Coping with negative cash flow

Can the M&A market help oil companies bolster finances?

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Unlocking the potential of white hydrogen

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

The Edge

Are voters turning their backs on the EU’s 2030 climate objectives?

-

The Edge

Artificial intelligence and the future of energy

-

The Edge

A window opens for OPEC+ oil

-

The Edge

Why higher tariffs on Chinese EVs are a double-edged sword

It’s time to dust off the survival playbook. That trusty guide was no doubt consigned to the attic by management revelling in the success of recovery after the 2015 crisis. Suddenly those home truths – cutting costs, investment and shareholder returns – are needed again, and pronto. Our corporate analysis team calculates that overall spending needs to be cut by a hefty 41% year-on-year for companies to achieve cash neutrality at US$35/bbl Brent in 2020. It’s a tall order.

Selling assets to raise cash is another option in a time of financial crisis. I asked Greig Aitken, head of M&A analysis, how he sees the prospects for deals.

Will the sector look to sell assets?

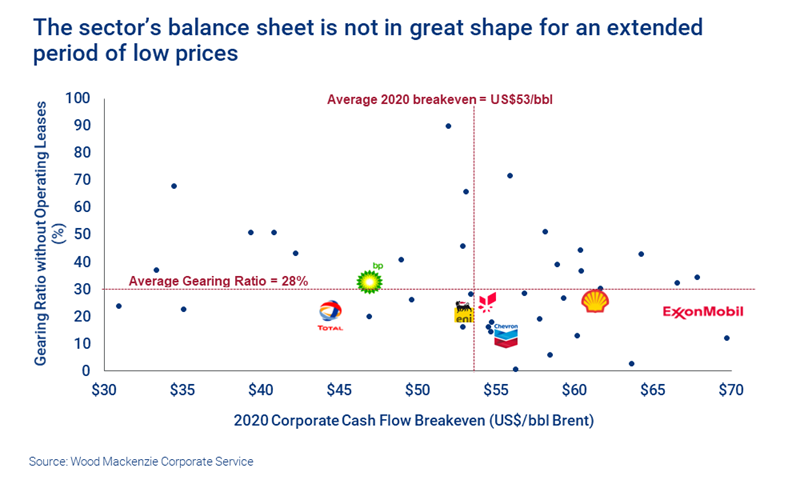

That’s for certain. The sector’s average gearing is already almost 30%, and likely to increase steeply in 2020 with negative cash flow and possible asset write downs at the end of the year. These dynamics will affect all companies, though gearing varies widely. Some companies will require urgent action to sell assets to bolster equity.

What are the chances of doing deals?

Not high – the M&A market is dead. Deal activity had been buoyant between 2016 and 2018, but it all started to go pear-shaped in 2019. The global deal count fell by 36% last year, and though spend rose, that was all down to Occidental’s acquisition of Anadarko. The underlying trend in 2019 was weak and that’s continued, with deal count in January and February 2020 among the lowest this century.

What are the challenges to get deals done?

Essentially, there are two main reasons for the low liquidity – lack of access to finance and huge uncertainty about future prices. Finance has dried up progressively over the last year with global equity markets effectively closed to the oil and gas sector for a host of reasons – modest returns and escalating ESG concerns among them. The current dislocation in financial markets compounds the problem.

A broad consensus on future oil and gas prices is also critical for buyers and sellers to make a market. The spread began to widen through 2019 and undermined activity. We’ve now entered a fresh hiatus where there’s no consensus at all. Sellers probably want a deal price based around US$60/bbl Brent. Buyers will be looking for assets on the cheap and trying to deal much nearer to the spot price – presently under US$30/bbl. All that points to zero chance of successful transactions in the immediate future.

How long before things might improve?

It depends primarily how price develops. If we look back to 2015/16, the period when Brent was down at US$45/bbl or below was fairly short-lived before prices recovered. M&A deal-making had a false dawn or two at that time but was largely in the doldrums for around 18 months.

What will determine a pick-up in activity this time is when the spread narrows. If, as some suspect, the oil price stays nearer to US$30/bbl for a prolonged period, it will take longer for the spread to close. In the near term, activity will be driven largely by financial stress, so the seller has to liquidate.

We’d expect a consensus to build gradually around a lower long-term planning price – nearer to US$50/bbl Brent than the US$60/bbl that’s prevailed over recent years.

What about the Majors’ divestment strategies?

Big Oil has actively churned assets in the last five years in a way it never had before. The sale of non-core assets raised capital to support share-buy backs, while strategically strengthening the core portfolio around advantaged assets. The Majors together have sold over US$65 billion of upstream assets in the last five years, and there’s more to do – between them targeting US$30 billion to US$40 billion of asset sales (not all upstream) in the next 24 months. With an average of US$4 billion of assets traded monthly in 2019, and that rate plunging in 2020, these targets look less and less realistic.

Equally, the sellers will be asking themselves if they really want to sell into a market where there’s no demand – and that’s without considering the practicalities of executing a transaction with the impediments caused by coronavirus.

Who are the potential buyers?

There are three groups, all at the better-capitalised end of the sector. First, Big Oil looking to bolster an already strong segment (tight oil, LNG, deepwater) or geographic positions. Second, US tight oil, where consolidation has to happen and the big may swallow up the small or financially stretched. Third, private equity, looking to buy at the bottom and freer than most from the ESG concerns that hound listed IOCs and NOCs.