Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

US gasoline prices hit record highs

Refining capacity constraints, OPEC+ strategy and investor demands have driven up fuel prices worldwide, with little prospect of relief in the short term

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

-

Opinion

What the conflict between Israel and Iran means for energy

John Kennedy, a Republican senator for Louisiana, this week used a vivid image to highlight concerns about gasoline prices. “In my state, the price of gas is so high that it would be cheaper to buy cocaine and just run everywhere,” he joked on Fox News. While both financially and physiologically questionable, his remark did capture the widespread alarm felt by Americans about the cost of fuel. The average retail price of gasoline in the US this week hit a new record high of $4.977 a gallon, according to the Energy Information Administration.

Even in real terms, adjusting for consumer price inflation, retail gasoline prices are close to all-time highs. The average US gasoline price peaked at the equivalent of a little over $5.50 in today’s money in June and July 2008. That peak was soon followed by a plunge into the worst recession since World War Two. Fuel costs were far from the only cause of the slump: excessive household debt, the widespread use of poorly-understood derivative instruments throughout the financial system, and the bursting of the house price bubble also played key roles. But fuel prices at these levels are an ominous sign for the US economy.

They are also a dire indicator for President Joe Biden and other Democrats looking ahead to the midterm elections in November. A recent poll from Morning Consult / Politico found only 39% of respondents approved of the president’s job performance, while 58% disapproved, and rising gasoline prices and the cost of living more generally seem to be significant factors in that. A Gallup poll in April found 6% of respondents cited fuel and oil prices as one of the most important problems facing the US, up from just 1% in February, with 17% citing the high cost of living and inflation in general. The bad news for the Democrats is that the upward pressures on gasoline prices are unlikely to have eased significantly by the time November comes.

Gasoline prices are high today because of a combination of strong crude prices — Brent has been trading this week in a range of around $120-$125 a barrel — and refining margins that have blown out to record levels. Despite the impact of lockdowns in China to control the spread of Covid-19, global demand for oil products is still on the road to recovery. It is on course to be 3% higher this year than in 2021, and to exceed pre-pandemic highs by the second half of next year.

The supply response has been damped by a range of factors including the strategy of the OPEC+ countries, investor pressure on E&Ps to return capital, and a shortage of refining capacity. The international response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also helped to drive prices higher for both crude and refined products. New sanctions, boycotts by US and European buyers, and the EU’s plan to stop most imports of Russian oil by the end of the year, have stoked fears that Russian exports, which have so far remained reasonably robust, could be curtailed more sharply in the future.

Upstream, the OPEC+ countries have continued to unwind their pandemic response production cuts at a measured pace. There was a slight acceleration announced last week: the group’s ministers increased their agreed production limit by 648,000 barrels per day for July, bringing forward part of the increase originally scheduled for September, rather than the 432,000 b/d increase announced for recent months. However, OPEC members have in total been producing about 920,000 b/d less than their agreed target, principally because of shortfalls from Angola and Nigeria.

In the US, meanwhile, production growth remains muted for the time being, constrained by supply chain issues and E&Ps’ general preference for using high prices to reward investors rather than increase capex budgets. Wood Mackenzie expects US crude production to increase by 570,000 b/d in 2022, which is well below the pace of growth seen in the boom years of the early 2010s.

Downstream, the issues are even more stark. About 3 million b/d of refining capacity worldwide was shut down during the pandemic, and the new capacity being built to replace it is mostly not yet available. Refining margins have soared to record levels, as the global industry struggles to meet demand. China has meanwhile moved to restrict exports of refined products, which are currently running at about half last year’s levels, further tightening world markets.

Product inventories are low in many key demand centres including the US east coast and Europe, making prices volatile. Alan Gelder, Wood Mackenzie’s vice-president for refining, chemicals and oil markets, says the industry has been playing a game of whack-a-mole, shifting refinery yields to maximise output of whichever product has the most favourable pricing. But overall, global markets for transport fuels will remain tight, unless either significant new refining capacity comes on stream, or demand falls, or both.

Three large refining projects, Jazan in Saudi Arabia, Al-Zour in Kuwait, and the Dangote Petroleum Refinery in Nigeria, are in the process of completion and start-up, promising to ease supply constraints. Jazan is ramping up production, Al-Zour is projected to start up next month, and the Dangote refinery is expected to come online early next year. Jazan and Al-Zour are configured for producing predominantly middle distillates, and as they come on stream they will ease some of the tightness in the global diesel market, allowing North American and European refiners to shift to producing more gasoline.

Starting up a new refinery is a complex and delicate process, however, and unexpected delays are always possible. The only sure-fire way to ease market tightness and bring gasoline prices down would be a recession. That is not the current consensus expectation of US forecasters, for this year or next. But the longer fuel prices remain at levels that cause financial strain and damage consumer confidence, the greater the risk of a downturn will become.

High prices are hitting fuel demand, but are not yet driving a mass shift to EVs

Another US senator discussing fuel prices this week was Debbie Stabenow, from Michigan, who at a Senate finance committee hearing sang the praises of her electric car. “I got it and drove it from Michigan to here just last weekend and went by every single gas station — it didn’t matter how high it was — and so I’m looking forward to the opportunity for us to move to vehicles that aren’t going be dependent on the whims of the oil companies and the international market,” she said.

Her comments were attacked by Republicans as elitist, on the grounds that many people cannot afford an EV. The perception that electric vehicles are much more expensive than their internal combustion engine equivalents might be misleading, but it is certainly true that trying to buy an EV at the moment can be frustrating. Prices for Teslas and some other marques have been rising because of increased raw material costs, and the vehicles are often unavailable. Waiting times for EVs have been stretching out, to more than a year for some models, in part because of production delays caused by semiconductor shortages.

US consumers bought more than 17 million cars and light trucks every year between 2015-19. This year, they are likely to buy only 13-14 million. The market share for EVs and plug-in hybrids is rising fast, but is still expected to be only about 7% this year. Record high gasoline prices have certainly stoked consumer interest in EVs, but they are not triggering a sudden transformation of the US vehicle fleet.

The immediate impact on fuel demand comes from drivers changing their behaviour. Darren Rebelez, chief executive of Casey’s General Stores, the convenience store chain, noted on a call with analysts this week that in its locations with gasoline prices in the top quartile, “ we are starting to see some erosion in volume in the low single digits”. Across the company, volume growth was still 0-2%, he said. But he added: “Six dollars a gallon is uncharted water for everybody. So I’m not sure what to expect at that, but I would imagine there is some demand destruction at that point.”

Suzanne Danforth, Wood Mackenzie’s director for Americas downstream oil, says the signs of high prices chipping away at US fuel demand can already be seen in the data. The US used 9m b/d of gasoline in the four weeks to June 3, about 1% less than in the equivalent period of 2021, even though Covid-related regulations across the country are generally much less restrictive now than they were then. “Gasoline demand is trending slightly below last year’s summer driving season, and there is definitely some downside risk,” Danforth says. “In our base case forecast, US gasoline demand peaked in 2018, but it is broadly flat for the next few years. The downside case is what happens if there is a recession.”

In brief

An explosion at the Freeport LNG plant in Texas on Wednesday will cut US LNG exports significantly, at least until the end of the month and possibly for longer. All three trains at the plant were shut down, and the company said it would remain offline for a minimum of three weeks. Most of Freeport’s cargoes had been heading to Europe, helping to reduce reliance on Russian gas. The shutdown takes about 1.3 million tons of LNG a month off the world market, putting upward pressure on gas prices around the world.

When news broke about the explosion at Freeport, US natural gas prices initially fell sharply. Benchmark Henry Hub futures, which had been trading at about $9.40 per million British Thermal Units, their highest level since 2008, dropped on Wednesday afternoon to $8.20 per mmBTU. The respite from rising prices was short-lived, however. A heatwave has been hitting Texas and much of the southern US, driving up demand for electricity for cooling. The National Weather Service warned that in the Fort Worth / Dallas area, for example, “conditions will be uncomfortably and at times dangerously hot across the region over the weekend, with afternoon highs topping 100 [°F] across most of the area.” By the end of the week, front-month Henry Hub futures were back around $9 / mmBTU.

The Biden administration is seeking to use its powers under the 1950 Defense Production Act to boost supplies of key equipment for low-carbon energy. The Department of Energy has been given the authority to accelerate domestic production of solar equipment, transformers and electric grid components, heat pumps, insulation, electrolysers and platinum group metals for making green hydrogen, and fuel cells. Jennifer Granholm, the energy secretary, said invoking the act was a way for the US to “take ownership of its clean energy independence.” She added: “For too long the nation’s clean energy supply chain has been over-reliant on foreign sources and adversarial nations. With the new DPA authority, DOE can help strengthen domestic solar, heat pump and grid manufacturing industries while fortifying America’s economic security and creating good-paying jobs, and lowering utility costs along the way.”

At the same time, the administration announced another move that is likely to have a greater immediate impact: it invoked emergency authority to suspend for up to two years any additional duties on solar cells and modules imported from Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia. Imports from those countries are currently being investigated by the Department of Commerce over alleged dumping, a process that could lead to a round of steep new duties being imposed. The mere fact of the investigation being launched, even before its conclusions are in, has caused great uncertainty and disruption, leading to many projects being delayed or canceled. The Solar Energy Industries Association has warned that it is having a devastating impact on the industry.

Michelle Davis, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for solar, said the delay in the duties would bring some short-term relief to the industry. As a result of the dumping investigation, Wood Mackenzie analysts cut their forecast for US solar installations this year from 21.9 gigawatts to 15.6 GW, a 29% reduction. The delay in imposing new import duties should make it possible to write some of that capacity back into the forecast. Davis said the change was “expected to create approximately 2-3 GW of upside potential.”

Other views

Julian Kettle — Does the energy transition start and finish with metals?

Sushant Gupta — From grey and brown to green and blue: low-carbon hydrogen in refining

Michelle Davis — Anticircumvention investigation paralyses US solar

US Solar Industry Sees Worst Quarter Since 2020

US commercial solar project acquisitions see dramatic price variation over 2018-2021

Quote of the week

“The cause of this war, the enabler of this war is from oil and gas. So this is the point for everybody: just to think about this, and use this opportunity to stop [funding] the war and to stop [using] so much energy, and think about our way of life."— Svitlana Krakovska, a leading Ukrainian climate scientist, said in a BBC interview that climate change was not a priority for her country right now, but urged others to step up their efforts to shift away from fossil fuels, to reduce their reliance on Russian energy.

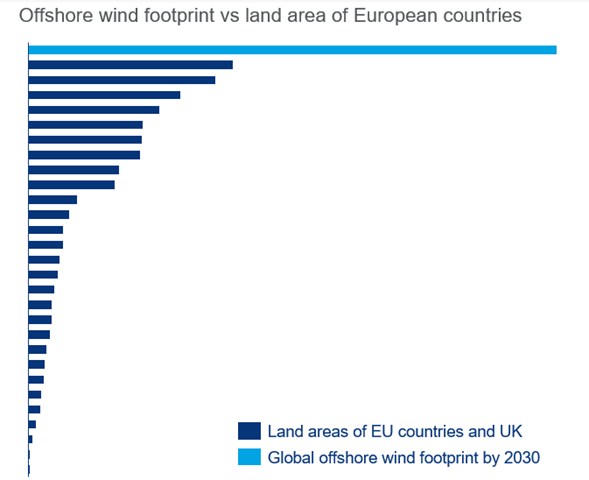

Chart of the week

This comes from Wood Mackenzie’s recent Horizons report on the changing conditions for success in the offshore wind industry. It looks at expectations for the size of the industry, not in terms of investment or generation capacity, but in terms of area covered by the footprint of offshore wind farms. As you can see, that is set to be a very significant area: more than twice the size of France, the largest EU member. As the authors Søren Lassen and Chris Seiple point out, the new parameters that are increasingly coming into use in offshore wind tenders will be key to optimising such expansive use of the seas.