Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Delaying deepwater decommissioning

Can operators keep wells running for longer?

3 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin oversees our Europe, Middle East and Africa research.

View Gavin Thompson's full profileLuiz Hayum

Upstream Research Principal Analyst, Latin America

Luiz Hayum

Upstream Research Principal Analyst, Latin America

Luiz's expertise lies in valuing upstream assets in Latin America.

Latest articles by Luiz

-

The Edge

Delaying deepwater decommissioning

-

Opinion

Deepwater decommissioning: three key things to know

-

Opinion

Latin America upstream: opportunities and challenges

-

Opinion

Can Brazil’s mature pre-salt oil fields continue stellar performances?

-

Opinion

Deepwater's Latin America comeback

Amanda Bandeira

Research Analyst, Latin America Upstream

Amanda Bandeira

Research Analyst, Latin America Upstream

Amanda is an expert in valuing individual upstream onshore and offshore assets in the Latin America region.

Latest articles by Amanda

-

The Edge

Delaying deepwater decommissioning

-

Opinion

Deepwater decommissioning: three key things to know

-

Opinion

Petrobras kicks off Marlim revitalisation project in Brazil

Deepwater drilling supercharged the global conventional upstream industry this century, unlocking lucrative resources previously out of reach. From its first production in the late 1990s, deepwater projects will deliver over 11 mmboe/d in 2024.

Nothing gold can stay. Significant decommissioning bills loom large as production facilities on the sector’s pioneering early fields near the end of their operating lives.

With oil demand set to remain strong and the outlook for prices more positive, what options do operators have to keep wells running for longer? Gavin Thompson, Vice Chair EMEA, spoke to Luiz Hayum and Amanda Bandeira from our Upstream and Carbon Management research team to find out.

Where are the decommissioning hotspots?

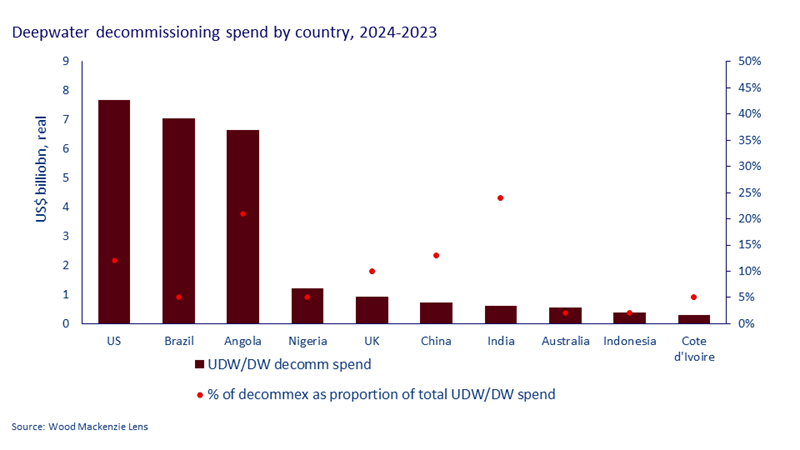

Deepwater decommissioning requires deep pockets. Among the highest-cost upstream abandonment plays, leading deepwater countries and operators face up to US$27 billion of decommissioning expenditure (decommex) in the next 10 years.

Across mature deepwater projects globally, Brazil, the US Gulf of Mexico and Angola are the standouts. Together, these three deepwater plays make up 80% of forecast decommex over the next decade. Angola faces a particularly hefty bill as a proportion of total deepwater spend, following an extended period of slow investment in new field development.

Why is deepwater decommex so expensive?

Decommissioning any offshore project requires significant spend, but deepwater brings further challenges compared to shallow-water facilities. Deepwater projects have high operating costs even after production ends, and decommissioning requires cutting-edge equipment to access wells, lift subsea equipment and safely remove enormous floating platforms for dismantling or re-use.

With up to five production facilities set to be removed each year over the next decade, a growing number of wells will need to be plugged and abandoned. A tight deepwater rig market is also ratcheting up decommissioning costs. With rates having doubled over the last five years, operators are increasingly looking to specialised intervention vessels as an alternative to rigs.

Who pays decommex?

The most effective way is for all companies to pay their share of future decommex into a fund over the life of the project, as required by Angola and Nigeria. This ensures any change of ownership means the new owners will inherit a share of the decommex fund built up by the seller.

Ideally, payments into a fund should be treated as recoverable costs (within PSCs) or as tax deductions to ensure the government pays its fair share. Many modern PSCs now include decommex fund obligations, but many earlier ones do not. Tax-deductible decommex fund commitments are much less common in concession systems, including in the US.

Can companies kick decommex down the road?

It’s a given that most operators will do all they can to defer spend on decommissioning.

Substantial value can be created by postponing plug-and-abandonment operations and generating continued value from mature fields where possible through incremental developments, infrastructure sharing and facility upgrades.

Maximising available infrastructure is key. We estimate that 80% of deepwater fields either in production or approved for development have undeveloped prospects within 30 kilometres. This creates excellent opportunities for tiebacks to existing infrastructure to extend productive life. WoodMac analysis shows most deepwater fiscal regimes support positive economic results for typical tie-back developments. A 50-million-barrel oil tieback delivers an average 22% IRR for the top 10 deepwater countries ranked by decommissioning liability.

Much depends on the scale and cost of undeveloped resources. For some fields, maintaining production can defer end-of-life costs but dilute advantage when compared to delaying permanent decommissioning for as long as regulation allows. There is also a trade-off between the value of extending production from older wells and increasing emissions intensity by doing so.

Deepwater plays are also rising up the ranks of potential carbon capture and storage plays, offering opportunities to extract new revenue. Infrastructure is again key. Most early deepwater fields targeted oil, with production delivered via offshore loading facilities, limiting the opportunities to reverse pipeline flows to transport CO2 for storage.

Could decommex deter future investment in deepwater?

Absolutely not. As the leading players double-down on advantaged barrels – low-cost, low carbon-intensive supply – deepwater is the gift that keeps on giving. Most of the giant discoveries of the last decade, including Brazil, Guyana, Suriname and Namibia, have all been in the deepwater.

And with decommex less than 10% of the 10-year forecast deepwater capex for seven of the ten top companies operating in the deepwater space, deepwater’s share of upstream investment is set to double by the middle of the decade compared with 2020.

Make sure you get The Edge

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers curates unique insight into the hottest topics in the energy and natural resources world.