Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Canada tries to balance energy and climate goals

The government has ambitious goals for cutting emissions. It doesn't want them to drive down oil and gas production

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

The first time Europeans came to Newfoundland, it did not go too well for them. Vikings founded a settlement in around 1000 CE at L’Anse Aux Meadows in present-day Canada, but lasted no more than 100 years, and all traces of their presence were lost for centuries. A millennium later, Norway’s Equinor has been exploring off the coast of Newfoundland with considerable success. It describes its assets off the east coast of Canada as “a high priority within our global portfolio.” The Canadian government last week approved Equinor’s plan to install a floating production facility at its Bay Du Nord discovery, in deep water about 500 km northeast of St Johns, the capital of Newfoundland and Labrador. The project is a pointer to how governments and companies may be thinking about the outlook for oil and gas developments after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the surge in prices that followed.

Canada’s decision to grant the environmental approval for Bay Du Nord was controversial, in part because Steven Guilbeault, the environment and climate change minister, is a former Greenpeace activist. The approval was published online late on Wednesday afternoon, with no fanfare announcing it. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government has set ambitious climate goals, including next zero emissions by 2050 and a 40-45% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030. Last month it published its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan setting out its proposals for achieving that interim goal.

The Canadian government’s strategy is to try to reconcile those objectives with continued production of hydrocarbons. It is planning a cap on emissions from oil and gas production, but says that does not mean it wants to force the industry to shrink. As the Emissions Reduction Plan puts it: “The intent of the cap is not to bring reductions in production that are not driven by declines in global demand”. The cap will also not take effect immediately. The government is still consulting with the industry, unions, environmental groups and the provinces, and has said the details will be published later this year or in 2023.

The objective is to keep Canadian hydrocarbons internationally competitive by reducing their emissions intensity. “Competing in this future means not only diversifying our energy mix, but also offering lower carbon oil and gas to the world,” the plan says. That means that every new oil and gas project will be required to be “best in class” in terms of emissions performance. The environmental approval for Bay Du Nord, for example, includes a stipulation that the project must have no routine flaring, and must cut the greenhouse gas emissions from its operations to zero by 2050.

The same day that Bay Du Nord got its approval, the government also granted a nine-month extension to the deadline for a decision on Suncor’s proposed Base Mine Expansion project. Guilbeault, the environment minister, wrote to Mark Little, Suncor’s chief executive, warning that “the project, as currently proposed, would likely cause unacceptable environmental effects within federal jurisdiction.”

The company has estimated that the expansion will produce 3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year over its lifetime. Guilbeault said he was pleased that “we have come to a shared recognition that emissions at this level may not align with the pace and scale of emissions reductions required to achieve our targets.” Suncor requested the nine-month extension to assess improvements to the project and other factors “to ensure alignment with our strategy to be a net-zero company”.

Equinor and its partners have not yet taken a final investment decision on developing Bay Du Nord, but the project will be helped if two further exploration wells in the area this year are successful. And it looks like exactly the type of project that would fit Canada’s strategy of offering lower-carbon oil and gas to the world.

Reconciling climate goals with the demand for reliable and affordable energy is never easy, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sending oil and gas prices surging, has thrown the challenges into sharp relief. But hydrocarbons with associated emissions that are as low as possible will have to be part of the solution. That is likely to including offshore production, which has an inherently low carbon intensity, as well as operations that use carbon capture and other technologies to curb emissions.

Oil sands profits soar

While Canada’s government has been looking ahead to oil industry’s future, in the present companies are generating a lot of cash. As Mark Oberstoetter, Wood Mackenzie’s head of upstream research for the Americas outside the Lower 48, puts it, oil sands producers have a lot of “torque” to the price of crude. When oil prices were low in 2020, the industry was in “dire survival mode”. As prices have rebounded, the industry’s profitability has soared.

If WTI crude were to average US$110 a barrel this year — somewhat higher than its current level of about US$96 a barrel — oil sands companies would be expected to make US$56 billion in cash flows after maintenance, operating costs, royalties and taxes. That is 2.4 times as much as they would make with WTI averaging US$70. The difference in the government share is even more marked. Royalties and taxes would be about US$41 billion in the high price scenario, three times as much as in the low-price world.

Those bumper cash flows are mostly not going to be recycled into increased capital spending, Oberstoetter says. The priority will be returning cash to shareholders with dividends and buybacks, and paying down debt. As of February, oil sands companies were planning lower capital spending this year than in 2019, adjusting for M&A activity.

Oil sands production is a long-cycle business: Suncor was aiming for its Base Mine Expansion project to begin construction in 2026, with production starting in 2030. A rapid response to higher oil prices was never going to be possible. But some increases in output from existing projects, including a ramp back at Suncor’s Fort Hills facility after cuts in 2020 and last year, as well as from some shorter-cycle producers, means that there is going to be some growth for the industry overall. As of February, midpoint production guidance from 28 Canada-focused companies was for 5.48 million barrels of oil equivalent in 2022, up 370,000 boe/d or 7% from 2021.

President Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw the approval for the Keystone XL pipeline project, which looms large in the political debate in the US, is something of a red herring in terms of determining Canadian production. The pipeline would not have been in service by now even if the president had allowed construction to continue, and there is no real evidence that Canadian producers are facing transport constraints.

Additional pipeline capacity was added when Enbridge’s Line 3 replacement came into service last year, and that seems to have helped cut the amount of oil moving by rail. In 2020, over 400,000 b/d was being loaded and exported by rail, but now that has fallen closer to 100,000 b/d. There is also more pipeline capacity set to be added in the expansion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline to British Columbia, which will allow greater exports, particularly to Asia and the west coast of the US.

Despite the lack of Keystone XL, Canada’s exports of heavy crude to the US have risen steadily in recent years, from about 2.55 million b/d in 2016 to 3.05 million b/d in 2021. If Canadian production keeps rising, additional export pipeline capacity will be needed. But that will be an issue for later in the decade, not right now.

In brief

The US benchmark natural gas price has risen to its highest level for more than 13 years. Front-month Henry Hub futures rose to a high of $6.54 per million British Thermal Units during the week, their highest level since 2008.

Gasoline prices, meanwhile, have been falling in the US, although they are still high by historic standards. The average price of a gallon is $4.116, according to the American Automobile Association, down from $4.318 a month ago.

The UK government has set out its new energy security strategy, setting a goal that 95% of Great Britain’s electricity should be low carbon by 2030. The plan includes a new ambition of up to 50 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030, including 5 GW from floating facilities in deeper water, a new licensing round for North Sea oil and gas, and accelerated investment in new nuclear power plants.

Large parts of Nigeria were again left without power for hours, three weeks after the previous widespread grid failure. (The recent Wood Mackenzie Horizons report by Benjamin Attia, Utility 3.0, discusses how distributed solar-and-storage grids can improve energy access and reliability in Afirca and around the world.)

President Pedro Castillo of Peru imposed a curfew in the capital Lima and the port of Callao following protests over rising fuel and fertiliser prices. The government earlier cut taxes on fuel, and is planning cuts in taxes on food, in response to public anger. Five people have died in the protests.

A US law aimed at banning imports of products made with forced labor in Xinjiang, China, comes into effect in June. The New York Times reported that “It remains to be seen how stringently the law is applied, and if it ends up affecting a handful of companies or far more.”

Other views

Flor Lucia De la Cruz and Bridget van Dorsten — Hydrogen: the US$600 billion investment opportunity

How is Russia’s war with Ukraine affecting gas markets and the global economy?

Simon Flowers — Exploration’s star is rising

Gavin Thompson — Asia’s LNG pain is Europe’s gain, for now

Neivan Boroujerdi — Domestic UK oil & gas can reduce reliance on energy imports

Jake Barnett and Patrick Peura — The future of investor engagement

Michael Grubb — The UK energy strategy is both cowardly and incoherent

Quote of the week

“Speaking for all of us at ExxonMobil, I want to emphasize that we stand with communities around the world in deploring Russia’s aggression and the devastation it has inflicted on the Ukrainian people. Within days of the invasion, we started work to exit the Sakhalin-1 project we have operated in Russia’s Far East since 2003, and announced that we would make no new investments in Russia. In consultation with the Biden Administration, we are taking the necessary steps to protect people and the environment, as we withdraw and transition operatorship.” — Darren Woods, chief executive of ExxonMobil, began his prepared remarks in evidence to a hearing of the House Energy and Commerce committee by explaining the company’s decisions over its operations in Russia. Along with senior executives from Chevron, BP, Devon Energy and other companies, he was questioned about the reasons why gasoline prices had risen, at a hearing titled: “Gouged at the gas station: Big Oil and America’s pain at the pump”.

Chart of the week

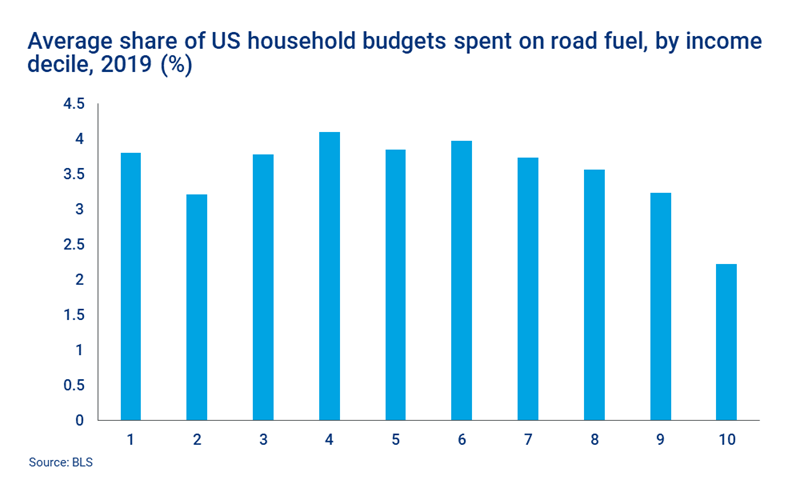

This is a chart I created using US government spending data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, showing the share of household budgets spent on gasoline. Each bar represents a decile (10%) of the income distribution, going from lowest to highest left to right. It is very clear that the burden of higher gasoline prices falls most heavily in the US on people on lower and middle incomes. In the lowest-income decile, an average of 3.8% of household spending went on road fuel and motor oil. For the highest-income households, it was just 2.2%. These are 2019 data, since when the average price of gasoline has risen by more than 50%, so currently you would expect all the spending on fuel to be correspondingly higher, except to the extent that the price effect is offset by decreased consumption. The shape of the chart is strikingly different from the UK, where people in the lowest income group generally do not own cars.