Making Australia an energy transition leader

Investment barriers still to be tackled

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Unlocking the potential of white hydrogen

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

The Edge

Are voters turning their backs on the EU’s 2030 climate objectives?

-

The Edge

Artificial intelligence and the future of energy

-

The Edge

A window opens for OPEC+ oil

-

The Edge

Why higher tariffs on Chinese EVs are a double-edged sword

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin oversees our Europe, Middle East and Africa research.

Latest articles by Gavin

-

The Edge

Unlocking the potential of white hydrogen

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

The Edge

Are voters turning their backs on the EU’s 2030 climate objectives?

-

The Edge

What will define LNG’s three phases of market growth?

-

The Edge

The coming low carbon energy system disruptors

-

The Edge

Could US data centres and AI shake up the global LNG market?

Australia has been a leading exporter of energy and metals for decades. A stable investment environment for the exploitation of its giant gas, coal and iron ore resources has positioned the country as a trusted supplier to Asia’s booming economies.

And just as Asia’s economic transformation would not have been possible without Australian energy and metals, the region’s future decarbonisation will require major investment in Australian low-carbon LNG, renewables, green hydrogen and carbon capture potential.

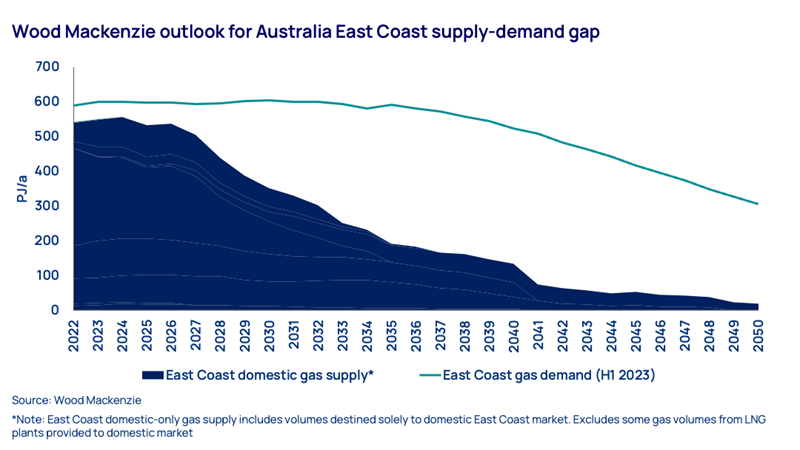

Yet today Australia’s progress towards fulfilling its central role in Asia’s transition is at risk. A lack of policy support has stifled investment in new gas supply, contributing to an energy crisis and creating rifts with LNG producers and buyers. Rising intermittency and grid congestion are stalling investment in the renewables that are central to major domestic emitters’ plans to decarbonise. And despite its ‘green energy hub’ ambitions, Australia has yet to fully kick-start its carbon capture and storage (CCS) and green hydrogen industries.

How did Australia reach this impasse? What steps does the government need to take? And can Australia attract the necessary levels of investment? Gavin Thompson, Vice Chair for Asia Pacific research, takes a deeper look.

Policy uncertainty has stalled much-needed gas investment

The past year has been bruising for Australia’s gas industry. Underperforming coal-fired generation and insufficient renewables triggered a long-predicted gas supply crunch in the main domestic gas market on the east coast. Cue government intervention, including price caps.

Changes to Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism to expedite reductions in greenhouse gas emissions have also caused consternation. The need for Australian LNG projects to reduce their carbon footprint has long been clear, yet the Safeguard Mechanism is far from a complete decarbonisation roadmap, with minimal incentives or funding for CCS.

But what really worries the industry is under-investment in gas resources. This could result in supply contracted for LNG exports being diverted into the domestic market. Some Asian governments and buyers have taken the unusual step of publicly expressing their unease at the prospect.

Developing new gas supply would meet domestic needs and ensure LNG contracts are fulfilled, maintaining Australia’s reputation as a secure investment environment in the process. Ironically, a failure to do so would also likely lead to higher emissions at home and in Asia as coal would fill the gap.

More gas will benefit growth in renewables

Australia has made huge progress in renewables, more than tripling the share of wind and solar in its power mix to over 30% since 2010. But as capacity has increased, the familiar issues of grid congestion, connection queues, revenue uncertainty and public opposition are now widespread and growing. A lack of flexible power capacity to balance increased intermittency is another factor that has resulted in no new large-scale renewable projects moving ahead so far this year.

Battery storage can help. But today’s capacity – only around 1 GW of operational capacity, with a further 3 GW expected by 2025 – won’t be enough to support the 40 GW of renewables already operational in Australia. Developing more gas would support the growth in wind and solar and avoid Australia heading towards an increasingly unreliable power system.

Why Australia must act now

Australian policymakers seem caught between a rock and a hard place. Intervention in the gas market has led to cries of meddling, while renewables, grids, hydrogen and CCS are desperate for increased policy support.

Additional gas supply is an obvious step to address the immediate east coast crisis and assuage the fears of Asian LNG importers. And while this has been something Canberra has been reluctant to do, Resources Minister Madeline King recently emphasised government support for gas as a key part of Australia’s net zero ambitions at this year’s APPEA conference in Brisbane. Hopes have been raised that Australia’s gas sector has passed ‘peak intervention’, but more clarity is needed around regulatory and environmental approvals to resurrect exploration in Australia.

Additional gas into the domestic power market will also help Australia realise its formidable renewables potential, supporting the flexible power capacity needed as wind, solar and storage ramp up. This should be combined with major public-private partnerships to ensure increasing grid capacity and reliability. Positioning Australia as a global leader in green hydrogen depends on it.

Achieving all this will require ambitious, collaborative and innovative thinking. Strong initiatives by the federal government are needed to bring together the broad coalition of stakeholders on which Australia’s transition relies: state and local government, energy companies, utilities, importers, finance and local communities. To ensure all remain committed, barriers to investment must be brought down.