Get this complimentary article series in your inbox

2 minute read

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Latest articles by Julian

-

Opinion

Metals investment: the darkest hour is just before the dawn

-

Opinion

Ebook | How can the Super Region enable the energy transition?

-

The Edge

Can battery innovation accelerate the energy transition?

-

Featured

Have miners missed the boat to invest and get ahead of the energy transition?

-

Featured

Why the energy transition will be powered by metals

-

Featured

Could Big Energy and miners join forces to deliver a faster transition?

As Oscar Wilde once said: “There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about and that is not being talked about”. On that basis, a quick review of mainstream, commercial and even academic coverage of the energy transition suggests tin is badly in need of a new agent. In fact, one could be forgiven for thinking the only metals that matter to the energy transition mission are lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, rare-earth elements and perhaps aluminium. The fact that tin isn’t being talked about much should not only be a surprise but also a concern.

So, what’s driving demand for tin? And could a lack of ESG-compliant supply affect the pace of the energy transition?

Dispelling tin myths

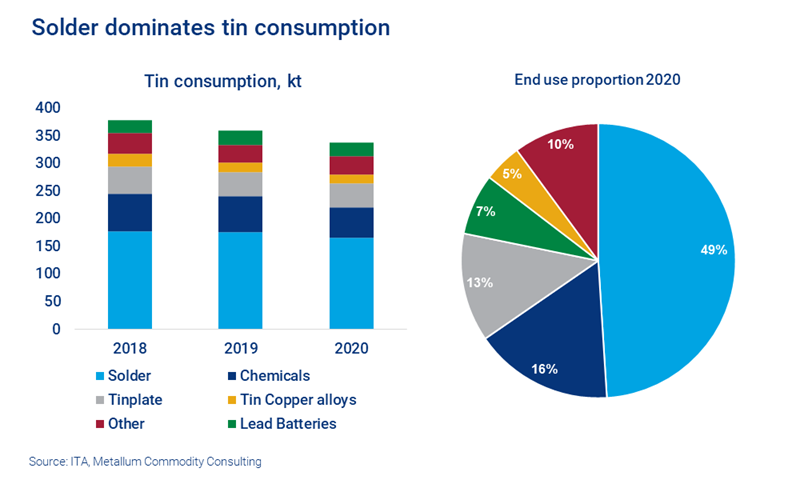

Before we go further, it may be useful to dispel some commonly held assumptions about tin. The use of tin coating to provide corrosion resistance to iron and steel fabricated parts dates back to the 1600s. ‘Tinplate’ – sheet steel or iron coated with tin – is now primarily used in the food and beverage industry, and is why we refer to ‘tin cans’ or ‘tins'. However, plating uses, once dominant, now account for just 12-13% of total consumption, behind chemical use (15-18%).

The major use for tin today is actually in solder to create electrical connections. Currently, this alone accounts for close to 50% of demand.

What’s so special about tin?

Tin connects the electrical and electronic world, and it is this use in typically small-scale electronic components that makes the metal critical to the energy transition. Put simply, every component of the low-carbon and increasingly data-driven economy requires tin: without it electrons don’t flow – which means mobile phones don’t work, electric vehicle batteries don’t charge, and the Internet of Things ceases to exist.

While other metals can theoretically be used for this purpose, given the abundance and effectiveness of tin there really is no economic substitute.

What will drive increased demand?

The energy transition is the biggest long-term demand driver of tin. As this is in effect a switch from energy delivered via a pipe to energy delivered via a cable it will require increasing volumes of tin to join it all up. This will be supported in the medium term by the adoption of 5G networks and the Internet of Things. Beyond that, there’s potential for tin to be added to silicon in the graphite used in the anodes of lithium-ion batteries to slow degradation. And finally, tin is also cited as offering strong potential in combination with other metals for cathodes in both ‘wet’ battery technologies and solid-state batteries.

Moves to eliminate the other major constituent of solder, lead, are likely to create even higher demand for tin. The EU Restriction of Hazardous Substances (“RoHS”) directive already limits the lead content in electronic goods to below 1000ppm and requires its elimination in solder by 2030. Similar regulations have been passed in China, Japan and Korea, and while no regulations yet exist at a national level in the US, several individual states do restrict the use of lead in certain products.

A global alignment to the 2030 EU standard could add a further 20 kilotonnes per year (kt/a) to demand by 2030. But even before such legislation, electronics manufacturers are already voting with their feet in adopting lead-free solders.

A metal not given the recognition it deserves

Of course, tin is one of a raft of metals integral to delivering a low-carbon world. The critical minerals list recently published by the Canadian government followed in the footsteps of the EU, US, Japan and India by citing tin among 31 critical metals. However, the US quotes tin as primarily used in the coating of steel. India characterises the metal as of low economic importance and low supply risk, and the EU fails to cite tin as a ‘critical' metal at all. This suggests the lens through which India and the EU in particular are looking at tin is one that focuses on the potential quantity of supply, as opposed to the risks surrounding that supply.

Supply potential is high — but so is supply risk

It’s important to note that while there is no shortage of existing and potential tin supply, that supply could come with environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk.

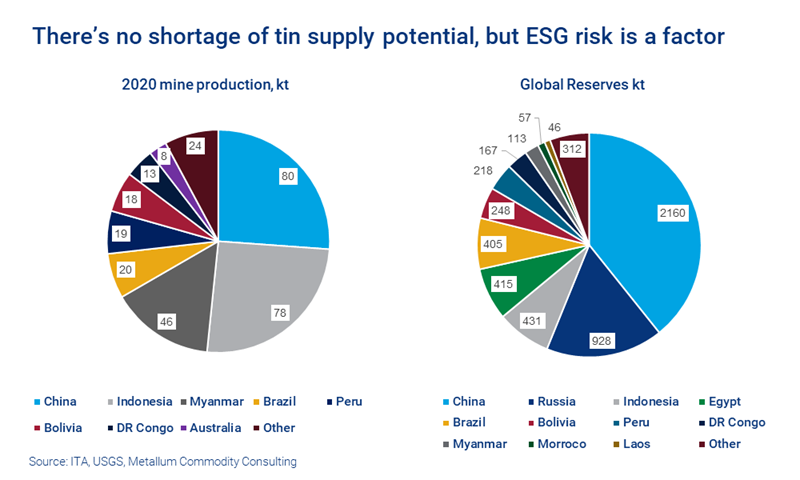

Most tin production comes from countries that, according to Verisk Maplecroft, have high ESG risk. As the chart below shows, China, and Indonesia together account for over 50% of mine supply, while Myanmar is currently the third-largest supplier, and production in the DRC is rising quickly.

If the high level of ESG risk associated with current tin mining is a concern, looking at potential supply based on reserves brings no comfort. Based on current consumption rates, existing global reserves of 5500 kt represent around 18 years of mine requirement. However, based on Verisk Maplecroft’s quantitative risk analysis, some 90% of these reserves are also located where ESG risk is high. With consumers and investors becoming extremely focused on ESG-compliant sourcing, there could be serious issues surrounding tin.

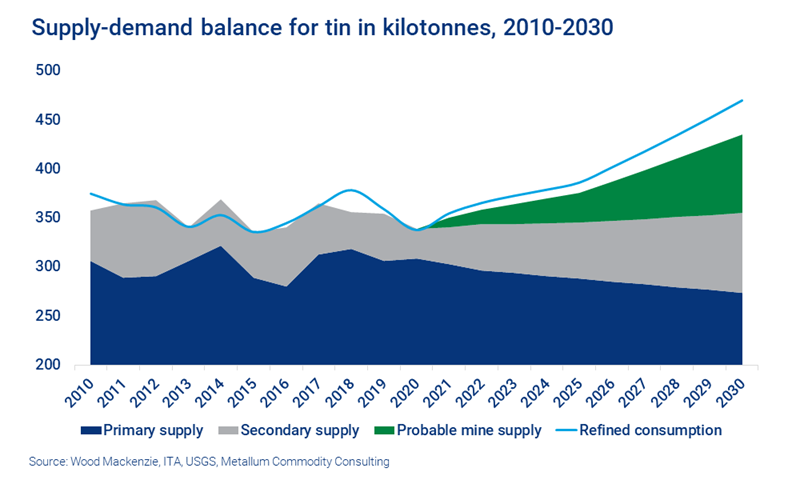

So, could secondary sources fill some of the supply requirement? Metallum Consulting estimates that, due to the pandemic, supply from secondary sources dropped by 20 kt year-on-year to 30 kt in 2020. The company forecasts secondary supply could reach its previous peak of 60 kt by 2025. We expect that, assuming policy drives greater recycling, this could rise to 80 kt by 2030. Volume recovery of external tin scrap is, however, problematic as the vast majority of electronic waste currently ends up in landfill.

Why a tight market could just get tighter

Aside from the risks, the level of supply is already an issue, with the tin market running a deficit for all bar one of the last five years. While there is some potential for non-base case additional mine supply to be brought on stream, we believe elasticity of supply is limited to around 80 kt/a by 2030. This is set against base case mine supply which will fall by around 1% per year due to grade decline or reserve depletion.

As a result, even with ongoing demand growth of just 3.5% per year over the current decade and rising secondary recovery, the tin market is set to remain tight for the foreseeable future. It is highly unlikely any significant boost to tin demand from an accelerated energy transition could therefore be met by projected supply, much less from ESG-compliant sources.

The fact that the major diversified miners are totally absent from tin mining only adds to concerns regarding long-term supply development, particularly as resources need to be converted to reserves, and indeed developed, at a rate hitherto unseen. Price will obviously be an important driver of resource/reserve conversion, especially as historic tin demand has proved sensitive to any sustained period of prices above the industry’s incentive price. Metallum estimates that the current incentive price for major project development is in the region of US$21,000/t, some way below current price levels, although ESG compliance will of course also be a major determining factor.

The threat to the energy transition

For tin to have maintained a key economic function since the Bronze Age shows it is a metal with great adaptability. Its alloying, coating and conductive properties will continue to ensure it has a role of key importance in a low-carbon world. Indeed, its use in electronics has the potential to make it a kingmaker in terms of the energy transition.

However, the issues of ESG risk and limited projected supply associated with tin mining, coupled with the challenge of tin recovery from the waste stream, mean that demand could significantly outstrip supply. To quote Samuel Coleridge Taylor’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, tin threatens to become a case of “water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink”.

Get unique insights on metals and mining in your inbox

This article is part of a regular complimentary series exploring opportunities and challenges in the world of metals and mining. Fill in the form at the top of the page to make sure you hear about new articles in the series as they are published.