Get this complimentary article series in your inbox

1 minute read

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Latest articles by Julian

-

Opinion

Metals investment: the darkest hour is just before the dawn

-

Opinion

Ebook | How can the Super Region enable the energy transition?

-

The Edge

Can battery innovation accelerate the energy transition?

-

Featured

Have miners missed the boat to invest and get ahead of the energy transition?

-

Featured

Why the energy transition will be powered by metals

-

Featured

Could Big Energy and miners join forces to deliver a faster transition?

Convention has it that inflation is good for commodities, since it goes hand in hand with strong economic activity that increases demand. This leads to higher prices as marginal supply costs are higher and supply struggles to keep up.

The benefits can, however, be transient. Higher inflation ultimately leads to rising interest rates, which dampen down economic activity. In addition, there’s a strong inverse correlation between the US dollar and commodity prices. At a simplistic level, strong US activity pushes up commodity prices. This drives inflation, which begets higher US interest rates, which then dampens down demand.

With inflation at multi-decade highs, there’s little debate about whether interest rates will rise; it’s about when, how much and how often. However, notwithstanding the potential implications of this for commodity demand and prices, for now, market dynamics across the mined commodity space are broadly price supportive. That begs a different question: with energy transition demand for mined commodities exploding, could commodity price ‘greenflation’ put up a roadblock for EVs?

The EV sales explosion is set to continue

My colleagues and I have waxed lyrical about the transformative demand for mined commodities from metals-intensive EVs. Recently, we upgraded our forecasts for EV penetration to reflect the astonishing growth in sales during 2021. From just under 9% of the global total in 2021, we now expect battery electric vehicle (BEV) and plug-in hybrid (PHEV) passenger car sales to double over the next five years. BEV/PHEV commercial vehicle sales will experience similar growth, rising from 6% of total sales in 2021 to 13% in 2026.

In volume terms this means that by 2026 BEV/PHEV vehicles will exceed 18 million units, up from 6.5 million units in 2021 – a rise of 170%. Hybrid vehicles will add a further 5.9 million units to these totals by 2026, although they are less battery metal intensive.

Rising battery costs could disrupt the EV incentive narrative

The huge growth of EVs is reliant upon several key drivers:

- government mandated EV sales targets and concomitant incentives

- societal appetite for the decarbonisation of personal transport

- increased supply chain capacity to meet demand

- EVs reaching cost parity with internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, without government incentives.

As EVs start to dominate passenger vehicle sales, the cost of incentives rises dramatically. At the same time, revenues from hydrocarbon taxes at the fuel pump drop significantly. Over the next five years incentives will undoubtedly be unravelled – in China, the world’s largest EV market, this will happen next year. EV manufacturing costs (particularly for batteries) need to fall to offset reduced incentives, rising electricity costs and inevitable taxes on EVs.

There is a circularity to this narrative, in that incentives will be reduced as battery, and hence EV, costs fall. But what if battery costs continue to rise?

Is switching battery chemistry an easy solution to rising costs?

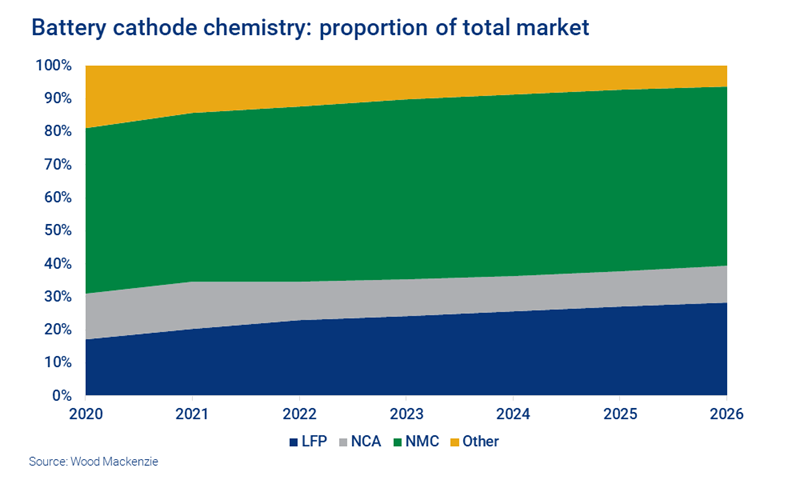

There is a get-out for EV producers: they can switch chemistries to cheaper alternatives rather than absorb higher raw materials costs. We saw a similar switch in 2020 when the Chinese authorities reduced EV incentives; this led first to a reduction in EV sales, but then to the start of a meteoric rise in the use of lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery chemistry.

Adoption was at first largely limited to the Chinese market, with Western producers favouring high-nickel ternary chemistries. However, improvements in the energy density of LFP, together with its significant cost advantage, mean it has started to take off in the West.

But there are many considerations to factor into decisions on chemistry. Whilst LFP cathodes are typically 30% cheaper than NMC 811 (nickel-manganese-cobalt) cathodes, 811 cathode energy density is 60-70% higher per kilogramme. Overall, when combined with anode to complete the cell, LFP is around 40% cheaper than an NMC 811 battery per kilogramme.

Given the cost advantages and increasing acceptance outside China, we are forecasting that LFP cathode chemistry’s global market share will rise from 20% in 2021 to 28% by 2026.

Battery costs: a complex interplay of factors

Analysis of battery costs is fraught with difficulty and based on myriad assumptions around multiple factors. As well as battery chemistry, these include EV build rates, supply chain capacity, manufacturing costs and of course commodity prices. On chemistry we have seen how fickle the market is with the rise and rise of LFP, which was driven by lower manufacturing costs than NMC.

Received wisdom is that battery costs will fall as scale and technology drive them down. For EVs to reach parity with ICE vehicles without subsidies, battery packs need to cost below US$100 per kilowatt hour (US$100/KWh). Our battery pack model indicates that delivered battery pack costs averaged US$120/KWh in 2021, with NMC batteries in the US$140/KWh range and LFP batteries around the US$100/KWh level. Despite rising prices for some battery raw materials, increased use of LFP battery chemistries and more efficient manufacturing means average battery costs are projected to fall below US$100/KWh by 2025.

EV economics are increasingly sensitive to commodity prices.

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Latest articles by Julian

-

Opinion

Metals investment: the darkest hour is just before the dawn

-

Opinion

Ebook | How can the Super Region enable the energy transition?

-

The Edge

Can battery innovation accelerate the energy transition?

-

Featured

Have miners missed the boat to invest and get ahead of the energy transition?

-

Featured

Why the energy transition will be powered by metals

-

Featured

Could Big Energy and miners join forces to deliver a faster transition?

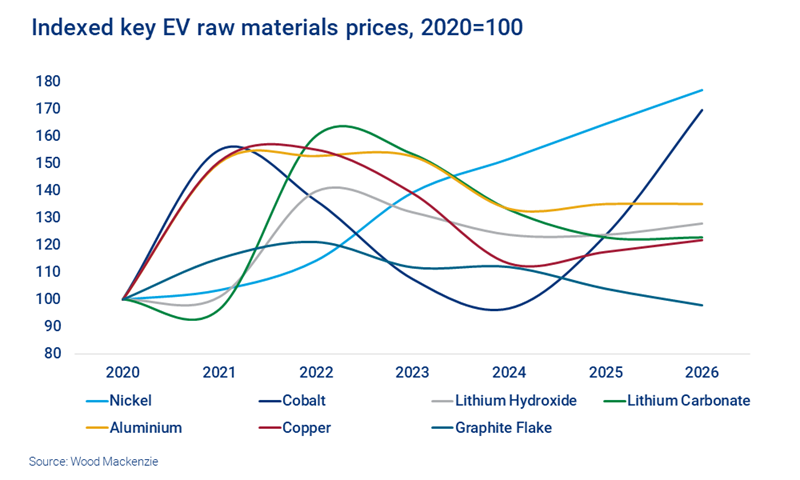

As manufacturing costs fall, the proportion of the battery pack accounted for by the materials in the pack rises. Together with the higher intensity of certain metals in EVs, this makes EV economics increasingly sensitive to commodity prices.

In the case of batteries, over the next five years, and assuming manufacturing costs decline as predicted, 60-70% of the costs of pack manufacture will be due to the price of the commodities in the pack.

Commodity price greenflation is a double-edged sword for metal producers

Commodity prices have been driven higher by economic recovery, booming demand and supply disruptions. The latter were initially coronavirus-related but are increasingly a result of energy market dynamics, in part seasonal. These factors have squeezed power market availability and driven up prices to uneconomic levels for some metals. Together with rampant growth in EV take-up, this is helping to feed ‘greenflation’ in the commodities most closely associated with EVs. Questions need to be asked about whether the assumed inexorable fall in battery pack costs will be realised.

Questions need to be asked about whether the assumed inexorable fall in battery pack costs will be realised.

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Latest articles by Julian

-

Opinion

Metals investment: the darkest hour is just before the dawn

-

Opinion

Ebook | How can the Super Region enable the energy transition?

-

The Edge

Can battery innovation accelerate the energy transition?

-

Featured

Have miners missed the boat to invest and get ahead of the energy transition?

-

Featured

Why the energy transition will be powered by metals

-

Featured

Could Big Energy and miners join forces to deliver a faster transition?

A supercycle driven by an accelerated decarbonisation pathway points to rising rather than falling prices for certain key raw materials. This, and the associated structural shortages, points to an acceleration of the trend away from the more esoteric battery chemistries. The mining industry needs to deliver the necessary ongoing supply of critical raw materials and keep prices in check. Otherwise, greenflation will force consumers to switch to proven alternatives such as LFP to remove the supply chain risk of chemistries like NMC.

As the great Stephen Hawking once said, whether this comes to pass, “only time, whatever that may be, will tell.”

Get unique views on metals and mining

This article is part of a regular series exploring opportunities and challenges in the world of metals and mining. To make sure you don't miss out, fill in the form at the top of the page to get this complimentary series in your inbox.