Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Wham, bam, CBAM

Europe’s plan to take carbon prices global

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Europe’s carbon market is poised for the most radical changes in its 17-year existence. The European Commission (EC) plans to introduce the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which could be a first step towards a global carbon market. This week, after two years of discussion and close to the end of the legislative process, a more ambitious proposal failed to gain support in its present form in the European Parliament. Our carbon markets experts, Nuomin Han (Senior Analyst) and Elena Belletti (Head of Carbon Research) analysed the CBAM. I asked them what it all means.

Why were the proposals voted down?

Political expediency. Politicians are wary of heaping unnecessary pressure on industry and consumers who are already struggling to cope with extremely high energy prices. We think it’s a temporary setback and the proposals, likely with amendments and including CBAM, will go through in due course. The EU’s aspiration to push harder towards net zero is still there, it’s really a question of pace and timing.

What is the EU trying to achieve?

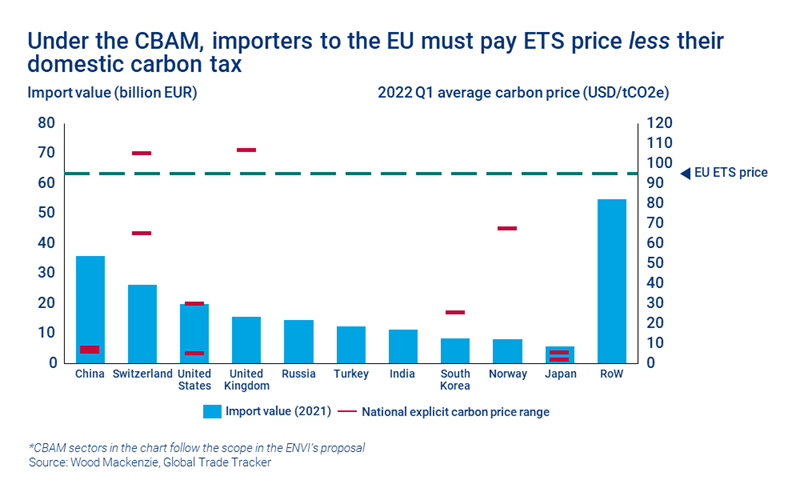

Broadly two things – to tighten the emissions trading system and introduce the CBAM. Europe already has the most sophisticated carbon market and highest carbon prices in the world – the EU ETS price is currently EUR85/tonne (US$90/tonne).

The proposals for the ETS were mainly focused on two things. First, increasing the target for emissions reductions to 67% by 2030, compared with the 61% currently in the Fit-for-55 proposal by the European Commission. Secondly, to taper to zero by 2030 rather than 2035 the ‘free allocations’ of certificates that cushion certain sectors from the full cost of ETS certificates. These reforms are essentially precursors to enable an effective CBAM.

What happens next?

We’d expect pragmatic solutions with, say, an emissions reduction target of 63% by 2030; and free allowances tapering to zero by 2032. The Parliament will hold an exceptional session on 22-23 June and vote again on the ETS and CBAM packages, but the timetable for the vote and subsequent implementation in 2023 is getting tight.

Why is carbon pricing important?

Carbon markets will play a critical role in the energy transition. Many countries already tax carbon but the average price of US$25/tonne globally is too low to incentivise the emissions reductions needed to achieve net zero by 2050.

Why is CBAM such a big deal?

It could be the first step towards global carbon pricing because it externalises the EU’s carbon market. The EU effectively will impose its ETS carbon price on goods imported to the EU, equalising the carbon costs of EU and non-EU products. It’s designed to stop carbon leakage – such as EU producers relocating elsewhere – and to ensure European industries can stay competitive globally.

Importers of goods to the EU can ‘net off’ any domestic carbon costs against the ETS price. All importers, though, will incur additional administration costs, which will include calculating and reporting the embedded emissions and costs of purchasing CBAM certificates.

What’s still to be determined on CBAM?

Which sectors will be included, for a start. Organic chemicals, plastics, hydrogen and ammonia could be added to the existing list of cement, aluminium, fertilisers, power generation, iron and steel. ‘Indirect emissions’ are also under discussion – whether emissions from purchased electricity should be included as well as ‘direct emissions’ embedded in the production process. There are also timing issues. A proposal is still on the table for a two-year transition period from 2023 before full implementation in 2025, but it is likely that that timeline will be shifted.

How could CBAM affect trade?

The CBAM is WTO rules-compliant, so there’s a low risk of retaliation on trade. But producers all over the world will have to decide whether to pay up, decarbonise their production or take other measures such as changing trade partners.

What about unintended consequences?

There is some concern about the affordability of CBAM for trade partners from lower-income countries. CBAM is designed as a tool to aid global decarbonisation, but an unintended consequence could be that it serves to attract clean production to the EU and diverts dirty production elsewhere.

Could CBAM kick-start new carbon markets?

CBAM could prove to be a catalyst for other countries to move faster towards carbon prices comparable to Europe. Why let your producers pay taxes to the EU if the revenue could go into your treasury to help fund national decarbonisation goals? The UK and Canada both already have effective carbon markets and are also considering establishing CBAMs.

China has the biggest exposure to EU trade, and we expect the introduction of CBAM to spur an additional push to its own fledgling carbon market, which currently only taxes the power sector. The US, in contrast, is not materially exposed to EU trade. However, some individual states may see the CBAM as an opportunity to tighten their carbon market and pricing.