Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Why the US oil industry could call for a carbon tax

Carbon pricing can offer a simpler and more transparent way to set incentives to cut emissions

9 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

James Callaghan, UK prime minister 1976-79, liked to say that opponents who wanted an election were “like turkeys voting for Christmas”. The American Petroleum Institute’s possible support for a carbon tax, reported by the Wall Street Journal, might look like a similarly self-destructive choice. But in fact there are good reasons why the members of the API, which include almost all the leading oil and gas companies operating in the US, might want such a tax.

The group is still debating the proposal. The API last year adopted its Climate Action Framework, which includes support for a national carbon price, but members are divided over whether a tax is the best way to implement it. Megan Bloomgren, a senior vice-president at the API, said: “We are focused on analysing solutions for the most transparent and impactful way to reduce emissions at the lowest cost to American families, and this proposal is part of that process.”

US adoption of a carbon tax still seems unlikely, for the next few years at least, even if the API does come out in support. Garrett Graves, a Republican member of the House of Representatives Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, is quoted in the WSJ article describing the idea of a carbon tax as “just idiotic right now”, given that US retail gasoline prices are close to record highs. A modest carbon tax of $20 per ton of carbon dioxide was discussed by some Democrats last year, but failed to win sufficient support in Congress.

But the US is unusual among large developed economies in not setting a national price on carbon emissions, and support is growing for a change in that position.

The different views inside the API in part reflect differing degrees of ambitions in the climate goals set by member companies. Shell, for example, is aiming for net zero emissions, including from the energy products it sells, by 2050. It said it was committed to “convening important conversations, including at API, that could ultimately lead to putting a price on carbon.” Many US oil and gas companies have emissions goals, but they generally cover only Scope 1 and 2 emissions, from their own operations and their purchased energy, not Scope 3, from the products they sell.

Despite these differences, however, all oil and gas companies are under similar pressures from their stakeholders — investors, governments, sometimes staff and customers — to curb their emissions. Putting a price on carbon would create an additional financial incentive to support those efforts. Supporting the policy is a way for the industry to signal that, in the words of the API: “We share with global leaders the goal of reduced emissions across the broader economy and, specifically, those from energy production, transportation and use by society.”

Another advantage of a carbon price is that it can be a simpler and more transparent mechanism than the current array of complex and interlocking regulations relating to emissions. As part of a political deal to enact a carbon tax or other price mechanism in the US, other emissions regulations could be scrapped. The API is not arguing for a complete clear-out of emissions regulations, but it does argue that “if a price on carbon is introduced, it should minimise the burden of duplicative regulations.”

A carbon price would give businesses more freedom to decide for themselves how to cut emissions to reduce their liability. Current regulations and subsidies have widely varying costs in terms of avoided emissions. US subsidies for electric vehicles cost US$795 per ton of carbon dioxide emissions cut, according to research published last year. That is more than 20 times Canada’s carbon price, which has just increased to C$50 (about US$39) per ton. But the cost of the EV subsidy is not obvious and hard to calculate, whereas the carbon price is easy to grasp.

Under the API’s principles for carbon pricing, the transparency would extend to consumers. It argues that “a government policy-imposed carbon price should be disclosed at the point of retail sale.” That would at least help drivers find someone else to blame when gasoline prices rise.

One other argument for a carbon price is that it can provide greater confidence for long-term planning, especially for investments in emissions reduction technologies. Canada’s carbon price is intended to rise to C$170 per ton of carbon dioxide in 2030. It is of course possible to be sceptical about whether it will in fact rise that high, but the plan provides a reference point for everyone making decisions that will have implications for emissions.

Yet despite all the arguments for carbon pricing, which have proved compelling in most other developed economies, and the signs of growing support in the US, there is still an uphill battle to be fought before it can be made a reality in the US. At the moment, there is much more activity in cutting taxes on energy than in putting them up.

The pressure that might change this attitude comes from outside not inside the US, says Joshua Firestone, a principal economist in Wood Mackenzie’s fiscal service. The EU is continuing to make progress towards introducing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), often known as a “carbon tariff”, charged on imports based on their associated emissions. The idea is to level the playing field for European companies that have to pay the cost of carbon under the EU’s emissions trading system, and to prevent “carbon leakage” from businesses relocating to jurisdictions where emissions are not priced.

If US exporters in covered sectors are not paying a cost of carbon, they will have to pay for CBAM certificates, and EU member states will collect the revenue. That looks like an unpalatable prospect for the US, which could be avoided by putting a price on carbon.

As a possible first step, there might be a way for the US to impose a carbon price only on products being exported to the EU and other jurisdictions with a CBAM. It could be quite an appealing political slogan, Firestone suggests: “We’re going to clean up our emissions. And we’re going to make Europe pay for it.”

In brief

Gazprom cut off supplies of gas to Poland and Bulgaria, saying that they had refused to pay in roubles as the Russian government has demanded. The move led to volatile trading that drove front-month TTF futures briefly to a high of $36 per million British Thermal Units. Wood Mackenzie analysts said the lost flows of Russian gas into Poland were likely to be replaced by increased LNG imports from the US.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, said agreeing to pay for gas in roubles would be “a breach of the sanctions” imposed by the EU. However, customers in countries including Germany and Hungary have been looking at ways to comply with Russian demands to keep the gas flowing. Uniper of Germany has said it will pay for Russian gas in euros that are converted to roubles. A spokesman told the BBC: "We consider a payment conversion compliant with sanctions law and the Russian decree to be possible.”

Meanwhile, Algeria threatened to cut off gas exports to Spain if any of the gas it sells there is redirected to other markets. The move was a response to Spain’s recent alignment with Morocco, which is engaged in a simmering dispute with Algeria over the Western Sahara region. Spain attempted to reassure Algeria, promising “that it will not send its imported supplies of natural gas to Morocco” or "a third destination".

The US Department of Energy has made a conditional commitment to provide a US$504.4 million loan guarantee to the Advanced Clean Energy Storage Project in Utah, a first-of-its-kind low-carbon hydrogen production and storage facility that will be used for long-term seasonal energy storage. The facility will produce hydrogen with alkaline electrolysers and store it in two salt caverns, for use in an 840 megawatt hydrogen-capable CCGT plant. The plant will initially run on a blend of 30% green hydrogen and 70% natural gas from 2025, rising to 100% hydrogen by 2045.

Renewable energy could be “the greatest peace plan this world will ever know,” US energy secretary Jennifer Granholm has said. She was speaking at a forum on offshore wind with Kadri Simson, the EU’s energy commissioner. Granholm also this week gave evidence to the House Committee on Energy & Commerce, where the promised that her department was “using every tool available to increase oil supply”.

Earlier this month, the Department of the Interior launched the Biden administration’s first onshore oil and gas lease sale, following an injunction from the court in the Western District of Louisiana. The acreage being put up for sale is only about 20% of the land originally nominated for possible leasing.

Shareholders in Citigroup, Bank of America and Wells Fargo have by large majorities rejected proposals calling for the banks to stop lending that would finance new fossil fuel supplies.

A severe heatwave in India, arriving earlier than usual this year, has caused disruption across the country.

Other views

Simon Flowers — How the Russia/Ukraine war changes energy markets

How Russia’s war with Ukraine is changing the metals and mining trade

Luke Lewandowski — China remains the global wind powerhouse

Bruna Angel, Emma Liu and Salmon Lee — Tackling the textile industry’s carbon footprint

This eminent scientist says climate activists need to get real

Quote of the week

“The ESG movement is nothing but a slippery slope whereby our states and our people will be forced to bend the knee to the woke capitalists or suffer financial harm.” — Riley Moore, state treasurer for West Virginia, criticised new ESG ratings for state and local governments launched by S&P Global Ratings. His comments reflect broader opposition in the Republican party to current trends in ESG investing; a view that is expected to become increasingly significant in Washington if Republicans retake control of Congress in this year’s midterm elections.

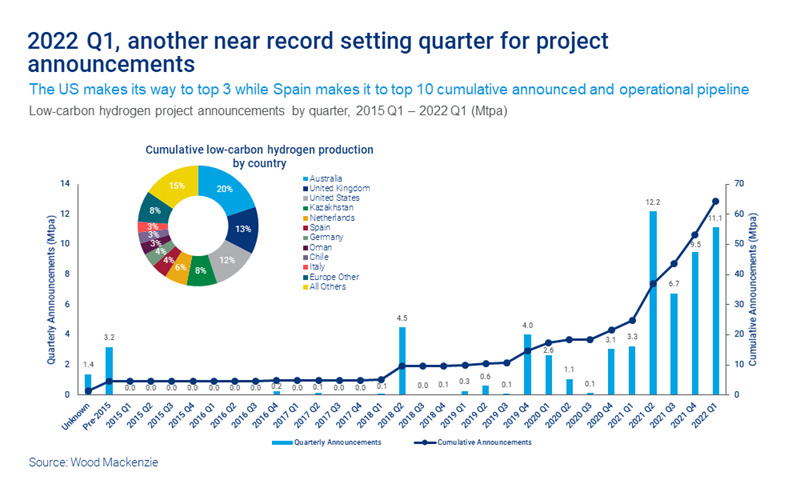

Chart of the week

This week we held our first Low-Carbon Hydrogen Conference in London, with speakers from Wood Mackenzie and across the industry. This chart, from our recent Q1 Hydrogen Market Tracker, is a good illustration of why there is so much interest in data and analysis on the sector. In the short term, costs for both blue and green hydrogen have been rising, because of higher energy prices. But that has not done much to hold back the industry’s growth. Announcements of new hydrogen projects came at a near-record pace in the first quarter, with another 11.1 million tons per year of low-carbon production capacity planned. The flow of announcements underpins our forecast that by 2050, the hydrogen market will triple in size to 281 Mtpa, dominated by green hydrogen.