Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Energy demand starts on its long road to recovery

As businesses start to reopen in Europe and the US, fuel use has risen from its lows last month. But returning to pre-pandemic levels will take time

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

The last game to be played in Germany’s Bundesliga was Borussia Mönchengladbach’s 2-1 victory over FC Köln, held behind closed doors at the Borussia-Park stadium on March 11. The league had hoped to hold matches the following weekend, but postponed them as fears about the Covid-19 pandemic grew. It was a big moment for the country, and for football fans everywhere, when Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel ruled this week that the league could restart, with the first games being held on May 16.

For people around the world weary of the long weeks of lockdown, the return of German football is a hopeful sign that the world is starting to return to normal. Some European countries and many states in the US have begun relaxing their restrictions, spurred by the escalating economic cost of the lockdowns. The US lost 20.5 million jobs in April, government data showed on Friday.

This week there have been some more positive signs. As economic activity has picked up, so has energy demand. US customers bought 6.66 million barrels of gasoline per day in the week to May 1, up 11% from the week before. Demand has been rising for four consecutive weeks, although it was still down 32% from the equivalent week of 2019. Spain started this week to relax some of its restrictions, and its energy use has also been ticking up. Repsol, which reported its first quarter earnings this week, said demand had been increasing even last month. Its sales in Spain were down 75% in the first half of April, but by the second half of the month they were down about 65%. In the first few days of May, sales were down 49%.

Other indicators of activity are also on the rise. In China, as people went back to work on Wednesday after the Labour Day holiday, traffic congestion was worse than last year in Beijing and other cities, including Wuhan, where Covid-19 was first identified. Worldwide, there were about 34,000 commercial flights on Wednesday, up from about 32,000 the previous week and an average of about 28,000 a day for much of April.

As fuel demand has picked up, supply has been cut back. The production cuts agreed by the OPEC+ countries formally took effect from May 1, after a supply surge in April. Although there are indications that compliance with the agreed 9.7 million barrel a day reduction is less than 100%, it still makes a big difference to the balance of supply and demand. Meanwhile, other companies and countries around the world are also cutting output. In the US alone, announced production shut-ins will take about 866,000 b/d off the market.

Worldwide inventories of oil have been rising sharply since March, but could reach a peak in the next couple of months. In the second half of the year inventories will start to decline, Wood Mackenzie’s Macro Oils analysts expect.

As the worst of the global imbalance between oil supply and demand recedes in the rear view mirror, crude prices have been picking up. WTI, which fell close to $10 a barrel last week, ended this week at about $24 a barrel. Brent was $30.

Yet while all these indicators have been encouraging for oil prices and the industry, the return of Bundesliga football is also a warning about the slow and patchy nature of the recovery. The matches are going to be played behind closed doors — “ghost games”, as they are called — because allowing crowds was seen as too great a risk. Even as Germany announced the restart of the Bundesliga season and eased other restrictions, the number of new cases being reported rose for a third successive day.

As governments everywhere seek to revive their economies, the evidence from the US, where many states have started to ease restrictions, is that ending the lockdown is only half the story. Restoring public confidence is also critical. In Texas, the governor Greg Abbott this week issued an order allowing businesses including golf courses, hair salons and nail bars to reopen. Many others including shopping malls, restaurants, museums, and cinemas are able to open so long as they operate at no more than 25% of their legal maximum capacity. But at least initially, business in the reopened shops and restaurants has been slow.

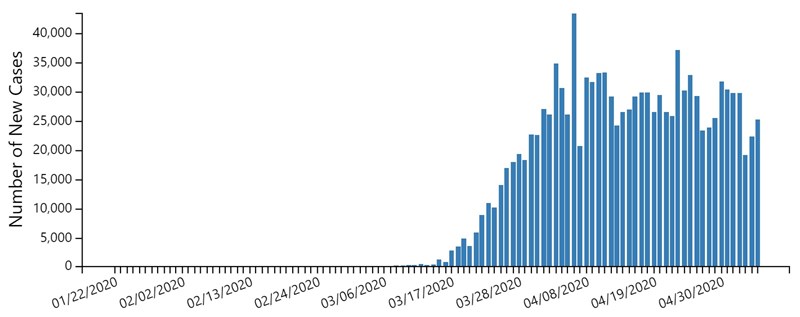

The data do not show that Covid-19 is clearly under control in the US. The numbers of new cases reported each day are down from their highest levels last month, but are not falling quickly, as this chart from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows.

For as long as the numbers of infections remain at these levels, the risk of a new surge in cases and a need for renewed lockdowns will persist. Even South Korea, one of the clear success stories in terms of controlling the virus through extensive testing and contact tracing, reported a small rise in new cases this week. It has advised nightclubs to close for a month, and may delay the reopening of schools, scheduled for next week.

The implications for energy demand are that the recovery will be gradual, and faces downside risks. Jet fuel looks like a particular weak spot. As road transport has rebounded in China, the recovery in air travel has been much more tentative. In this, as in other aspects of the recovery, China is showing the path that the rest of the world may follow. Wood Mackenzie analysts are forecasting a “multi-year” recovery in jet fuel demand, arguing that the global spread of Covid-19 “has further eroded jet fuel demand in the near-term and is expected to provide a lower ceiling for 2020 and 2021 amid fears of a ‘second wave’ in the absence of a vaccine”.

However, there are upside risks to oil demand, too. If an effective vaccine can be discovered and deployed quickly, a strong economic rebound will be possible, although not inevitable: it will still need stimulus programmes to undo the damage done during the pandemic.

For the immediate future of energy, the most important single factor is the worldwide effort to find a vaccine. That search offers the best hope of a true return to normal, rather than the uneasy imitation that we are seeing today.

In brief

Total has become the latest European oil major to declare an ambition to have “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050, by its own definition, following Repsol, BP and Royal Dutch Shell. The statement on Total’s plan was drawn up by the company working with the Climate Action 100+ group of investors, in a sign of the increasing influence over oil companies’ strategies wielded by shareholders.

Total’s definition of “net zero” includes zero emissions from its own operations and energy use — Scope 1 and 2 emissions, as they are known — and zero Scope 3 emissions from the use of its products by its customers only in Europe. For the world overall, it wants to reduce those Scope 3 emissions by cutting the carbon intensity of the energy it sells by 60%.

Patrick Pouyanné, chief executive, said in a statement that Total wanted to be “an exemplary European corporate citizen” and would offer its “active support” of the EU to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, helping other businesses to reduce their carbon footprints.

The Texas Railroad Commission decided by a 2-1 vote of the commissioners not to use its powers to compel companies in the state to cut production, putting an end to their debate over the issue. Voluntary shut-ins by operators and a sharp slowdown in well completions have already reduced output by a significant proportion of the 1 million b/d cut suggested by Ryan Sitton, the one commissioner who supported the idea.

Coal demand for power generation has been hit hard by the Covid-19 downturn, with seaborne coal prices in “near freefall”. In April, coal’s share of US power generation dropped to just 15%, down from an average of 23.5% in 2019, to David Pomerantz of the Energy and Policy Institute. The UK has gone for 28 days without burning any coal for power generation, its longest run since the electricity industry began in the 1880s, while Portugal has gone for more than 52 days without using coal.

The declines in coal consumption are being locked in by plant closures. Sweden last week closed its last coal-fired power plant two years ahead of schedule. The largest coal-fired plant in North Dakota is to close in 2022, several years earlier than expected, it was announced this week. It will be replaced by wind and gas generation.

The number of coal miners working in the US has dropped to just 43,700, the lowest since the 19th century.

Although people are in many ways desperate to get back to their lives, some changes resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic are proving quite popular. Cities including London, Paris and New York have been working on plans to take street space away from cars, to create more freedom for pedestrians and cyclists, and some of those changes may become permanent. Seattle plans to permanently close 20 miles of residential streets to traffic.

The oil crash is forcing college graduates to rethink their career plans.

Investment in renewable energy, including offshore wind, has been seen as one way to create badly-needed jobs in the US. But Ørsted has five US offshore wind projects that are threatened by possible delays as a result of the coronavirus crisis and slow progress in securing permits. The delay would be a blow to hopes of building a thriving offshore wind industry in the US over the next few years.

And finally: 100 years ago on Thursday Erle Palmer Halliburton, a US Navy veteran from Tennessee, founded the Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Company in Wilson, Oklahoma, reorganising another company he had started the previous year. Starting with “a borrowed pump, a wagon, a mule team, and a wooden mixing box,” he built a company that is now one of the world’s largest oilfield services suppliers.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Cost challenges in a $20 per barrel world

Gavin Thompson — China’s path to economic recovery remains uncertain

What crashing LNG prices mean for renewables

How will India’s extended lockdown affect the energy sector?

Julia Pyper — Are progressive climate policies a political poison pill?

Nikos Tsafos — Focus more on oil country, less on the oil industry

Steve LeVine — The harsh future of American cities

Jason Bordoff — The 2020 oil crash’s unlikely winner: Saudi Arabia

Duncan Blue — Oilfield life after the Covid-19 crash

Podcast of the week

I enjoyed being a guest on the excellent energy podcast The Interchange this week, talking about the upheavals in the oil market in recent weeks and their potential implications for the energy transition. You can listen here, or through any podcast app.

Quote of the week

“We recognize that the trust of our shareholders, and society more widely, is essential to Total remaining an attractive and reliable long-term investment. And only by remaining a world-class investment can we most effectively play our part in advancing a low carbon future.” — Patrick Pouyanné, Total’s chief executive, explained the company’s decision to adopt a “net zero” emissions ambition for 2050.

Chart of the week

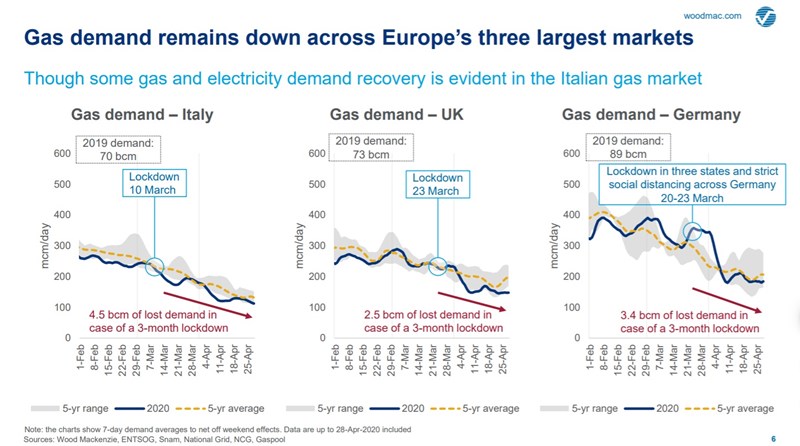

While the slump in oil demand has been the sharpest in the coronavirus-induced downturn, there has been noticeable weakness in gas demand in many countries, too. Wood Mackenzie’s global gas market analysis this week highlighted how consumption in the three largest markets in Europe has mostly been running below its previous five-year averages. There have been some signs of recovery recently: it looks as though the lowest points came during the warm weather around Easter on April 12.