persuaded that Iran is doing enough to confirm that it is not walking towards building nuclear weapons, it could lead to a relaxation of sanctions and an increase in Iranian oil exports.

US Steel is the latest company to have set a goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2050. The announcement is significant because steel is one of the industries in which achieving deep cuts in emissions is particularly difficult. US Steel says it plans to achieve its objective by using electric arc furnaces with zero-carbon power sources, combined with other technologies including direct reduced iron and carbon capture.

And finally: in a week where people have been debating the future of our planet, some inspiring news from a different one. On Monday the Ingenuity helicopter took the first ever powered flight on Mars. It has been just 117 years since the Wright brothers took the first heavier-than-air flight on earth. Now NASA is able to launch an autonomous flying vehicle 173 million miles away, on a planet with only about 1% of the surface air pressure of earth. From an energy point of view, the helicopter confirms the critical importance of photovoltaic solar power for operations in remote and challenging locations. The Ingenuity is powered by a lithium ion battery, charged by a solar panel above its rotors. The battery allows for about 90 seconds of flying time each day, based on power consumption of about 350 Watts when the Ingenuity is airborne.

Other views

Prashant Khorana — Investing in the energy transition

Le Xu — Tracking the trajectory of the global energy storage market

Gavin Thompson — How Asia changed the global LNG market in the space of a year

Julian Kettle — Tin: the forgotten foot soldier of the energy transition

Vijaya Ramachandran — Blanket bans on fossil-fuel funds will entrench poverty

Laura Myllyvirta — Sino-US competition is good for climate change efforts

Simon Lewis — Fossil fuel pressure and risks mounting for multilateral development banks

Robinson Meyer — An outdated idea is still shaping climate policy

Jason Crawford — Why has nuclear power been a flop?

David Sheppard and Nathalie Thomas — Scotland faces up to life after oil

Quote of the week

“If you really want to stop Russian aggression against Ukraine, you have to stop Nord Stream 2. As simple as that.” — Donald Tusk, the Polish politician who is a former president of the European Council and now president of the European People’s Party, linked the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project to the build-up of Russian forces on the border with Ukraine.

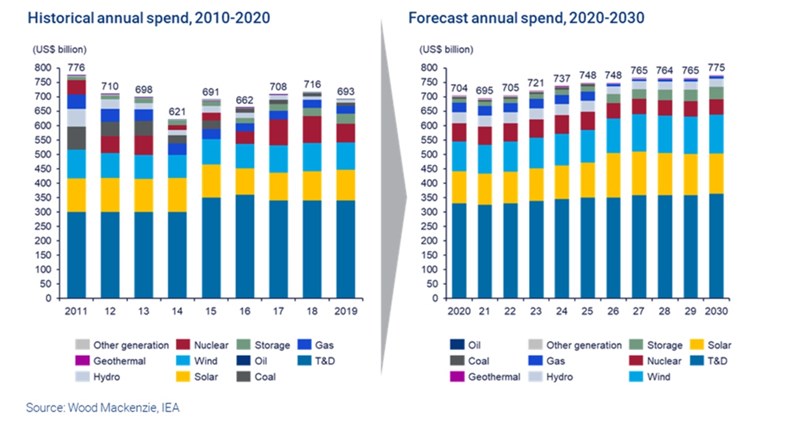

Chart of the week

This comes from a timely report in this week of the climate summit and new emissions pledges. Written by Prashant Khorana, Wood Mackenzie’s director of power and renewables consulting, it sets out six capital allocation principles for power and renewables investors. This chart sets the scene by showing our forecasts for expected investment in the power industry over the coming decade, broken down by sector. One clear message is how important investment in transmission and distribution infrastructure is; another is how wind and solar dominate investment in generation. Another key point: investment in gas-fired generation, already a small percentage of the total, dwindles away to almost nothing by 2030. Storage, meanwhile, grows rapidly.