Interested in learning more about our oil & gas solutions?

Banks assess the impact of climate commitments

Lenders can still finance new oil and gas development, but emissions goals mean the balance of their operations is shifting

10 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

-

Opinion

What the conflict between Israel and Iran means for energy

It was one of the more dramatic moments in a US congressional hearing in recent years. When the chief executives of the big US banks were giving evidence to the House financial services committee earlier this month, the progressive Democrat Rashida Tlaib asked them whether they had a policy of not providing financing for new oil and gas production. Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, replied: “Absolutely not. And that would be the road to Hell for America.” Tlaib responded that JPMorgan Chase customers should probably close their accounts.

There has been an increasingly public debate this year over US and European banks’ climate pledges and lending policies. Environmental groups such as the Sierra Club argue that there is an irreconcilable contradiction between banks’ claims to support the goals of the Paris climate agreement, and their continued lending for new oil and gas development. US Republican politicians have argued that the banks’ emissions goals have meant they have failed to support fossil fuels sufficiently, driving up prices and undermining energy security.

The debate has been helpful in terms of clarifying what financial institutions can do to support the transition to low-carbon energy, and what actions could be counterproductive. Banks can, in fact, still finance new oil and gas production while meeting their goals for emissions reductions. But the new frameworks of commitments and pressure from policymakers and regulators are creating tensions that still need to be worked through.

The banks’ approach to addressing the threat of climate change took a big leap forward last year, with the launch of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, which includes the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, with 117 member including all the leading US and European banks. The NZBA banks, which account for about 40% of total global banking assets, are committed to “aligning their lending and investment portfolios with net-zero emissions by 2050”.

Environmental campaigners have argued that that commitment means the banks should immediately stop all financing for new fossil fuel production. At a time when the world is crying out for increased supplies of energy, and particularly natural gas to replace flows from Russia, that argument has raised alarms about whether the industry is being starved of the financing it needs to meet future demand.

The tensions broke out into the open earlier this month with reports that leading US banks, including JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America, had threatened to quit GFANZ. A particular pain point has been the potential interaction of membership with the new US rules on climate disclosures proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Those rules would, among other provisions, require companies to set out their plans to meet any targets. Bankers have warned that the rules could create new risks of legal action over climate commitments.

The banks’ concerns were heightened by an update in June to the UN’s Race to Zero campaign, which prescribes mandatory climate criteria for the Net-Zero Banking Alliance. The new guidance for Race to Zero for members to “phase down and out all unabated fossil fuels”, and a requirement for members to “restrict the development, financing and facilitation of new fossil fuel assets”. It also explicitly referred to the International Energy Agency’s 2021 Net Zero scenario, which envisions no new oil and gas fields being needed.

Apparently in response to those concerns from banks, the UN issued revised guidance earlier this month. It now requires members to commit to phasing unabated fossil fuels “down and out”, in line with “appropriate, global science-based scenarios” for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. But it does not require a particular timetable or insist that banks follow the IEA’s Net Zero scenario specifically.

Kavita Jadhav, a research director in Wood Mackenzie’s corporate research team, says the revised language brings the Race to Zero into line with the original guidance from GFANZ, which very clearly did not insist on stopping all financing of new oil and gas development. Instead, it was designed to encourage lenders and investors to steward and engage with companies to support a transition to Paris-aligned business models. “It does seem like there has been a rethink there,” she says.

“For GFANZ, this is definitely a good thing. Membership had been starting to mean ‘all or nothing’ in terms of financing fossil fuels, and that was just not realistic. Now it is going back to something that is more practicable. An approach that reflects real-world constraints is critical both for GFANZ to retain its current members, and to bring in the remaining large financial institutions that have not yet joined.”

The revised guidance does not mean that membership of GFANZ will have no effect on banks’ operations. The requirement to align with a scenario for 1.5 °C of warming will constrain them, even if they have more flexibility in how they comply. The big US and European banks have also set intermediate targets for 2030, which will shape their decision-making.

JPMorgan, for example, has a 2030 target for its clients in the oil and gas industry of a 35% reduction in operational carbon intensity, and a 15% reduction in end-use carbon intensity, by 2030. Bank of America’s 2030 targets for energy are a 42% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 (operational) emissions intensity, and a 29% reduction in Scope 3 (supply chain and end-use) emissions intensity.

These targets mean that although the banks can continue financing new oil and gas development, they may be more selective about what they support. They will work with clients to help achieve emissions reductions. They will have incentives to support emissions-reducing activities, including carbon capture, use and storage and carbon offsets. And because the targets are framed in intensity terms, they will have incentives to support financing of low-carbon energy such as wind and solar power that will reduce the overall emissions of their portfolio per megawatt hour or equivalent.

The impact of banks’ climate policies on investment in oil and gas is difficult to quantify. Anecdotally, curbs on financing have had some effect, but over the past few years the volatility of commodity prices has been a more important factor.

As Erik Mielke, Wood Mackenzie’s head of corporate research, puts it: “The reduction in investment in upstream in recent years is not because of a lack of finance. It’s because of a chronic lack of stable returns, which has finally led to improved corporate capital discipline.”

The new guidance from the UN should allow enough leeway for banks to support badly-needed investment in new oil and gas supply, while they work to curb emissions. But it will take time to see how the new framework shakes down.

One change that could have a rapid positive impact is finding ways to streamline the requirements for data collection and record-keeping created by climate goals. Already two pension funds lave left their GFANZ alliance because of resourcing problems, the Financial Times reported. Reducing that administrative burden could help encourage members to stay in, at the risk of raising doubts about whether their climate strategies are having the desired effects.

We can expect plenty more scratchy exchanges between financial institutions and policymakers in the years to come.

Nord Stream explosions fuel speculation

Large leaks on the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea were discovered on Tuesday, following large underwater explosions recorded by seismic networks. The obvious conclusion was that the pipeline had been sabotaged, and the EU issued a statement saying “all available information indicates those leaks are the result of a deliberate act”. It added: “Any deliberate disruption of European energy infrastructure is utterly unacceptable and will be met with a robust and united response.”

However, the EU stopped short of ascribing blame to a specific country. Speculation centred on Russia, and western intelligence officials reportedly said Russian navy vessels had been spotted in the area close to the leaks.

The short-term impact on European gas supplies is zero. Nord Stream 2, although completed, has never come into operation, and the flows on Nord Stream 1 had been shut off by Russia indefinitely in response to European countries’ support for Ukraine.

For the longer term, the attack sends a strong signal about Russia’s future energy relationship with Europe. Eventually, depending on how the political situation evolves, it might be possible for Russia to restore its gas exports to other European countries. The damage to the Nord Stream system means that it will not be able to play a role in rebuilding that relationship until after the complicated task of repairing it is complete, and possibly not ever.

Wood Mackenzie’s gas research team said the impact of the attack on European gas prices had been to “put upward pressure down the curve as it becomes less likely that Russian flows could possibly return in the future.”

The damage to the pipeline has raised fears that other pieces of energy infrastructure could come under attack. Jennifer Granholm, the US energy secretary, said: “Everybody should be on high alert.”

In brief

Hurricane Ian cut a devastating path across Florida, making landfall as one of the five strongest storms ever to hit the state. Ron DeSantis, Florida’s governor, said the hurricane had caused a “500-year flooding event”. An early estimate of the death toll was “in the hundreds”, while the cost of recovery was put at up to $100 billion. At the time of writing, the hurricane was headed towards South and North Carolina.

EU energy ministers agreed a package of measures to respond to the energy crisis. They include a 5% mandatory reduction in peak electricity demand, a 10% voluntary reduction in total electricity use, and a cap of €180 per megawatt hour on revenues for “inframarginal generators” including wind, solar, nuclear and lignite plants. They also agreed a new “solidarity levy” on oil, gas, coal and refining company profits above 120% of their average yearly taxable profits since 2018.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Oil in a decarbonising world

Gavin Thompson — In conversation with Asia Pacific’s energy and natural resources leaders

Sagar Chopra — Floating solar: still niche or ready for the mainstream?

New US solar contract capacity sees record growth in Q2

Jordan McGillis — The real divide on permitting reform is not Democrats vs Republicans

Philippa Nuttall — Heating homes with hydrogen is bad for both your wallet and the planet

Alec Stapp — What many progressives misunderstand about fighting climate change

Ted Nordhaus — Twilight of environmental idols

Quote of the week

“I will make sure there is local consent if we are to go ahead, in any particular area, with fracking... We need to explore where there is local consent and where there isn’t. And we are still doing that work. I don’t think we should rule out the whole of Lancashire.” — Liz Truss, the new prime minister of the UK, faced questions on BBC Radio Lancashire about her hopes of kick-starting the country’s unconventional oil and gas production, after lifting a ban on hydraulic fracturing imposed in 2019. Some local Conservative MPs have opposed the resumption of operations in Lancashire, which is seen as one of Britain’s most promising regions for shale development. Public and political opposition, despite the government’s support, remains a challenging issue for would-be shale developers in the UK.

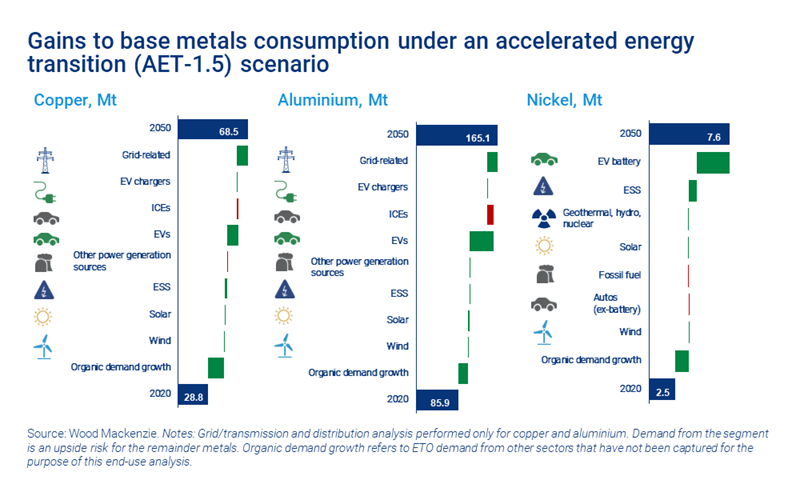

Chart of the week

This is a chart that was presented by Bhavya Laul, Wood Mackenzie’s senior analyst for base metals markets, at our recent Metals & Mining Forum. It underlines a point that we have been making for a long time: the path to a low-carbon economy has to be built with metals. The chart shows three examples: copper, aluminium and nickel, with at the bottom actual demand in 2020, and at the top our projected demand in a scenario for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, the aspirational goal of the Paris Agreement. The prospective increases are a rough doubling in demand for copper and aluminium, and a tripling in demand for nickel. If you look at the breakdown of the projected increases, you can see that two markets in particular drive the expected growth in demand: electric vehicles and the power grid.