Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

UK energy exports and fracking: aspiration or pipe dream?

UK Prime Minister Liz Truss lifts the ban on hydraulic fracturing to hit 2040 export targets

3 minute read

Fraser McKay

Head of Upstream Analysis

Fraser McKay

Head of Upstream Analysis

As head of upstream research, Fraser maximises the quality and impact of our analysis of key global upstream themes.

Latest articles by Fraser

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: diverging development strategies in Latin America, investment at risk in Africa, and Kazakhstan supply tensions explained

-

Opinion

Is oil price volatility a threat to upstream production, investment and supply chains?

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: UK fiscal changes and an Asia-Pacific licence bonanza

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: the global sanctions slump, grappling with gas and potential US tailwinds

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: the global sanctions slump, grappling with gas and potential US tailwinds

-

The Edge

Why upstream companies might break their capital discipline rules

Neivan Boroujerdi

Director, Corporate Research

Neivan Boroujerdi

Director, Corporate Research

Neivan leads Wood Mackenzie's global corporate NOC coverage.

Latest articles by Neivan

-

The Edge

The complexity of capital allocation for oil and gas companies

-

Opinion

Ten key considerations for oil & gas 2025 planning

-

Opinion

ADNOC doubles net hydrogen production through stake in ExxonMobil’s Baytown project

-

Opinion

ADNOC acquires stake in Rovuma LNG from Galp

-

Opinion

Benchmarking the Middle East NOCs against the supermajors

-

The Edge

How and why big oil is strengthening its oil and gas exposure

Greg Roddick

Principal Analyst, Upstream

Greg Roddick

Principal Analyst, Upstream

Greg has almost 15 years of industry experience, focused on corporate strategy, fiscal modelling and economic analysis.

Latest articles by Greg

-

Opinion

North Sea upstream: 5 things to look for in 2025

-

Opinion

Benchmarking 2023’s upstream FIDs

-

Opinion

Has Norway’s oil and gas tax stimulus been a success?

-

Opinion

UK energy exports and fracking: aspiration or pipe dream?

The UK has announced plans to become a net energy exporter by 2040. This includes lifting the 2019 ban on hydraulic fracturing in unconventional shale plays in England and offering 100 new North Sea exploration licenses. The government suggested shale gas production could start within six months if local communities support development.

Download our insight below.

The announcements came as part of a broader response to the UK’s energy crisis, which included price caps and a reaffirmation of the UK’s adherence to the Paris Agreement. The government remains committed to the 2050 net zero target – though the plan for achieving this will be reviewed.

We delve into what we know of the new prime minister’s plans and looked at how they might measure up under various energy demand scenarios.

Shale faces too many headwinds to make an immediate impact

While there are very few details on the UK’s net export plan, we believe shale gas faces too many political, technical, economic and funding headwinds to make a material impact this decade.

Removing the “fracking ban” is a step forward for shale proponents, but for new supply to materialise, E&Ps would need to commit to exploration and appraisal work, and a shale oilfield service (OFS) sector would need to emerge.

Even if drilling were to start straight away, 2023 volumes would be negligible relative to immediate energy issues. With only a handful of wells drilled to date, the exploration and appraisal process could easily run into the latter half of the decade.

As with all shale basins, the UK’s gas initially in-place (GIIP) volumes appear vast. But economically recoverable gas is the key indicator. Purely for indicative reference (making technical or economic analogies at this stage would be misleading) the UK’s highest-profile Bowland-Hodder upper formation’s GIIP is similar in scale to the Fayetteville, a mature shale play in the US Lower 48.

The Fayetteville is nearly fully developed with over 6,500 wells to-date, and 10 tcf of cumulative production. Replicating this in the UK, from a standing start, even assuming similar or better well performance (which is as-yet unproven) is a gargantuan challenge.

The ban was just one of the commercial hurdles

Despite the ongoing energy crisis, shale developments will face even higher levels of public scrutiny than offshore. Incentives will need to be sufficient to align all stakeholders. But hydraulic fracturing has proven to be a highly contentious issue in the UK and even the ongoing energy crisis will not be enough to galvanise positive public opinion.

Could offshore be part of the solution?

In the last licence round held in 2019, 113 licenses were granted, though no wells were committed by the 65 companies which participated. New licensing was paused in 2020 as part of a review into the compatibility with the UK’s 2050 net-zero goals set out in 2019.

A ‘climate compatibility checkpoint’ test must pass before the round can take place, which may limit the viability of some prospects on offer.

Exploration still has a role to play in the UKCS, but drilling activity is at historic lows, The addition of new acreage is unlikely to reverse that trend significantly.

Download out insight to read our views on the potential for a new offshore licensing round.

Self-sufficiency will require a significant drop in oil demand

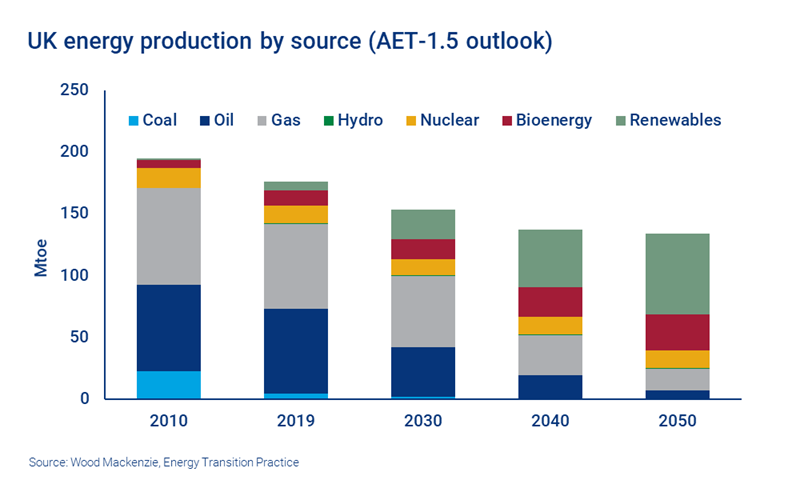

It is plausible that the UK could become self-sufficient in net oil, but only if a) demand is driven down rapidly by the electrification of transport and other measures needed to reach our Accelerated Energy Transition 1.5 °C scenario (AET-1.5), and b) supply reaches our high-case scenario.

Achieving self-sufficiency in gas is not achievable, even by 2040. Even with demand falling in line with AET-1.5 and production reaching our high case, the UK will remain a net importer of gas.

Renewables, hydrogen, carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS), electrification and efficiency are the most critical components in net-zero and self-sufficiency ambitions. As the plan is fleshed out over the next two months, there needs to be clarity from the government on incentivising and accelerating capital allocation into these vital areas. Doing so would take the UK closer to its ambition of becoming a net energy exporter.