Five pieces of the circular packaging puzzle

Pricing, legislation, brand commitments, chemical recycling and bottlenecks will all influence long term circular packaging growth

1 minute read

David Buckby

Senior Analyst, Films & Flexible Packaging

David Buckby

Senior Analyst, Films & Flexible Packaging

David has almost a decade of experience in strategic market research and consultancy.

Latest articles by David

-

Opinion

Plastic demand could reduce by up to 30% in an accelerated energy transition scenario

-

Opinion

Polymer demand scenarios: a little more conversation, a little less plastic

-

Opinion

Will the EU’s flagship packaging legislation be transformative?

-

Opinion

Five pieces of the circular packaging puzzle

It’s no secret that the packaging industry is under ever-growing pressure to shift to a more sustainable future. The speed of this transition and the winners and losers within the industry are far from obvious, however. Pricing, legislation, brand commitments, chemical recycling and bottlenecks are five fundamental pieces of the sustainability puzzle.

In a recent insight, The circular packaging puzzle: five pieces shaping an uncertain picture, we consider how these factors will shape the future of the industry. Fill out the form for a complimentary copy, and read on for an introduction to some of the key themes.

Flexible packaging is a key piece of the circularity puzzle

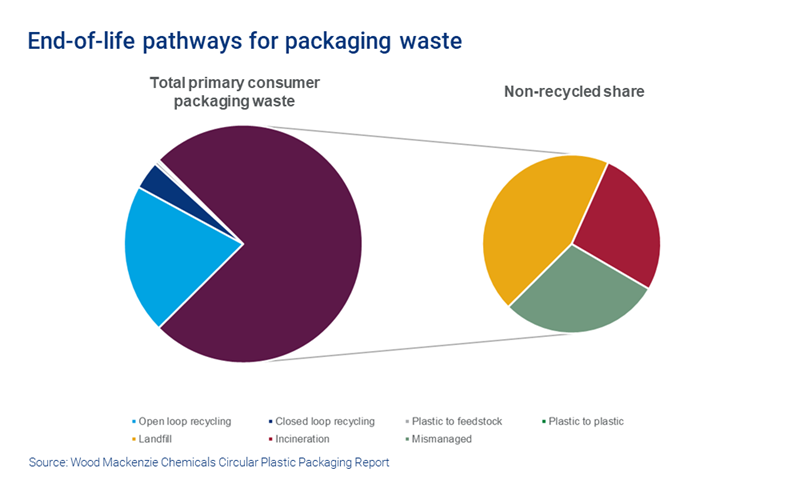

More than 75% of primary consumer packaging waste was not recycled in 2020. Of this, almost 30%, or more than 19 MT, was mismanaged. This includes leakage into the environment, open burning and unsanitary landfill. This is nearly six times the volume that went back into packaging through closed-loop recycling.

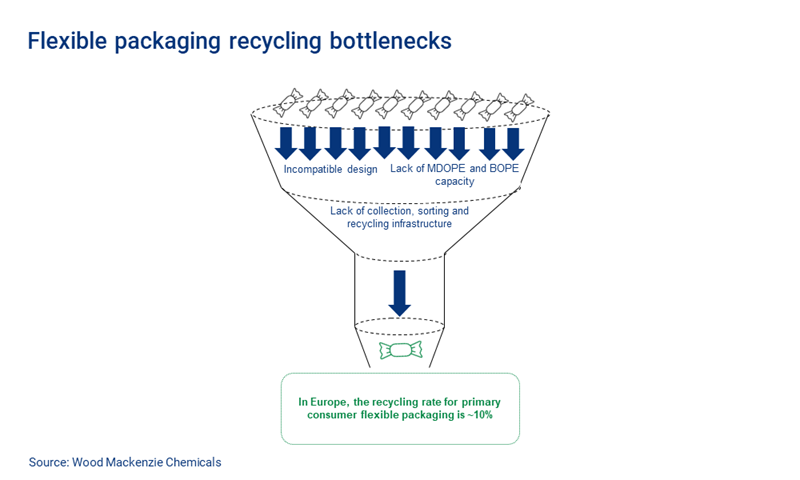

At the forefront of the problem is primary flexible consumer packaging. Accounting for around 40% of primary consumer packaging waste globally, its circularity is far worse than rigid packaging. In Europe, we estimate the recycling rates for flexibles and rigids at about 10% and 50%, respectively.

Household collection schemes for flexibles cover around two-thirds of the EU, but inadequate sorting ensures that the quality and price of most recycled material is typically poor. The market, therefore, provides little incentive for recyclers of flexible packaging and government interventions have been insufficient to change things.

Moreover, very little recycled content goes into flexible packaging. Due to food contact regulations, there is little to no mechanically recycled material in flexible food packaging. Many believe that the first step towards greater circularity in flexibles is ensuring that it is designed to be recycled. This has led to a proliferation of interest in mono-material flexible packaging.

Barriers and enablers of circular packaging growth

More sustainable packaging is more expensive. Uptake is impeded by ‘green premiums’, which typically arise because production costs of more sustainable materials are higher. Legislative reforms and brand commitments should eventually remedy this; it’s a question of when.

The good news for circularity is that over 60% of primary consumer flexible packaging (PCFP) globally is already mono-material. The less good news is that we do not expect this share to grow meaningfully until the 2030s.

As my colleague Andrew Brown wrote in Closing the loop on plastic packaging, creating a circular plastic economy will take more than a ramp-up in mechanical recycling. A successful chemical recycling industry, for instance, should mean more recycled content in packaging overall and we may see some shift from rigid demand to flexibles. While the technologies are still commercially nascent, 2020 and 2021 saw major new announcements of projects that will become operational pre-2025. This investment feeds into a CAGR of more than 15% for chemically recycled plastic packaging up to 2040.

The biggest bottleneck to circular packaging, though, is the lack of collection, sorting and recycling infrastructure. For flexible packaging, in particular, sorting is the biggest crunch point. Most waste sorting infrastructure is designed to sort rigid packaging: flexibles can wrap around rotating sorting equipment and disrupt operations. Flexibles are typically seen as a contaminant and end up in landfill or incinerated.

While existing sorting technology is improving incrementally, a step change may be possible by adding digital watermarks to packaging. The idea is that once packaging reaches waste sorting facilities, these marks can be scanned by cameras, enabling materials to be sorted into different streams based on their attributes. Industrial testing of this technology in Europe should conclude by Q3 2022.

Still, we expect circular packaging progress over the coming decades to vary markedly by region, polymer and application.

Mono-materials growth

Performance mono-materials that can be more easily recycled are significantly more expensive than incumbent multi-material structures. Legislation, design guidelines and brand commitments to 100% recyclable packaging should accelerate uptake, but progress so far has been marginal. The precise EU legal definition of a mono-material (to be determined) will also affect uptake.

Mono-material uptake also suffers from bottlenecks in production. Even if green premiums were lower, the capacity does not yet exist for barrier mono-material production to be rapidly ramped up. The requisite extrusion machinery is relatively scarce and will take years to install, especially with a limited number of machinery producers. Packaging redesign time is another impediment. For flexible food packaging, it typically takes around 18 months to develop and roll out a new design.

We currently expect mono-materials’ global share of flexible packaging to remain fairly steady in the 2020s. However, it is easy to envisage a tipping point towards mono-materials: the upside case is highly plausible.

To find out more, fill in the form at the top of the page for your complimentary copy of The circular packaging puzzle: five pieces shaping an uncertain picture. This includes charts on:

- Mono materials global growth to 2050

- Global chemical recycling growth

- Green premium ranges

- And more.