Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

The OPEC+ group fails to reach agreement as oil demand plunges

In this week's Energy Pulse, oil demand is in its steepest decline since the great financial crisis, but OPEC and its allies have been unable to agree a deal to cut production.

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

What the "big beautiful bill" means for US energy

-

Opinion

Inside the ‘crazy grid’

-

Opinion

The Big Beautiful Bill is close to passing

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

While the full economic effects of the coronavirus are still playing out, the impact on energy markets has already been dramatic. Wood Mackenzie’s current projection is that global oil demand will be down 2.7 million barrels per day (b/d) for the first quarter of 2020 compared to the same period last year. It is the sharpest drop since the height of the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Ann-Louise Hittle, Wood Mackenzie’s head of macro oils, said a longer, sustained outbreak of coronavirus threatened to hit oil demand with a double whammy, from containment measures and slowing global economic growth.

However, in the face of challenging market conditions, the OPEC+ group, made up of OPEC and its leading allies including Russia, failed to agree on concerted action to cut oil production.

Speaking after the OPEC+ meeting in Vienna broke up, Hittle said: “Today’s outcome is a psychological blow for the market, as the steep plunge in oil prices shows.

“The market is now facing the spectre of unrestrained production once the current OPEC+ agreement expires in March.”

She added: “A sustained bout of low oil prices will further reduce cash flow and investment into the US oil patch, causing further hits to Lower 48 production growth later this year. It takes at least six to nine months for reductions in spend to lead to lower oil production in the US Lower 48. In that time, their access to capital may be limited and their free cash flow badly hit.”

Meanwhile, the OPEC+ group could be forced to call an emergency meeting during the second quarter if oil prices continue to fall.

Coronavirus shockwaves hit refiners

Refining has been one of the industries hit hard by the coronavirus outbreak’s impact on the economy. Even before the outbreak, it was under pressure. The International Maritime Organization’s new rules for the sulphur content of marine fuels, which took effect at the start of this year, had been expected to widen the pricing differential between diesel/gas oil and high sulphur fuel oil, by boosting the demand for lower sulphur fuels. This change in the relative pricing of refined products was expected to widen the discount for heavier/sourer crudes, and the combination of these effects was expected to increase refining margins.

From late October 2019, though, hopes for those benefits started to fade. The growing demand for IMO-compliant fuel oil was met from inventories, and the OPEC+ production cut agreed in December reduced supplies of sour crudes, closing the price discount to sweet crudes. Refining margins were squeezed, and the oil majors’ downstream earnings slumped in the fourth quarter.

This year should have been better, but so far it is not turning out that way. The fall in demand for oil products is putting further pressure on refining margins, says Alan Gelder, Wood Mackenzie’s vice-president for refining, chemicals and oil markets. The global composite gross refining margin averaged US$3.60 per barrel in 2019, but is down to just US$1.70/b in the first quarter of 2020.

In a sign of the financial strains created by the economic shock from the coronavirus, banks are suspending the credit lines for some Chinese independent oil refiners, Reuters reported.

The failure of the OPEC+ group to reach agreement on a production cut is at least one silver lining for refiners under a very dark cloud, Ann-Louise Hittle said. “The sector will be hit hard by weak demand, but it is at least saved from tightening crude differentials associated with a major cut in OPEC supplies.”

GM launches its EV push

Back in the 1990s, General Motors was a pioneer in electric vehicles with its EV1. That innovation ended in failure; such a conspicuous failure, in fact, that there was a documentary made about it. Now GM is trying again, this week announcing a strategy for based on a modular platform and a new battery system called Ultium. Mark Reuss, GM’s president, said the company was “on the cusp of delivering a profitable EV business that can satisfy millions of customers”.

The battery system is critical to the strategy. GM has a joint venture with LG Chem to produce Ultium batteries, using a proprietary technology that requires less cobalt than in the standard lithium-ion chemistry. GM says that the JV aims to get battery costs down to $100 per kilowatt hour (kWh), often seen as the level that could make EVs cost competitive with internal combustion engine cars. The battery is being seen as a potential “Tesla killer”.

Meanwhile, Tesla is reported to be close to launching its own plans for mass production of battery cells at $100/kWh at its “battery day”, expected next month.

While $100/kWh batteries certainly look achievable, they may be a few years off yet, cautioned Milan Thakore, a senior research analyst at Wood Mackenzie. Prices today average around $140/kWh. GM’s partnership with LG Chem would certainly help reduce costs, “but getting below US$100/kWh any time soon will be impressive,” Thakore said. “We believe it will be several years until automakers can purchase battery packs at the US$100/kWh mark. Even then, the cost might still be too high for some automakers’ mass-market EVs.”

Oliver Blume, chief executive of Porsche, told the Financial Times this week that he thought the cost of lithium-ion batteries for EVs was unlikely to drop for at least five years. “I don’t expect decreasing costs in batteries, because there is a big demand and we still have a bottleneck in production capacities,” he said.

ExxonMobil and Chevron set out their plans for growth

The two largest US oil and gas companies usually schedule their annual presentations to analysts and investors in the same week, creating a good opportunity to compare them side-by-side. They did it again this week, pointing out some common themes, including their shared emphasis on growth in the Permian basin.

Chevron went first, and its presentation on Tuesday focused on a combination of returning cash to shareholders and increasing production over the long term. The cash distribution target for dividends and share buybacks over five years is US$75 billion to $80 billion: more than 40% of the company’s market capitalisation. That would be much more lavish cash distribution rate than in the past. In the five years 2010-14, Chevron’s cash pay-outs totalled US$54 billion, and that was in a period when the Brent crude price averaged about US$102 a barrel.

ExxonMobil’s presentation, two days later, similarly pointed to long-term growth. Darren Woods, chief executive, emphasised the value of sticking to the company’s capital spending plans in difficult conditions, saying it was “leaning in to this market when others have pulled back”. It is cutting the number of rigs it has active in the Permian and slowing the pace of production growth there, but it is still aiming at the same objective of 1 million barrels of oil equivalent per day by 2024.

In brief

The European Commission has proposed the EU’s first ever climate law, intended to set a framework for cutting net carbon emissions to zero by 2050. The law would put in place measure to implement the “European Green Deal” launched last year.

Carbon dioxide emissions in the UK, now outside the EU, dropped 2.9% last year to their lowest level since 1888.

The UK’s chief climate adviser has urged oil and gas companies to lead investment in clean energy technologies rather than waiting for government subsidies.

A gas-fired power plant in upstate New York is reportedly mining Bitcoin worth an average of $50,000 per day.

And finally: Ronan Keating’s many hits as a member of Boyzone and as a solo artist may be slipping into pop history, but he was back in the news this week because of his observations on the economic impact of the coronavirus. He posted on his social media accounts a photo of ships outside the port of Singapore, with a caption explaining that they were “not allowed to dock because of the virus”.

He still has a public profile, and his comments caused a bit of a stir, but he was wrong: the crowded waterway actually just showed normal traffic at the busy port. The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore posted a sharp response, observing that “to date, no cargo vessel has been turned away due to the Covid-19 outbreak”. Keating later deleted his posts.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Future energy: Carbon capture and storage

Will Nichols — Why 2020 is the crunch year for climate risk reporting

Nick Butler — Look beyond European oil majors’ steps to net zero

John Kemp — China's internal not export market matters more for the world economy

Jason Bordoff — A flaring tax can end this wasteful and damaging practice

Julia Pyper — Decarb Madness: How would you build a policy bracket to decarbonise the power sector?

Henry Mance — Will the coronavirus change how we live?

Eric Holthaus — No, the coronavirus is not good for the climate

Christian Roselund — Transition in electricity: 2020 update

Quote of the week

“We welcome a lower-carbon future, and we intend to be a big player in a lower carbon energy future… The challenge is: how do you invest in things that are good for the environment and good for shareholders.”— Michael Wirth, Chevron’s chief executive, said at the company’s annual presentation to analysts this week that it aimed to invest more in low carbon energy, and was looking for profitable investments in renewables. He cited a couple of ideas that Chevron is working on: using bio feedstocks in a refinery in California, and producing renewable natural gas from waste, but promised to be as “disciplined” in investing in renewables as in the rest of the business.

Chart of the week

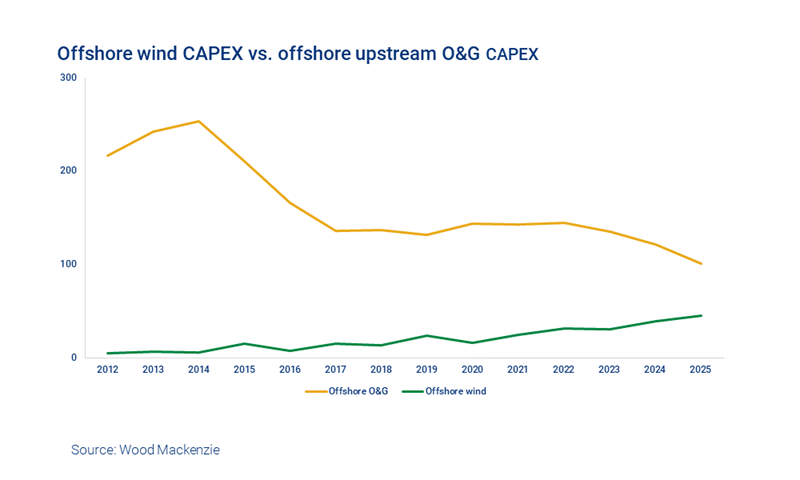

This very striking chart comes from an opinion article on offshore wind by WoodMac’s Søren Lassen and Mhairidh Evans. The yellow line shows actual and expected capital spending in offshore oil and gas, while the green line shows capital spending in offshore wind. By 2025, oil and gas is still set to be well ahead of wind, but the gap is expected to have closed sharply. In 2012, spending on offshore oil and gas was more than 30 times greater than spending on offshore wind. By 2025, it might be only a little over twice as large. It no longer seems impossible that the lines could eventually cross over.

How to get Energy Pulse

Energy Pulse is Ed Crooks' weekly column, published by Wood Mackenzie every Friday. Here's how to get Energy Pulse:

- Follow us on social media @WoodMackenzie on Twitter or Wood Mackenzie on LinkedIn

- Fill in the form at the top of this page and we'll send you an email when the latest issue goes live

- Bookmark this page to have access to the full archive of Energy Pulse