Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Exploration’s star is rising

High-impact wells can help replace Russian oil and gas volumes

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

Exploration was performing even before the recent rise in the oil price. But with capital markets indifferent at best to the higher risk end of upstream investment, it has paid to keep wildcatting under the radar.

Conventional exploration today is focused on low cost, low carbon barrels that can be monetised swiftly. We call these advantaged resources. Many explorers though have been forced by a lack of finance and dwindling opportunities into drilling near-field, short-cycle, lower potential value prospects. This high risk for modest reward equation has led to some giving up entirely.

High-impact exploration is the exclusive reserve of the Majors and a handful of leading NOCs. Only these companies have the appetite and capabilities to drill and develop oil and gas fields in the deep water where most of the new giant resources are to be found. These frontier play-opening and play-extension wells are usually much more expensive to drill. The size of the discoveries, though, often brings great economies of scale. They also deliver by far the most value.

High-impact strategies have been vindicated by an impressive harvest of giant discoveries. Dr Andrew Latham, VP Research, thinks the improved performance isn’t just helping to rebuild exploration’s credibility as a value proposition. It’s positioning exploration to play a role in sourcing alternatives to Russian exports of oil and gas.

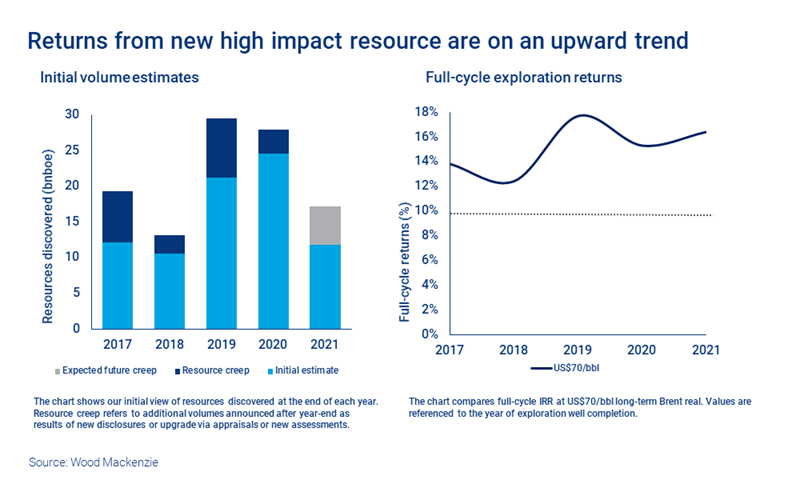

First, let’s quantify the improved performance. The 12 billion boe of resource discovered in 2021 (split evenly between oil and gas) didn’t make for a standout year but spend was low – 75% below the 2014 peak and 25% below 2019’s. Adjusting for reserve creep, last year’s resource discovered will be close to the five-year average. Over half of it (55%) already looks commercial, creating value of US$15 billion and returns of 16% (at a US$70/bbl long-term oil price). More will be commercialised in time.

High-impact exploration accounted for almost all of the value created in 2021. Seven giant discoveries were made in a variety of basins, plays and countries – Russia, Azerbaijan (BP), Cote d’Ivoire (Eni), Guyana (ExxonMobil), Mexico (Pemex) and Turkey (TPAO).

High-impact wells are delivering spectacular results again in 2022, including a major new deepwater play-opener in Namibia. TotalEnergies’ monster Venus oil field has 3 billion boe recoverable; Shell’s Graff oil field 700 million boe (a bold step-out near completion holds the prospect of a very sizeable increase). Qatar Energy partners in both discoveries, one of an increasing number of NOCs active in international exploration.

Namibia has the potential to follow in Guyana’s footsteps. ExxonMobil’s two new finds in Guyana’s prolific Stabroek block this year have lifted reserves to well over 10 billion boe. Petrobras and BP have made an oil discovery in the last few days on a prospect in Brazil.

Second, companies committed to drilling the discovery wells because they met stringent commercial criteria. These include conservative price assumptions and project payback within 10 to 12 years. Operators tend to favour oil-prone prospects because the payback is quicker.

In Wood Mackenzie’s 1.5 °C accelerated energy transition scenario, AET-1.5, oil demand falls from 100 million b/d today to 70 million b/d in 2035 and 35 million b/d in 2050. Even in this scenario, low-cost, low carbon-intensive oil and gas will displace high-cost production from the supply stack.

We estimate that the commercial discoveries made in 2021 and so far in 2022 could collectively deliver over 1 million b/d of oil production alone at peak around 2030. And it could be much higher – big discoveries tend to get bigger over time. Gas production will be similar, but the peak later.

Third, the world will need more oil and gas from high-impact exploration. Our downside scenario projects Russian oil production to be 2 million b/d lower in 2030 than our pre-crisis forecasts, while Europe is looking to cease imports of Russian gas completely.

We don’t expect substantive changes to the core upstream strategies that evolved before the crisis. But the small group of IOCs and NOCs that have kept faith in exploration will be emboldened by recent successes and the unexpected twist to events the war in Ukraine has brought. More capital may come exploration’s way, and more of it might be targeted at gas.

We may also see explorers a little less reticent about their exploration strategies and successes. And all of this will give pause for thought to those considering a rapid wind-down of exploration.