Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

US greenhouse gas emissions are falling, but not fast enough

Rise in emissions in 2022 likely to be short-lived, but the long-term trend is for only gradual decline

8 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

US greenhouse gas emissions rose in 2022, for the second year in succession. It was a step in the wrong direction for the Biden administration, which is aiming for a cut in emissions of at least 50% from 2005 levels by 2030, on its intended path to net zero in 2050. Environmental commentators were despondent. “Despite some recent progress on climate policy, such as the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the country is still on a reckless path,” the Los Angeles Times argued.

In the detail of the data, and in Wood Mackenzie’s projections for the outlook to 2050, there is better news. US greenhouse gas emissions are on course to start falling soon, and to decline steadily over the coming decades. But the administration’s emissions goals still look very demanding, and on the basis of current policy positions they are unlikely to be met.

The uptick in emissions last year reflected the continuing rebound in the economy from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020-21. The recovery in travel for both business and leisure meant that US oil demand continued to grow, rising about 2% in 2022. Energy use in industry, and in the residential, commercial and agricultural (RCA) sectors, also continued to grow, driving up their emissions.

There was one large sector where emissions did not grow last year, however, despite increased activity: power generation. A shift away from coal and towards natural gas, wind and solar power held down emissions while total generation increased. That shift, along with other long-term changes in patterns of energy consumption, is set to have a big impact on US emissions over time.

Data from Wood Mackenzie’s Energy Transition Tool show that US emissions from coal use have already dropped by 45% since 2000. In our base case forecast, they are expected to drop by a further 55% by 2030, and then to fall almost to nothing by 2040.

In the transport sector, emissions have until now been highly resilient. US emissions from transport were roughly the same in 2022 as they were in 2000. But as engines become more efficient and electric vehicles take a growing share of the US market, helped by generous tax breaks, that trend line is also expected to start heading downwards. We forecast that US oil demand will rise for a couple more years and then hit a plateau in the mid-2020s, before starting to decline around the end of the decade.

By 2050, we expect US emissions from oil to be down about 40% from their current levels.

Put all these trends together, along with the industrial and RCA sectors, where the technological pathways to lower emissions are generally less well-established, and we project a decline of about 10% in total US emissions between 2022 and 2030.

In part, that outlook reflects factors that are not affected much by government policy, such as the availability of abundant low-cost natural gas supplies that have helped cut coal’s share of the power generation mix. But some policy measures are having a significant impact: in particular the Inflation Reduction Act, passed last year, which is giving a huge boost to investment in renewable energy and storage.

The problem for the Biden administration is that even after the IRA and a range of other measures, the expected pace of long-term decline in US emissions does not look fast enough to get to the target reduction of 50%-plus from 2005 levels by 2030, or to net zero by 2050.

David Brown, Wood Mackenzie’s director for the energy transition, said: “The Inflation Reduction Act will act as a strong tailwind for lower carbon investments. But even so, the United States is on course to fall short of its net zero goals. A step-up in policy support, streamlining permitting, and larger developments for materials supply chains are what's required to put the country on a net zero pathway.”

As the administration discusses climate strategy with other countries, and seeks to encourage them to set and keep to ambitious goals of their own, it will probably need to do more in terms of setting policies to cut emissions.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos this week, John Kerry, President Joe Biden’s climate envoy, argued that the world was not acting fast enough on climate change.

“I’m convinced we will get to a low-carbon, no-carbon economy. We’re going to get there because we have to,” he said. “I am not convinced we’re going to get there in time to do what the scientists said, which is avoid the worst consequences of the crisis.”

His counterparts could argue that it is a charge that could very easily be leveled at his own country as well.

In brief

A new Wood Mackenzie report this week predicted a “boom time for US renewables manufacturers” over the coming decade, thanks to the generous incentives offered in the Inflation Reduction Act passed last year. The expected impact of the IRA has caused consternation in some countries that aim to compete against the US in international markets for low-energy, and this week the EU announced that it planned a package of measures in response.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, said: “The aim will be to focus investment on strategic projects along the entire supply chain. We will especially look at how to simplify and fast-track permitting for new clean tech production sites. We need to create a regulatory environment that allows us to scale up fast.”

Meanwhile, the EU is still in negotiations with the US to see if some of the European concerns about the new law can be eased.

Oil and gas companies’ upstream investment is continuing to rise, but is still not yet returning to the levels seen immediately before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. The 55 companies that have disclosed upstream budgets thus far plan to spend a combined US$116 billion, 15% more than estimates for 2022, Wood Mackenzie analysts say. But that total is still about 10% below their capital spending in 2019.

The Environmental Defense Fund, a group that often aims to work with businesses rather than against them to advance its agenda, has published a list of “climate principles for oil and gas mergers and acquisitions”. The principles are intended to address an issue that is becoming increasingly apparent as some leading oil and gas companies have been selling assets to cut their emissions. As the EDF puts it: “Such transactions may help companies reach their own emissions reduction targets, but they do not contribute to global greenhouse gas emissions reduction — and may even result in overall emissions going up.” The EDF is urging companies to adopt its M&A principles if they are “looking to show leadership on climate”.

Shell is buying the US EV charging company Volta for US$169 million. Shell has set a target of operating over 500,000 charge points worldwide by 2025.

Britishvolt, a company that had aimed to play a central role in the electrification of road transport in the UK by building a large factory to make batteries for EVs, has gone into administration. Most of its 232 staff were made redundant with immediate effect.

Other views

Daniel Liu — Boom time: What the Inflation Reduction Act means for US renewables manufacturers

Simon Flowers — Transforming the US EV battery supply chain

Massimo Di Odoardo — Gas and LNG: Predictions for 2023

Akif Chaudhry and Norman Valentine — Mixed signals for power and renewables in 2023

Joe Daniel — How utilities can save customers billions of dollars

Ketan Joshi — The dawn of gas stove denialism

Derek Brower and Myles McCormick — What the end of the US shale revolution would mean for the world

Quote of the week

“Our transformation towards a climate neutral economy, the fundamental task of our century, is currently taking on an entirely new dynamic. Not in spite of, but because of, the Russian war and the resulting pressure on us Europeans to change. Whether you are a business leader or a climate activist, a security policy specialist or an investor, it is now crystal clear to each and every one of us that the future belongs solely to renewables. For cost reasons, for environmental reasons, for security reasons. And because in the long run renewables promise the best returns.” — Olaf Scholz, Germany’s chancellor, used a speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos to set out his uncompromising views on the future of energy.

Chart of the week

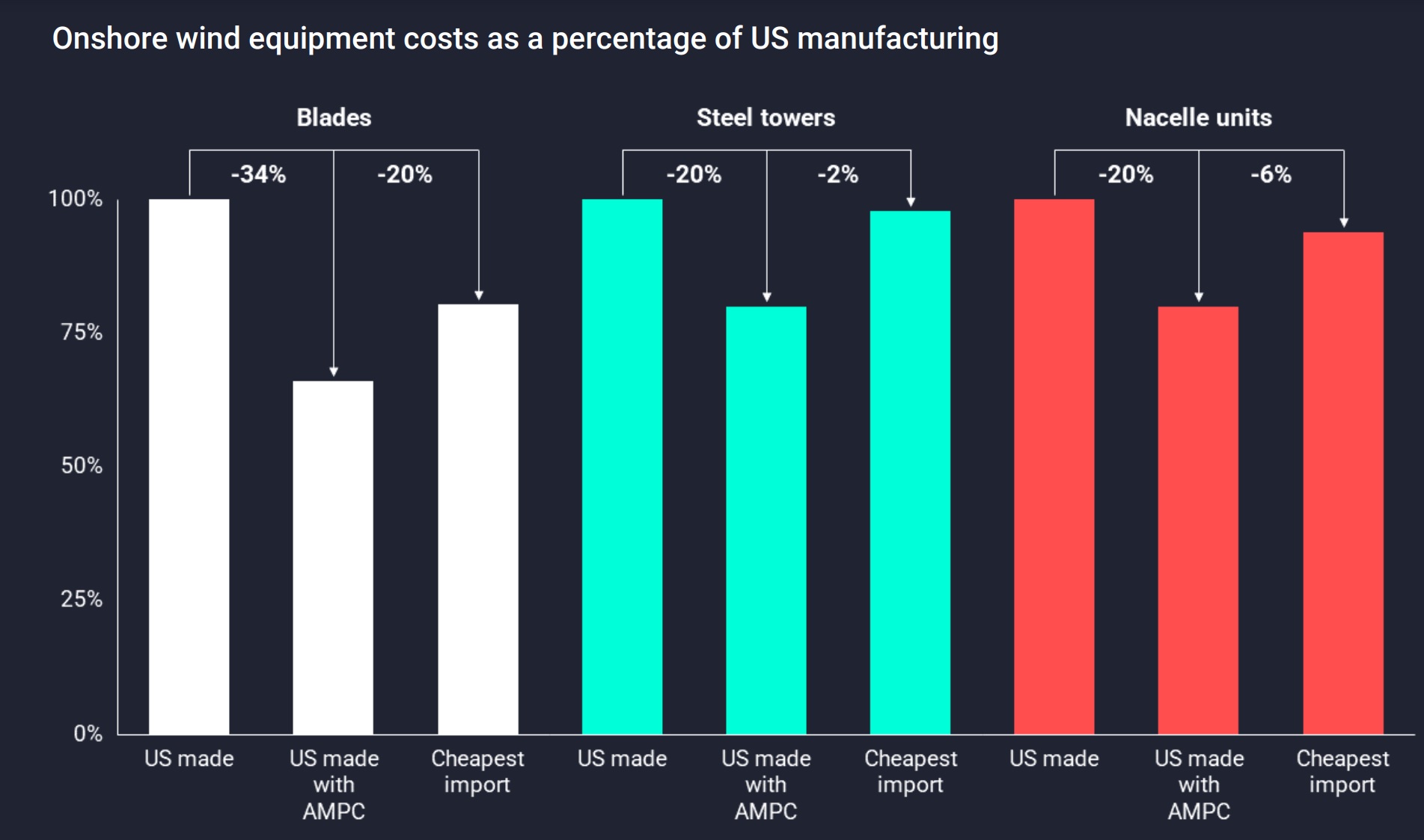

This is one of many fascinating charts in Wood Mackenzie’s major new report: Boom time — What the Inflation Reduction Act means for US renewables manufacturers. It shows the dramatic impact that the incentives in the new law, in this case the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit (AMPC), will have on decisions about where to locate manufacturing capacity for low-carbon energy equipment. The way to read it is to look at each group of three bars, each of which represents a key component for an onshore wind turbine. Blades are in white, steel towers are in green and nacelle units in red. In each group of three, the left-hand bar represents the cost of US production before the Inflation Reduction Act, the right-hand bar represents the lowest-cost imports that are available in the US. The car in the middle shows US manufacturing costs once the AMPC is in place. You can see that for all three types of component, US manufacturing supported by the tax credit now seems to have lower costs than the most competitive imports. Charts like this make it clear why several other countries have been concerned about the impact of the new incentives on international competition. There are several other good examples in the full report.