Ready to learn more about our oil & gas solutions?

US anger at OPEC+ production cut

The announced reduction in output has raised the temperature in Washington. Cooler heads are ultimately likely to prevail

10 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

What the "big beautiful bill" means for US energy

-

Opinion

Inside the ‘crazy grid’

-

Opinion

The Big Beautiful Bill is close to passing

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

“If you want a friend, get a dog.” The line, as used by Gordon Gekko in the movie Wall Street, described the life of a successful investor, but it can be readily applied to politics and international relations as well. Countries do not have friends, they have interests, and governments take decisions based on their perceptions of how those interests are best advanced.

Last week’s decision by the OPEC+ countries to cut their headline production limit by 2 million barrels per day provoked some anger in the US, but is entirely understandable when seen through that lens. It is also not as dramatic a move as much of the reaction suggested. The actual production cut is smaller than the headlines imply, and is coming as global demand for oil is faltering. The net impact on the market may be muted.

The reaction in Washington was certainly noisy enough. Democratic members of Congress proposed retaliatory measures, such as withdrawing US forces from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. President Joe Biden said the cut was disappointing, and described it as “unnecessary”. Karine Jean-Pierre, the White House press secretary, said it was “clear OPEC+ is aligning with Russia”.

President Biden visited Saudi Arabia only three months ago, and “reaffirmed the US commitment to help Saudi Arabia protect and defend its territory and people from all external attacks,” the White House said at the time. In the run-up to the OPEC+ meeting, his administration reportedly urged Saudi Arabia to oppose a deep production cut.

Nikki Haley, the Republican former governor of South Carolina and former US ambassador to the UN, suggested the rejection of those appeals had been predictable. “Don't be shocked when OPEC is not your friend and doesn't go and lift and raise production,” she told Fox News. “I mean, they did exactly what I think they wanted to do, which was stick it to Biden.”

Relations between the large oil-consuming countries and the OPEC+ group have been strained recently by the G7’s plan for a cap on the price of Russia’s oil exports. The proposed cap, championed by the US, is a novel policy experiment that seems unlikely to have much success in driving crude prices down. But just the fact that large consuming countries are attempting to cooperate is unwelcome for OPEC+ members. If the price cap does work at all, it could create a model to be used against other producing countries in the future.

Beyond any political tensions and geopolitical strategies, though, the OPEC+ countries had solid reasons to cut production. Brent crude had dropped by about $10 a barrel, from an average of $99.60 a barrel in August to an average of $89.90 in September, as fears grew about the possibility of a global recession. In China, economic growth has slowed sharply, in part because of lockdowns intended to prevent the spread of Covid-19. In the US, UK and the eurozone, central banks have been ramping up interest rates to control inflation. The downside risks to oil demand are significant.

The OPEC+ group’s announcement of a 2 million b/d production cut from November took many by surprise. But it is in reality less aggressive than that headline number suggests. Several members of the group are already producing well below their official maximums, so will not be affected by the new limits. Nigeria, for example, has a new “voluntary” maximum of 1.742 million b/d, but is currently only producing about 1 million b/d. Russia, too, is producing below its new limit of 10.478 million b/d.

There are just four countries carrying the burden of actually cutting production: Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Iraq. Together with some small adjustments from a few other countries, the actual reduction will end up being about 1 million b/d.

Meanwhile, global oil demand growth is slowing. World oil consumption is likely to be slightly lower in the fourth quarter of 2022 than in the same period of last year. The net result is that even after the production cuts take effect, global oil inventories will still be growing, at almost as fast a pace as seemed likely before the OPEC+ announcement, according to Wood Mackenzie’s latest Macro Oils report.

Prices did respond to the decision, with Brent rising from about $88 a barrel on the Monday before the OPEC+ meeting to about $98 by the end of the week, but they have subsequently dropped back a bit Ann-Louise Hittle, Wood Mackenzie’s head of Macro Oils, has left her price forecast unchanged: a strengthening during the rest of 2022, with Brent to average $97 per barrel in October, rising to an average of $103 per barrel for December

While the market impacts of the OPEC+ move are likely to be contained, the political consequences could be more lasting. Senator Charles Schumer, the Democratic leader in the Senate, said they were “looking at all the legislative tools to best deal with this appalling and deeply cynical action, including the NOPEC bill.”

Senator Bob Menendez, chair of the Senate foreign relations committee, said the Biden administration should immediately “freeze all aspects of our cooperation with Saudi Arabia, including any arms sales and security cooperation beyond what is absolutely necessary to defend US personnel and interests.”

However, there is a good chance that this rhetoric will also amount to very little in the end. Some version of the NOPEC legislation, which would bring the OPEC+ group under the remit of US antitrust law, has been brought to Congress many times over the past 22 years, but has never made it into the statute book.

President George W. Bush strongly opposed NOPEC legislation, and threatened to veto it, on the grounds that it would “result in a targeting of foreign direct investment in the United States as a source of damage awards and would likely spur retaliatory action against American interests in those countries and lead to a reduction in oil available to US refiners.”

It would also create an even wider breach in the relationship with Saudi Arabia, which has been a key focus for US foreign policy since the 1940s. The two countries share many aims in common, not least the preservation of a stable international trading system for oil. Although tempers may be frayed and feelings running hot in Washington DC at the moment, it is the cooler calculations of long-term US interests that are likely to prevail.

US refiners make the case against a new oil export ban

In so far as anything can ever be said to be settled in the world of energy policy, the debate over the now defunct US restrictions on crude oil exports appeared to be over. There is now widespread agreement that the near total ban, which lasted from 1975 to 2015, was a glaring strategic mistake. It punished US allies and customers around the world, distorted domestic markets and put a brake on production, all without doing much to achieve its supposed purpose of reducing fuel costs for American consumers.

However, it is always rash to assume that any bad idea has been killed off so thoroughly that it cannot possibly be revived, and that seems to be the case with the US oil export ban. Suggestions of possible new restrictions on exports of crude or petroleum products have been rumbling around, and the Biden administration has no options are “off the table” as potential responses to the OPEC+ decision.

A ban on refined products would at least avoid the specific ridiculousness of the crude ban that lasted until 2015. Because product exports remained unrestricted, prices in the US were set by global conditions, meaning that American consumers saw little or no benefit from lower domestic crude prices. But restrictions on product exports would also cause significant market distortions.

The heads of the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers and the American Petroleum Institute, the industry groups, last week wrote to Jennifer Granholm, the energy secretary, urging her not to impose a ban on fuel exports. Restricting those exports “would cut off important supply from the international market, putting upward pressure on prices, threatening the global flow of essential energy, undermining US allies and creating negative global economic consequences, including here in the United States,” they wrote.

Record high US gasoline prices earlier this year, a fast-approaching midterm election, and an administration that is casting around for solutions to its energy challenges, are the kind of conditions that can foster attention-getting but ill-advised policy choices. But the weight of opinion against oil export bans is so solid, it would be a big surprise if the administration now decided to introduce one.

In brief

The Biden administration is looking at easing the sanctions on Venezuela, potentially allowing Chevron to produce more oil, the Wall Street Journal reported. Wood Mackenzie’s Marcelo de Assis assessed Venezuela’s “road to recovery” back in April, and concluded: “Contractual issues, labor shortages, equipment availability, PDVSA financial strength and other factors will prevent production being able to ramp up at a breakneck speed.”

Britain could face rolling power cuts lasting up to three hours in a worst-case scenario this winter, the network operator National Grid has warned. Newspapers reported that the government had been working on a campaign to encourage consumers to use less energy, but it had been canceled by Liz Truss, the prime minister.

The UK government has also sparked outrage among renewable energy advocates with a plan to ban solar arrays from most farmland in England.

The electricity grid in Greece has run for a while entirely using renewable power, for the first time in its history. The 100% renewable period was only temporary, of course: it lasted about five hours.

Other views

Simon Flowers — The energy crisis: what’s on CEOs’ minds?

Murray Douglas — What will REPowerEU and the Inflation Reduction Act mean for hydrogen?

Gavin Thompson — Making CCUS work in Asia Pacific

Cat Rutter Pooley — How to make a mess of an energy windfall tax

Fred Pearce — Why the rush to mine lithium could dry up the high Andes

The Economist — The energy transition will be expensive. But not catastrophically so

Dan Reicher — Those old power plants? Now we have the means to turn them green

Paul Wolfram et al — Using ammonia as a shipping fuel could disturb the nitrogen cycle

Quote of the week

“These things take time. So if you come and tell me: ‘your gas is going to be valuable for me from 2026 to 2036, and beyond that I don’t want your gas any more’, who is going to invest? The investments we are going to be putting in, overall with NFS [North Field South], with NFE [North Field East], with the shipping and everything, is probably like $100 billion. So who is going to invest that kind of money unless they have visibility of what’s going to happen in the future? Governments have to signal that clearly to companies, and ensure they understand that: we need the transition, but we need to do it sensibly and practically. It’s not just a nice political discussion to talk about ‘green’; it has to be a reality that can be put on the ground and actually be achieved by these oil and gas companies. Otherwise we’re going to have these shocks again and again.” — Saad Sherida Al-Kaabi, chief executive of QatarEnergy, had some clear messages for European policymakers when he spoke at Wood Mackenzie’s Energy and Natural Resources Summit for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. The summit was held in London on September 27.

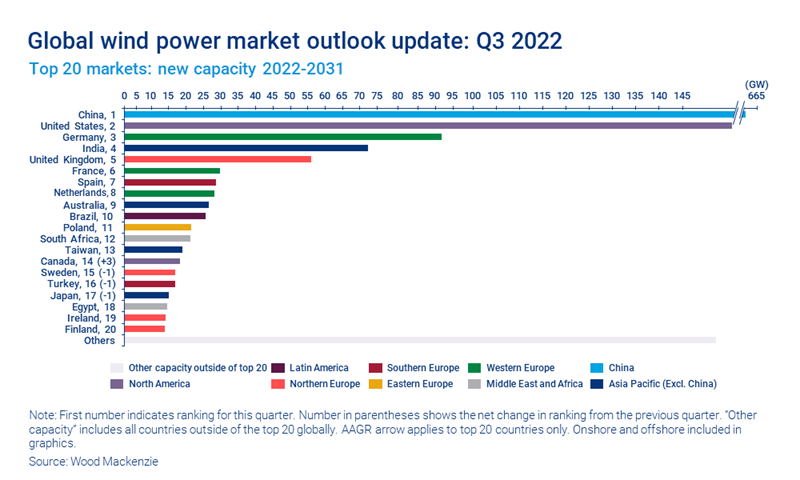

Chart of the week

This comes from our latest Global Wind Power Outlook for the third quarter, produced by Wood Mackenzie’s Global Wind Markets Service. The big news in the forecast is the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law by President Biden in August. The legislation extends the US production tax credit for wind power, a move that we forecast will increase installations between now and 2030 by 43%, compared to what would have happened without the extension. On a global scale, though, the big story is China. Over the ten years 2022-2031, roughly half of all the wind generation capacity added worldwide will be installed in China. The projections are a vivid reminder of just how important China is for the global transition to low carbon energy.