Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

The Biden administration struggles to get a grip on fuel prices

Rising prices at the pump have become a political problem for President Biden, and nothing he is trying looks likely to be effective. Luckily for him, there is some relief on its way

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

The Big Beautiful Bill is close to passing

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

“Politician’s logic” was first identified in the great British sitcom Yes, Prime Minister: “Something must be done. This is something. Therefore, we must do it.” The Biden administration is showing signs of that kind of logic at work, as it struggles to get to grips with rising gasoline prices. The bad news is that none of its ideas looks likely to be very effective. The good news, for President Joe Biden and for US consumers, is that some relief is on the horizon anyway. The slump in crude prices this week, taking Brent down below $79 a barrel on Friday, is a harbinger of the better-supplied oil market that Wood Mackenzie analysts think is coming soon.

President Biden’s approval rating has been slumping since the summer, and rising gasoline prices seem to be one of the reasons. The average retail price of regular gasoline this month has been about $3.40 a gallon, its highest for more than seven years. In California, which has an idiosyncratic fuels market because it demands higher specifications for its gasoline, prices have hit all-time highs.

In real terms, adjusted for inflation, US gasoline prices are still lower than they were for most of the late 2000s and early 2010s. But by the standards of the past seven years, they are uncomfortably high. In the UK and some other countries, people on the lowest incomes are shielded from the impact of higher fuel prices because they often do not own cars. In the US, it is the poorest people who face the greatest burden from rising gasoline prices, as measured by the percentage of the household budget spent on fuel. Gasoline and fuel oil were the fastest-rising items in the Consumer Price Index in the year to October, up about 50% and about 59% respectively over 12 months. They are significant contributors to the overall rise in CPI inflation.

Jennifer Granholm, the energy secretary, has been making the point that in the long term, the solution to exposure to oil price volatility is to shift away from gasoline and diesel towards electric vehicles. But the administration’s goals for 2030 and beyond are not much help when people have bills to pay this week, and there are elections for Congress next year and for the presidency in 2024. It was a sign of the urgency of the issue that when President Biden met President Xi Jinping of China for a three and a half hour teleconference on Monday, the official readout from the White House noted that they had discussed “the importance of taking measures to address global energy supplies”. (China has been facing its own energy supply crisis over coal and gas this year.)

For months, the administration’s main tactic has been to urge the OPEC+ countries to accelerate the unwinding of the production cuts they agreed as the pandemic hit in April 2020. So far, those efforts have been in vain: the group has stuck to a steady increase in its official production limit of 400,000 barrels per day each month, following the plan that ministers agreed in July. Suhail al-Mazrouei, the energy minister of the United Arab Emirates, commented this week that growth in supply “should be enough”. He added: “We need not panic. We need to be calm.”

This week, the administration’s effort stepped up a gear, and its focus shifted. On Wednesday President Biden wrote to Lina Khan, chair of the Federal Trade Commission, asking it to investigate possible “illegal conduct” affecting gasoline prices. His letter follows an earlier call from White House for the FTC to investigate. Back in August Brian Deese, director of the National Economic Council, wrote to Khan saying: “While many factors can affect gas prices, the president wants to ensure that consumers are not paying more for gas because of anti-competitive or other illegal practices.” Khan responded that the FTC would be applying more rigorous scrutiny to oil and gas M&A activity, especially in the fuel retailing industry.

The competitiveness of the US fuels market has been studied many times over the decades. An FTC investigation in 1973 concluded that it had "reason to believe" that eight large oil companies were violating the Federal Trade Commission Act (Act), which covers “any unfair method of competition or unfair or deceptive act or practice in or affecting commerce”, and started a legal battle that went on for the rest of the decade.

In 2011, the FTC reported that “review and oversight of the oil and natural gas industries will remain a centerpiece of our work for years to come.” But a detailed study by the commission that year concluded that the key feature of the market was that “crude oil prices continue to be the main driver of gasoline prices.” That study noted that fuel prices appear to react faster when crude is rising than when it is falling. “Prices are said to go up like a rocket but fall like a feather”. However, the long-term impact of that on consumers is unclear.

On this occasion, the evidence cited by the president seems flimsy. He notes in his letter to the FTC that in the past month the wholesale price of unfinished gasoline has fallen by 5%, while average prices at the pump have risen by 3%. If anyone wants to prove there is a fundamental problem of inadequate competition in the retail fuels market, they will need more than a month of data.

Alan Gelder, Wood Mackenzie's vice-president of refining, chemicals and oil markets, noted that the US oil majors own less than 5% of the US retail fuel stations, so they have limited pricing power. The biggest fuel retailer in the US is 7-Eleven, and even that has fewer than 9,000 sites, out of a national total of about 150,000 sites. The sector is highly fragmented.

Meanwhile, there has been growing speculation that the administration will announce a release of more crude from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Reuters reported this week that the US has been asking other large oil-consuming countries, including China, Japan and India, to join in a co-ordinated release of reserves. Oil is already being released from the US SPR under a sale programme announced in August, but co-ordinated intervention in the market is unusual, and might have an impact on market psychology. The experience of past releases has shown that they can move prices for a while, although the impact is typically transient.

Another action by the administration this week to address oil supply has been on the agenda for years, and will not show any results in terms of increased production for more years to come. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management held a lease sale for acreage in the Gulf of Mexico, generating about $192 million in high bids for 308 tracts covering 1.7 million acres in federal waters. The sale, which was held about eight months later than originally planned, attracted bids from 33 companies. That compares to 27 companies participating in the last pre-pandemic lease sale, in August 2019, so it looks like a positive indicator in terms of future investment. And it sent a signal that, despite its commitment to cutting US greenhouse gas emissions, the Biden administration is not attempting to block all new oil and gas development. But it does nothing to help the president’s immediate problem.

Even taking all of these moves together, the consequences for gasoline prices are likely to be minimal. It is hard to see anything the administration is doing now having a noticeable impact on oil markets by the time of the midterm elections next year. Luckily for President Biden, however, the tightness in world oil markets that has driven crude and hence gasoline prices higher is set to ease next year. The steady pace of production growth from the OPEC+ countries may be frustrating for President Biden, but it is steadily bringing more crude on to the market. And at the same time, output from several non-OPEC countries is picking up. “Individually they may be fairly small increases, but they all add up,” says Ann-Louise Hittle, head of Wood Mackenzie’s Macro Oils service.

She forecasts that non-OPEC production in the first quarter of 2022 will be 650,000 b/d higher than in the fourth quarter of 2021, with countries including Russia, Norway, the UA, Brazil, and Canada all reporting increases. Even though oil demand is continuing to grow, inventories are likely to increase in the first quarter of next year. That may not bring President Biden all the relief on gasoline prices that he would like. But it does at least look likely to have a greater impact on the market than any of the ideas the administration is currently trying.

In brief

European gas and power prices have been surging again, after easing off slightly in October. Wood Mackenzie analysts said they expected market tightness to last until the second half of 2023.

Jeremy Weir, chief executive of Trafigura, warned there was a risk of rolling power outages in Europe this winter. “We haven’t got enough gas at the moment quite frankly, we’re not storing for the winter period,” he said. “So hence there’s a real concern that there’s a potential if we have a cold winter that we could have rolling blackouts in Europe.”

Royal Dutch Shell plans to lose the “Royal Dutch” from its name and relocate its global headquarters and tax residence from the Netherlands to the UK. It will also simplify its share structure.

Saudi Arabia is planning to issue its first green bond. Sustainable investors are debating what to make of it, Bloomberg reported.

Net Power, a company with an innovative technique for burning natural gas for power generation that produces a stream of carbon dioxide suitable for storage or use, has delivered its first electricity to the grid in Texas. The company’s chief executive said: “This is a Wright-brothers-first-flight kind of breakthrough for energy: zero-emission, low-cost electricity delivered to the grid from natural gas-fueled technology.”

The US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has delivered its final report on the blackouts that hit Texas during Winter Storm Uri in February of this year. It concluded that the power industry needed to make its operations more resilient in cold weather, highlighting “the critical need for stronger mandatory electric reliability standards, particularly with respect to generator cold weather-critical components and systems”. Most of the generating units that experienced unplanned outages in the cold were gas-fired plants (58%), followed by wind (27%), coal (6%), solar (2%), with four nuclear units making up less than 1%.

And finally, a popular new entertainment: watching people clean solar panels. One of the more innocuous enthusiasms of the internet is for videos showing industrial processes or craft skills, which satisfy the impulse to see tasks performed accurately and neatly. The process of cleaning solar panels, as shown in this short clip, has recently been picked up for these “oddly satisfying” videos that are popular on Reddit and Instagram, and there is indeed something strangely pleasing about watching the shining glass surface emerge from under a thick coating of sand. Keeping panels clean can, of course, be crucial for optimising their performance, especially in dry and dusty locations. As solar power spreads around the world, providing cleaning services looks like a good business opportunity. But as this recent Twitter thread warns, it can be a frustrating exercise without the right equipment.

Other views

Gavin Thompson — How green hydrogen can ensure Australia’s place in the sun

Andrew Brown — The plastics industry must go under the knife for a more sustainable future

Julian Kettle — Is the end of coal in sight?

Russell Gold — In praise of… Enron?

COP26 opinion roundup

Wood Mackenzie analysts — Why COP26 was a success, albeit a qualified one

Adam Tooze — The Cop26 message? We are trusting big business, not states, to fix the climate crisis

Christiana Figueres — Cop26 took us one step closer to combating the climate crisis

John Sutter — Why Cop26 leaves me furious, and searching for hope

Xavier Vives — Was Cop26 cheap talk?

Walter Russell Mead — The Cop26 summit and the global age of shams

Quote of the week

“As scary as [the police] might be, as scary as taking action which might ostracise you from certain communities might be, it’s not as scary as the future we are heading to.” — An Australian climate activist, identified only as Hannah, explained her reasons for shutting down coal exports from the Port of Newcastle on Wednesday by climbing machinery and pressing an emergency stop button. A group called Blockade Australia has been mounting a series of actions to disrupt coal shipments from the port. The New South Wales Police Commissioner has warned that activists from the group who have been interfering with train movements could face up to 25 years in prison.

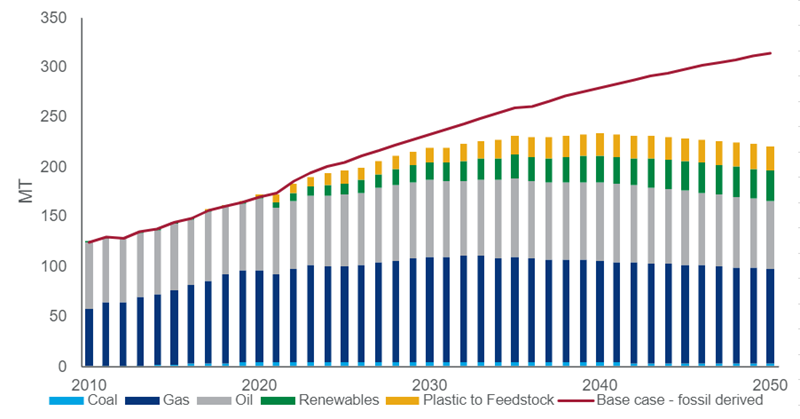

Chart of the week

This comes from our latest Horizons report, titled ‘Plastic surgery – reshaping the profile of the plastics industry’. It examines the implications of growing concerns about the environmental impact of the production and use of plastics, concluding: “The outlook for an industry that maintains the current growth model is not attractive… [But] a more appealing future is there for the taking.” The chart shows feedstock demand for plastic production in two possible worlds. The line represents Wood Mackenzie’s base case forecast, with demand for plastics growing by about 90% by 2050. The bars show an alternative scenario for “peak plastic”, a vision of a more sustainable future with restricted use of disposable plastics, and diversified inputs including bio-feedstocks and recycled material. One particularly striking point is that demand for oil and gas as feedstocks, which in the base case forecast keeps growing steadily to 2050 and beyond, in the “peak plastic” scenario levels off in the early 2030s and begins to decline.