The prize for China from decarbonisation

A low-carbon economy holds the promise of greater control over its energy

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

China targeting net-zero emissions by 2060 last September was a big moment, providing a significant boost to the gathering global effort to tackle climate change. But China’s motives for decarbonising go well beyond climate. I asked Gavin Thompson, Vice Chair Asia Pacific, and his Beijing-based colleagues Miaoru Huang and Yanting Zhou, authors of our March Horizons, about the prize China sees in overhauling an energy- and carbon-intensive economy.

Why is China embracing decarbonisation with such zeal?

It’s important to emphasise that China’s pathway to decarbonisation is a long-distance journey. And while the latest five-year plan arguably disappointed on near-term decarbonisation targets, the real focus for China’s leadership is on what can be achieved out to 2060.

Much of the motivation has come from a domestic economy that increasingly depends on imported commodities. China hasn’t been self-sufficient in oil for 30 years. Demand will touch 15 million b/d later this year, close to the 2019 high, and 75% of those barrels will be imported. It’s much the same story for most other energy and mined commodities.

From a strategic perspective, China views decarbonisation through two distinct prisms – domestic and global. On the one hand, it’s a golden opportunity for China to lessen its dependence on the old staples, and, on the other, gain far greater control over the energy technologies and the supply chains the world needs to decarbonise.

What’s China’s plan?

The 14th five-year plan last month is the roadmap to a more efficient and, ultimately, lower carbon energy future. An entire chapter of the plan – ‘Establishing a Modern Energy System’ – is intended to support greater energy efficiency, a bigger role for natural gas and, of course, renewables and electric vehicles. Equally as significant, the plan lays out how the economy will be services- and technology-led in future rather than the carbon-intensive industries of today.

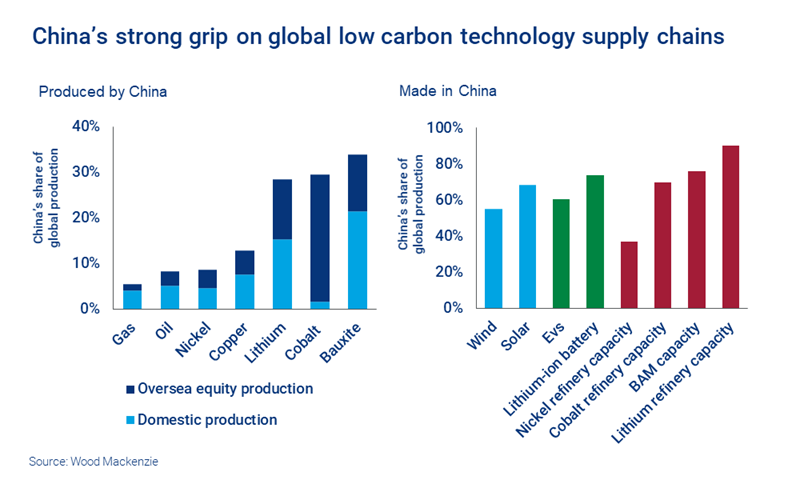

Electrification will be central to decarbonisation and we estimate demand could rise by as much as 75% by 2050. China can build the power generation capacity – it’s already the global leader in manufacturing wind turbines and solar panels. It’s also a leader in electric vehicles – half of the world’s EVs are produced in China; and it’s a major centre for battery manufacturing. China has a strong platform in these proven, commercial technologies which will lead the charge in the early decades of decarbonisation.

Can China access the commodities it will need?

Up to a point. China has spent the last decade establishing a supply chain in battery raw materials. Chinese companies, freer from ESG constraints than western peers, have secured ownership and access to cobalt resources in the Democratic Republic of Congo, lithium reserves in Chile and Indonesia nickel mines. It also has an abundance of domestic bauxite mining to supply aluminium. But there are limits to China’s self-reliance – it already imports 85% of its copper supply and, as demand takes off with the transition, it will rely even more on foreign miners.

Will China’s metals position make life awkward for others?

Its strength in battery raw materials poses a challenge. China’s not the only country with ambitious decarbonisation plans. The EU and US economic stimulus packages have flagged massive investment in the entire low-carbon value chain. European and US companies, too, will want to ramp up their domestic manufacturing of EVs and batteries to industrial scale. With China in control, tying in the battery raw materials supply chains is the hard part.

What options do other countries have to access metals supply chains?

There are a few. First, encouraging tougher ESG standards would level the playing field in the DRC and other mining countries and open the door to more diverse international investment. Second, investing in new technologies – battery chemistries including solid state batteries. Third, increasing recycling rates - today’s 35% needs to at least double.

Is decarbonisation all about ‘go-it-alone’?

Far from it, co-operation will play an important part. Decarbonisation is a global challenge, not about any single country or region, whether China, the US or Europe. China, for all its strengths, doesn’t hold all the cards. President Xi’s attendance at the US-hosted Leaders’ Summit on Climate, which began yesterday, despite rising tensions with the US, recognises that co-operation is central to addressing climate change. We can expect China to be a key player at COP26 in Glasgow.

Forty years ago, China looked to the IOCs for technical expertise and capital to help unlock its offshore oil and gas reserves. Similar partnerships with international businesses would reduce the risks of commercialising the technologies, such as hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, that will be critical to delivering net-zero targets.

Explore this topic in more detail

China’s path to net zero will be one of the key themes of our upcoming Power & Renewables APAC Virtual Conference.

This virtual event will gather perspectives from leading industry stakeholders including the Development Bank of Japan, RWE, Amplus Solar, BayWa r.e., Dai-Ichi Life Insurance, Société Générale, along with our own energy transition experts for the Asia Pacific region.