Get this complimentary article series in your inbox

2 minute read

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Latest articles by Julian

-

Opinion

Metals investment: the darkest hour is just before the dawn

-

Opinion

Ebook | How can the Super Region enable the energy transition?

-

The Edge

Can battery innovation accelerate the energy transition?

-

Featured

Have miners missed the boat to invest and get ahead of the energy transition?

-

Featured

Why the energy transition will be powered by metals

-

Featured

Could Big Energy and miners join forces to deliver a faster transition?

It appears that the major mining houses are staying true to their word on maintaining capital discipline. Using Rio Tinto as a bellwether for the wider industry, on July 21 the company announced a 262% increase in its H1 2021 dividend pay-out, compared to the previous half-year period. This matched the rise in free cashflow generation over the same timeframe. Interestingly, however, given the talk of an impending decarbonisation-driven supercycle for some commodities, capital expenditure rose by a paltry 24%, to just US$3.3bn.

In light of these figures, and similar results from other miners, I question whether the industry is priming itself effectively to supply the raw materials to deliver an accelerated energy transition.

As things stand, absent a seismic shift to green hydrogen globally – and a major move towards renewables in the East – there will still be a need to invest in replacement metallurgical and thermal coal mine capacity from the late 2020s and into the 2030s, as mines deplete faster than demand. In fact, that investment will arguably need to pick up sooner rather than later. However, the key question is whether the industry at large is investing enough capital to drive the transition from the ‘carbon electron’ to the ‘green electron’ at anything close to a level that will achieve a 2 °C pathway. The simple answer is no.

Are investor constraints leaving miners’ hands tied?

Mining company finances are looking rosy, indeed they’ve arguably never looked better. Debt has been paid down (in fact Rio Tinto currently has a positive net cash balance of US$3.1bn) and firms are generating ever higher free cashflow and margins. Yet while the mining industry patently believes in the transformational demand arising from the energy transition, it remains unable (or unwilling) to greenlight sufficient projects to meet the scale of the challenge. That capex for the industry is so low must primarily come down to a lack of willingness from investors to forgo the guarantee of near-term dividends in exchange for the promise of future returns perhaps five to seven years hence.

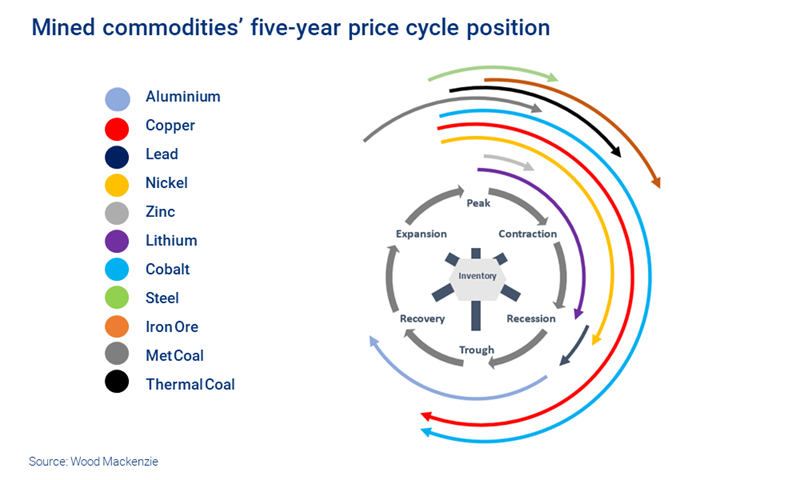

If the conditions for investors to green-light projects aren’t present now, are they likely to arise over the next five years? To assess this, we look at market dynamics and assume that prices ultimately reflect the fundamentals of supply and demand. A cursory glance at the graphic below highlights that, irrespective of strong (albeit declining) demand growth rates over the next five years, generally markets are trending to oversupply. Surpluses are a rising trend. Consequently, fundamentally justified prices will be declining over the next five years.

The spectre of cost inflation must be a concern for miners and their investors. Higher commodity prices and constrained supply chains post-pandemic are already fuelling inflation. Shortages of talent will amplify the issue at an operating level – as will wage demands when miners are making such heady profits. Together with falling prices, this points to peak margin for this cycle for most commodities being in the rear-view mirror rather than on the road ahead.

In such an environment, investors are naturally reticent to greenlight capital investment, even if prices remain at or above incentive levels.

The energy transition paradox for miners

All this represents something of a paradox for miners. On the one hand is the sunlit uplands of a more metals-intensive world, at least during the first decade of the energy transition journey, where miners become growth stocks. On the other hand, miners are constrained in their ability to invest in growth to meet transition requirements by a lack of investor appetite to loosen the purse strings.

The challenge is multi-layered. Miners are all striving to deliver the best returns, while also tackling increasingly stringent ESG requirements and pushback from society against mine development, as opposed to material reuse. Then there is the whole debate about whether personal consumption and car ownership can continue in their current configurations. (I suspect that the model of unconstrained consumption will soon become archaic and regulated.) Plus, many major miners face shareholders’ desire to invest only in ‘unicorn’ projects (i.e. large, high-grade, long-life, low-cost, low-risk jurisdiction opportunities), of which few, if any, still exist.

Are miners locked into a boom-bust cycle?

As I have written previously, the miners’ paradox becomes even more extreme when considering the raw material requirements of a 2 °C pathway (our AET-2 scenario). With miners caught between a rock and a hard place, current investment trends and the fundamental outlook over the next five years suggest that the industry will underinvest in the required capacity.

As a result, we’ll most likely see a continuation of the classic boom-bust cycle as underinvestment begets shortages, which beget high prices, which beget overinvestment. In that scenario, miners, who should be the custodians of the energy transition, could instead end up inhibiting it.

The statement, sometimes credited to Albert Einstein, that “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result” feels pertinent here. It seems to me that unless we take action now, far from setting a course to deliver an accelerated energy transition, we will instead become locked into the insanity of mining boom and bust.

Get unique metals and mining insight in your inbox

This article is part of a series exploring opportunities and challenges in the world of metals and mining. Fill in the form at the top of the page to be alerted to new articles as they are published.