Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Energy transition – reset required

Policy must keep the drive on long-term goals

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

How can the world get through the current energy crisis to deliver on its net zero pledges and maintain reliable, affordable energy? The coordinated global response to geopolitical and energy market turmoil during the 1970s, and more recently to the Covid health crisis, offers hope it might be achievable – where there’s a will, there’s a way. Prakash Sharma, Vice President Research, and David Brown, Director, Energy Transition Practice, Research, drew five key messages from our 2022 Energy Outlook ahead of our Global Summits (see below). I asked them for their latest thoughts.

Energy security and price affordability drive the next phase of the transition

War has catapulted energy security and affordability to the very top of the political agenda. The threat of disruption of Russian energy supplies has pushed the price of oil, coal, natural gas and power higher; the latter two through the roof.

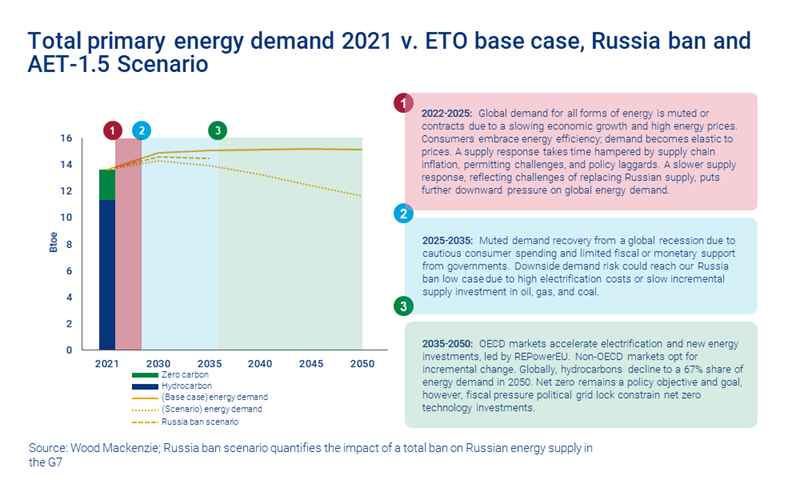

Economic and political necessity are forcing governments back to fossil fuels, complicating the progress of decarbonisation for the next 5 to 10 years. We expect fossil fuels’ share to decline from 80% in 2021 to 66% by 2050, but most of the decline happens post-2030. This means the world stays on a 2.5°C warming trajectory.

A rapid transition to a 1.5°C world needs a structural shift to lower carbon fuels and feedstock. Governments, as well as investors and consumers, must double down on low-carbon technologies that lower prices, provide energy security and maximise existing generation assets.

The fundamentals for decarbonisation remain in place

Many of these technologies are already gaining a foothold, among them low-carbon hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, next-generation nuclear, geothermal and advanced battery chemistries. Costs for some will be lower than fossil fuels within a decade.

The US leads in carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), contributing 28% to total announced capacity. The scaling up of CCUS for post-combustion emissions globally will be critical to reducing Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions in power generation and hard-to-abate sectors.

In Asia, co-firing ammonia in a coal plant provides a dispatchable low-carbon power generation alternative and will extend the life of an existing asset for many years to come.

In Europe, green hydrogen is at the centre of decarbonisation plans for multiple industries. Just last week, Germany and Canada signed an ambitious hydrogen supply agreement that targets first shipments in 2025. More such deals will help diversify Europe’s energy supply away from imported natural gas, drive down costs and unlock hydrogen demand in new applications.

Resolving supply chain challenges will take time

Critical minerals and components to produce low-carbon technologies are caught up in global supply chain bottlenecks. High commodity prices and the rising cost of capital add to inflationary pressures, compounding the challenges. Costs have increased three to five times across energy and agriculture commodities since January 2020.

The world is waking up to China’s domination in supply chains critical to the energy transition, both in raw materials and manufacturing. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) offers larger incentives for electric vehicles (EVs) to battery raw material producers. The US aims to create an alternative market domestically for battery supply chains and low-carbon hydrogen, which will benefit other OECD markets, too.

But it won’t happen overnight. Reshoring the EV supply chains to meet IRA-incentive rules could take up to 10 years.

Bolder policy is emerging to guide capital allocation

Fossil fuel producers are generating record free cash flow on the back of high prices – we estimate the oil and gas sector will generate US$450 billion surplus cash flow in 2022, assuming US$100/bbl Brent. Capital allocation has largely favoured strengthening balance sheets and higher shareholder distributions.

Energy and mining companies will also have to adapt to ever-tightening ESG criteria. Signatories to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) have committed to investing in assets based on the goals of the Paris Agreement. The 450 financial institutions GFANZ represents have combined assets of US$130 trillion and wield huge influence.

Policy has to guide capital flows, and that is starting to happen everywhere. European governments have responded to the loss of Russian volumes to deliver new gas supply infrastructure in the next few years; RePowerEU simultaneously doubles down on the rollout of renewables and electrification. Japan and South Korea are keen to restart safe reactors and invest in next-generation nuclear power generation technologies. Clear demand-side targets are a major channel through which investment will flow.

An inclusive transition needs crisis management skills and coordinated policies

Delivering a secure, affordable and clean energy system will be harder still in the current environment. Russia’s war on Ukraine and the resulting supply crunch has exposed the weaknesses of energy policymaking. It defies belief that affluent economies in Europe, Japan and perhaps others may have to resort to rationing energy supplies this winter.

Coordinated and targeted policies will be essential to get though the crisis. In the short term, governments are stepping in to support consumers. The UK Government outlined a plan for £130 billion to cap average energy bills at £2,500 a year per family; others will do similar. But these are stop-gap measures. Low-cost, low-carbon energy is the end; carbon pricing will be a key tool to create a level playing field and direct capital to climate-friendly technologies such as hydrogen, CCUS, geothermal and SMR nuclear.