Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Assessing the risks to future oil demand

A weak world economy, the backlash against globalisation, and more ambitious climate policies threaten to put a brake on growth

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Is there an energy transition?

-

Opinion

Making low-carbon hydrogen a reality

-

Opinion

Rising electricity demand in Texas: the canary in the coalmine for the rest of the US?

-

Opinion

Deals show the enduring appeal of US gas

-

Opinion

2024 is a year of elections. What will they mean for clean energy?

-

Opinion

Home energy storage booms in the US

A hundred years after the end of the Great Influenza pandemic of 1918-20, scholars are still arguing over its effects. President Donald Trump was mocked recently for suggesting that the flu “probably ended the First World War,” but that is an assessment shared by some historians. So it is hardly surprising that there is still huge uncertainty over the ultimate consequences of the pandemic that is still raging.

That said, there are trends emerging that offer some pointers to the post-pandemic future, and in the past few weeks, Wood Mackenzie analysts have been working through assessments of what they might mean for energy. We recently published a report setting out three scenarios for how the world might evolve, looking at possible changes including a retreat from globalisation and a push by governments to implement climate policies such as the European Green Deal as part of their economic stimulus programmes.

One conclusion is that there is a good chance the path of oil demand may be permanently lower than we expected at the end of last year. That probably does not mean we have already reached “peak demand” for oil: a sustained decline in global oil consumption depends on large-scale electrification of road transport, and before the pandemic we were not on course to reach that point until the second half of the 2030s.

The world economy still runs on oil, and changing that will not be easy. The rebound in road traffic in China, even in Wuhan where Covid-19 was first identified, has been a reminder that much of the demand for fuel has been suppressed only temporarily, not forever. In the US, gasoline demand has been continuing to pick up from its lows in the first half of April.

However, weaker economies, restrictions on international travel and more aggressive climate policies all suggest long-term growth in oil demand could be slower than seemed likely before the pandemic.

Changes in behaviour have ambiguous implications for gasoline and diesel consumption. The case for working from home has been strengthened for some employers and employees. The social media company Twitter told staff this week that they would be allowed to work from home permanently, even after the pandemic is over.

On the other hand, people who are travelling generally seem happier to do so in private cars than on public transport. As restrictions are eased in Australia, for example, bus and rail use are recovering only very slowly. In China, rail ridership has picked up much more slowly than road traffic, with numbers on the Beijing Metro less than half their pre-virus levels.

The effect on jet fuel, though, is more clearly negative. Worldwide, there were about 36,000 commercial flights on Wednesday, just a little over one third of the number on a typical day three months ago. The upturn in flights so far has been tentative, and seems set to remain that way. Photographs of a packed US airliner posted on social media have sparked concerns about the risk of spreading infection, and some politicians have been suggesting that airlines should be compelled to give passengers more space.

As Paul Griffiths, chief executive of Dubai Airports, pointed out on CNBC, however, compelling airlines to operate flights at reduced capacity would be “ruinous” for their business. Some airlines have been talking about structural reductions in capacity. Delta Air Lines said this week it would stop flying Boeing 777s by the end of the year, meaning a reduction of about 25% in its wide-body fleet used mainly for international flights, and warned that by mid-2021 it expected to have about 3,000 more pilots than it would need.

Last year demand for jet fuel / kerosene averaged 7.86 million barrels a day. This year, it will be about 75% of that, Wood Mackenzie analysts forecast, and it is not expected to regain that 2019 level until 2022 at the earliest.

BP and Shell share their views on the energy transition

Bernard Looney, chief executive of BP, discussed the outlook for oil in a fascinating interview with the Financial Times this week, and he also suggested that demand for oil could be on a permanently lower path. “I don’t think we know how this is going to play out. I certainly don’t know,” he acknowledged. The pandemic has clearly altered the outlook, however. It had become more likely that oil demand would be lower, he said. “Could it be peak oil? Possibly. Possibly. I would not write that off.”

His conclusion: the pandemic “has only emphasised, re-emphasised, recommitted me to the need to take BP on the energy transition.” He accepted that he still had a job to do to prove the business case for that strategy, but promised that in September the company would provide investors with “the next level of detail” to justify its plans.

Valentina Kretzschmar, Wood Mackenzie’s vice-president of corporate research, said it was striking how Looney had inspired the company. “He galvanised BP employees,” she said. “Not just higher echelons in the company, but ordinary employees who normally don’t have a voice. They love working for BP; they are proud of their CEO.”

Meanwhile, Royal Dutch Shell held a webcast for investors this week, allowing a question and answer session that is unlikely to be possible at its annual general meeting in The Hague on May 19. Shareholders have been “strongly” recommended to “watch the meeting webcast in the safety of your homes and exercise your AGM voting rights online, ahead of the meeting”, rather than turning up in person.

As the transcript of the Q&A session shows, there was extensive discussion of Shell’s ambition to become a net zero emissions company by 2050. Like Looney, Shell’s chief executive Ben van Beurden said investors would have wait for details of how that ambition would affect the company’s investment strategy. What he would say is that Shell still plans to build a strong power business and develop other lower-carbon operations including chemicals and integrated gas. “We will continue to grow them disproportionately compared to, for instance, our core upstream theme,” he said.

He added that “on the other side of this crisis, we will be coming with a good update on how we see our strategy play out over the coming years.” The full transcript runs for 39 pages, and provides a very useful overview of what Shell’s leadership is thinking.

Saudi Arabia tightens its belt

The plunge in the price of crude has been a shock for all oil producers, from the smallest businesses to the largest countries, and Saudi Arabia showed that it too is feeling the strain. Saudi Aramco this week reported relatively healthy first quarter results, with a drop in free cash flow of only 14% to US$15bn. However, the Brent crude price averaged about $50 a barrel in the first quarter, and it has since fallen significantly.

To strengthen the kingdom’s finances, the Saudi government announced it was tripling its value-added tax rate, from 5% to 15%, effective from July 1, and suspending the cost of living allowance for state workers from June 1. It is also cancelling or delaying some operational and capital expenditures for government agencies, and cutting spending on major projects.

Mohammed al-Jadaan, the finance minister, said in a statement that the crisis caused by the global pandemic had created three shocks to the Saudi economy: the fall in oil demand, the shutdown of economic activity, and the need for increased healthcare spending. Each of those shocks “could in itself have an extremely negative effect on the performance and stability of public finance, had the government not intervened by taking measures to absorb them,” he said.

Saudi Arabia also announced it was doing more to help rebalance the oil market, cutting its production by a further 1 million b/d in June, beyond its share of the 9.7 million b/d reduction that the OPEC+ group agreed last month. The government said that in total, the cuts would take Saudi production next month to about 7.49 million b/d, 4.8 million b/d lower than in April. The United Arab Emirates and Kuwait also announced small additional cuts of 100,000 b/d and 80,000 b/d respectively.

The reductions in supply, along with the signs of an upturn in oil demand, have helped stabilise crude prices this week. Brent was trading on Friday morning at about $31.50 a barrel, with WTI at about $29.

In brief

There has been widespread speculation about the Trump administration doing more to help the US oil industry, but this week Dan Brouillette, energy secretary, poured cold water on those hopes. “For the time being, the first steps we’ve taken are going to be what we do,” he told Axios.

One issue that is still making waves in Washington is the question of how ESG criteria are used to determine which companies get financial support from the government programmes set up to offset the steep downturn in the economy. A group of Republican senators and members of Congress from Alaska, North Dakota and Wyoming has written a letter to President Trump, “urging the administration to take action against large American financial institutions that discriminate against American energy companies and their workers.” They argue that leading US banks and other financial institutions “continue unfairly to pick energy winners and losers in order to placate the environmental fringe”. In particular, they are concerned about BlackRock’s recent decision to stop investing in thermal coal.

Anyone interested in climate policy and “green stimulus” plans should keep an eye out for a new initiative from Johns Hopkins University. Its aim is to track the greenhouse gas emissions consequences of government policies during the crisis, allowing people to see which decisions will have the greatest long-term impact. Quantum Energy Partners, a Houston-based private equity firm, is in talks about raising $5.5 billion for a new fund to invest in opportunities in energy, according to Mergers and Acquisitions. The plan will be a test of investors’ interest in the oil and gas sector, which has fallen out of favour in recent years.

An “armada” of more than 30 tankers laden with Saudi crude is heading for the US to arrive in May and June, threatening to renew the pressure on oil storage capacity in North America.

Although the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany is largely built, there is a crucial final 100-mile section that needs to be completed, and the US is still apparently determined to stop it.

Poland’s coal-mining region Silesia has become a hot-spot for the Covid-19 coronavirus.

Joe Biden, who is set to be the Democratic presidential nominee, has agreed to set up “unity task forces” with his left-wing rival Bernie Sanders to advise him on policy. The climate task force includes Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the member of Congress who is one of the leading advocates of the Green New Deal programme. Her appointment suggests that Biden’s policy platform could be pushed towards greater radicalism in its strategies for cutting emissions.

Renewable energy is likely to generate more electricity than coal in the US this year, for the first time ever.

Almost 60% of seaborne thermal coal has higher production costs than the prices in the market last week, creating a grim backdrop for Australian miners aiming to refinance their debts.

Lower than usual demand for power in the UK means engineers have to work hard to keep the grid stable.

And finally: it has been another busy week for Elon Musk. He is a new father, and he has been battling local officials to reopen Tesla’s factory in the San Francisco Bay area, threatening to pull the company out of California because of his frustration with the opposition he has faced.

However, he has not been too busy to put his homes in the state up for sale. At least five have just gone on the market, on top of the two he had listed already. If you want to get an idea of how a tech billionaire lives, the homes are listed on Zillow.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Future energy: zero-carbon heating

Gavin Thompson — What is the future of energy in Asia after Covid-19?

North America’s crude oil storage problem

Anthony Knutson — Is green hydrogen metallurgical coal’s kryptonite?

David Victor— The pandemic won’t save the climate

Douglas McCauley and others — Eight ways to rebuild stronger ocean economy after Covid-19

Quote of the week

“The United States’ energy industry is strong, it will remain strong. It remains strong for a number of different reasons. We’re blessed with enormous resources here in America. But more importantly, we’re blessed with innovators in our industry. And they will continue to lead, as they have done for the past three, four, five decades, perhaps even longer.” — Dan Brouillette, the US energy secretary, was on TV this week making the case for optimism about the outlook for US oil and gas industry. In other interviews this week, he said stable oil prices would help US producers survive the downturn, to be ready to “explode” as economic activity recovers.

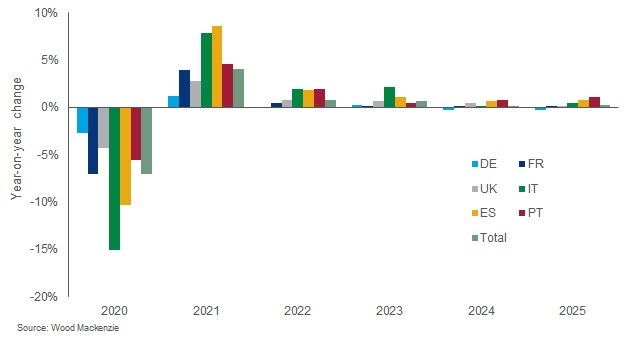

Chart of the week

This chart shows the forecast decline of power demand in the leading European markets caused by measures to fight the spread of the coronavirus. You can see that the countries that have adopted some of the most stringent restrictions on businesses and the public, Italy and Spain, have seen the sharpest falls in electricity consumption. Wood Mackenzie analysts expect total electricity demand in those markets to be down by 7% this year. We are forecasting a healthy rebound next year, but even so, it is likely to take a few years to get back to 2019 levels of demand.