Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

The Biden administration seeks answers to high fuel prices

The president has asked refiners to increase output. Effective solutions will be more complex

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

“Successes are claimed by everyone; failures are blamed on one person.” The Roman historian Tacitus made that observation towards the end of the 1st century CE, and it remains a reliable rule today. You can tell that US energy policy over the past few years has been judged a failure, from the way that politicians, investors, lobby groups and businesses have been fighting to avoid being the one who takes the blame.

In the exchanges this week between the Biden administration and the US oil industry over the explanations for record US gasoline prices, there have been plenty of bad arguments and unsubstantiated claims flying around. But there have also been some constructive suggestions about ways that the financial strain and damage to the economy caused by high fuel prices could be alleviated.

The Biden administration hopes to put the US on course towards a future where road transport is largely electric, and gasoline and diesel prices have much less impact. But, as been shown in many different markets and sectors over the past year, it is a mistake to expect that that transition will be smooth. Large structural shifts in the energy system creates increased potential for supply and demand to get out of synch, and hence an elevated risk of the kind of price volatility we are seeing today. Energy policies will be more likely to sustain public support if they acknowledge that risk, and find ways to reduce the hardship caused by high prices.

President Joe Biden, his approval ratings sinking as gasoline prices have risen, made it clear that he wanted oil companies, and refiners in particular, to do more to cut the cost of fuel. His administration argues that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the primary cause of the added burden of fuel costs for American consumers, but says high margins for refiners are “worsening that pain”. Karine Jean-Pierre, the White House press secretary, said on Wednesday: “We are calling on them to do the right thing, to be patriots here. And not to use the war as an excuse, or as a reason, to not put out production, to not to do the capacity that is needed out there, so that prices can come down.”

In a letter this week to seven leading refining companies, the president focused on the loss of capacity during the pandemic, which has contributed to record margins around the world. He called on the companies to explain why the capacity had been lost, and said they now had “an opportunity to take immediate actions to increase the supply of gasoline, diesel, and other refined product you are producing and supplying to the United States market.” He added that he was “prepared to use all tools at my disposal, as appropriate, to address barriers to providing Americans affordable, secure energy supply”.

Jennifer Granholm, the energy secretary, will be holding an emergency meeting with industry leaders, probably next week, “to bring forward concrete, near-term solutions that address the crisis”.

As the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) and the American Petroleum Institute (API), the industry groups, pointed out in their response to the president’s letter, high prices for refined products are a global phenomenon, and focusing on US companies alone presents a misleading picture of the market. The charge that US refiners are choosing to raise prices by holding back output is hard to make stick. US refineries are already operating at about 94% of full capacity, well above their long-term average of 90%, according to the Energy Information Administration, and current margins provide ample incentive for them to maximise production. The industry groups observed: “Many facilities have safely delayed projects and/or maintenance so as to not take production offline and instead continue to provide supplies and build inventories.”

ExxonMobil also released a statement responding to the president, pointing out that it has been investing though the downturn, adding 250,000 barrels a day of processing capacity for US light crude. That is a significant increase, which by itself would replace about a quarter of the refining capacity the US lost during the pandemic. But refined product markets are global, and the big changes to world supplies will come as new refining projects in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Nigeria come on stream.

ExxonMobil’s suggestions to the administration for easing fuel prices in the short term include varying fuel specifications and waiving the provisions of the Jones Act, which restricts water transport between US ports to vessels that are built, owned, registered and crewed in the US. These moves could certainly have some effect at the margin. The Jones Act increases the cost of tanker transport around the US, meaning that it is typically lower-cost to serve east coast markets from overseas than from Texas and Louisiana, reducing the efficiency of the fuel supply system overall. But waivers for Jones Act restrictions will not make the difference between $5 and $3 for a gallon of gasoline.

Longer-term changes will be less appealing for politicians, especially for the administration contemplating the midterm elections in November, but could ultimately have a much greater impact. ExxonMobil argues that “clear and consistent policy that supports US resource development”, such as regular lease sales and streamlined regulatory approvals for infrastructure such as pipelines, would promote investment. As the plunge in crude prices of 2014-16 showed, strong growth in US oil production can be enough to bring about big changes in global markets, if given enough time to do so.

The API also published a list of “ten policies to unleash American energy and fuel recovery”, including authorising Congress to designate critical energy infrastructure projects, giving them streamlined permitting processes; dropping the Securities and Exchange Commission’s proposed climate disclosure rule; rescinding steel tariffs; and supporting training and education to nurture the skills needed to build and operate oil, gas and other energy infrastructure. Over time, it is very likely that those policies would support increased US oil and gas production and put downward pressure on prices.

One policy that the oil industry groups do not mention as a way to help ease the burden of high fuel costs is supporting adoption of electric vehicles and more demanding efficiency standards. Again, they are long-term responses rather than a short-term fix, but increased use of EVs and vehicles with higher fuel economy both help shield the consumers who buy them from some or all of the impact of expensive gasoline, and ease the upward pressure on prices by shaving off some demand.

However, there is a paradox highlighted by the AFPM and the API. As they wrote to President Biden, a key factor in several US refinery closures in recent years has been “lack of buyers willing to continue operating the facilities as petroleum refineries given growing rhetoric about the long-term viability of the industry.” If the administration wants companies to invest in increased US refining capacity, that is difficult to reconcile with a message that fossil fuels are on the way out. As the industry groups put it: “Refiners do not make multi-billion-dollar investments based on short-term returns. They look at long-term supply and demand fundamentals and make investments as appropriate.”

As governments worldwide seek to push energy systems towards lower-carbon technologies, this kind of tension, between projected future demand and the fuels that are needed today, will become increasingly common. If there is a positive side to the current crisis, it is that it has brought those issues sharply into focus. The energy transition poses challenges that many policymakers are only now starting to appreciate. If they want to make sustained progress with cutting emissions, they will have to find ways to do it that take those complexities into account.

Freeport LNG fire contributes to tighter European gas market

When Freeport LNG first talked about the impact of the fire at its plant in Quintana Island Texas, it said the facility would be offline for at least three weeks. This week, it updated that assessment, saying it now did not expect the plant to be fully operational again until late 2022. It is targeting a start-up for partial operations in about 90 days, “once the safety and security of doing so can be assured, and all regulatory clearances are obtained.”

The loss of LNG exports from Freeport is another blow for European gas consumers struggling with tight markets and high prices following the rebound in demand after the Covid-19 pandemic, and cuts in supplies from Russia tied to its invasion of Ukraine in February. As shown in this chart, the great majority of the gas exported from Freeport so far this year has been heading to Europe.

A new analysis by Massimo Di Odoardo, Wood Mackenzie’s vice-president of gas and LNG research, shows how the loss of supplies from Freeport will contribute to the tightening European gas market. If the plant comes back on line close to the timetable that Freeport has set, then about 4.5 million tons of LNG, equivalent to about 6.2 billion cubic metres of gas, will be lost from world markets. Meanwhile, there are upward pressures on demand. EDF of France has downgraded its expected nuclear production by about 2 terawatt hours per month, resulting in 6.5 bcm of addition gas demand through to the coming winter.

The most important factor for European gas markets, though, will be supplies from Russia. The current level of contracts could theoretically deliver 59 bcm of Russian gas through to March 2023. This week, however, Gazprom announced that flows through the Nord Stream pipelines from Russia to Germany would be cut sharply, blaming problems with turbines at a compression station. At the current level of flows through Nord Stream and other Russian pipelines, deliveries to Europe could be limited to 39 bcm. If Nord Stream is shut altogether, they could be just 17 bcm. Di Odoardo concludes: “The situation is evolving rapidly, and Europe may end up in a world without Russian gas sooner than expected.”

In brief

Baker Hughes has stopped providing services to Russian LNG projects, including Gazprom's Sakhalin-2 and Novatek’s Yamal LNG, the Kommersant newspaper reported.

A fire at the giant Urengoy gasfield in Siberia burned for about 90 minutes, creating some dramatic pictures. Gazprom said the incident caused no casualties, and would have no impact on its ability to meet its production targets.

President Biden plans to visit Saudi Arabia next month and expects to meet Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, setting a seal on his attempts to improve relations between the two countries. In his election campaign and earlier in his presidency, Biden took a more confrontational stance, saying he wanted to make Saudi Arabia “a pariah”.

The UK’s new windfall tax on oil and gas profits has already had “a dramatic effect” on the industry, forcing companies to reassess investment plans, independent producers have warned.

Other views

Simon Flowers — What price LNG?

Vanessa Witte — The US grid-scale energy storage market breaks the Q1 record

US Department of Energy Wind Energy Technologies Office — Wind turbines can stabilise the grid

Matthew Yglesias — The case against restricting domestic fossil fuel supply

Severin Borenstein — Myths that solar owners tell themselves

Quote of the week

“Due to a combination of several factors, the ability of our member countries — including our partners in the non-OPEC [group] — to continue to meet current demand in terms of supply adjustments is gradually being encumbered, because of capacity constraints. This has become now visible, in the sense that, with the exception of a handful of countries — Saudi Arabia, the UAE, to a very small degree Kuwait — most of the countries cannot increase. In fact, the deficit in terms of what we were supposed to cumulatively release to the market and what we have done so far, is about 2.6 million barrels a day… because there is no capacity.” — Mohammad Barkindo, secretary-general of OPEC, in a podcast with Jason Bordoff of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, warned that the OPEC+ group would face difficulties in meeting growing in demand for oil.

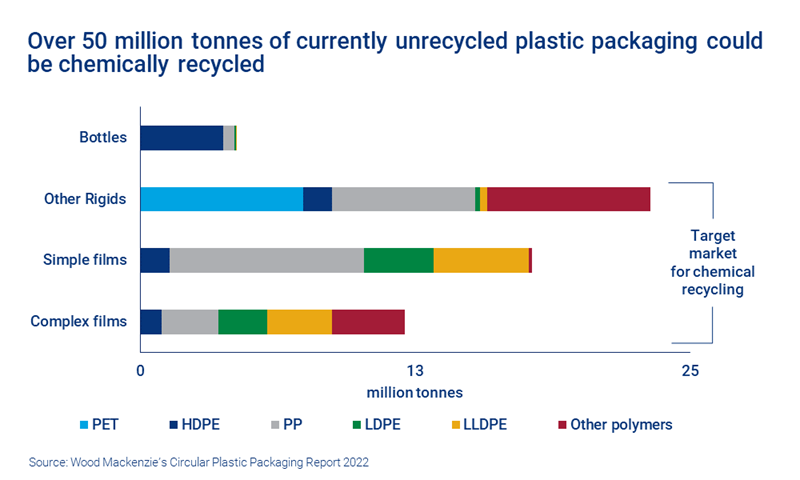

Chart of the week

This comes from a fascinating new report by Wood Mackenzie’s Olivia Loa and Alexandra Tennant, looking at the potential for chemical recycling of waste plastic. The current mechanical technologies used for recycling plastic play an important role in reducing the waste going to landfill or into the environment, and they are expected to continue to show healthy growth over the coming decades, but they have limitations, being suitable only for certain materials. Chemical processes can provide solutions for recycling plastic packaging that is unsuitable for current mechanical technologies. The chart shows more than 50 million tonnes per year of waste, including films and “other rigids” — rigid packaging other than bottles — that could be suitable for chemical recycling. By 2040, chemical processes are still expected to account for a minority of total plastics recycling worldwide, but their use is expected to grow much more rapidly than for mechanical recycling. The full report, presented as a deck of 21 slides, is full of detail and available as a free download. Well worth a read.