Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Renewable energy shows its strength in the coronavirus crisis

Earnings announcements from oil majors and utility groups this week have demonstrated the superior resilience of electricity businesses

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

Editor's note: This article is part of our ongoing analysis of the impact of coronavirus and the oil price crash. Visit our coronavirus and oil market in crisis hubs for more.

If you step out into the streets of a major city in America, Europe or India right now, one thing is likely to strike you immediately: how clear the air is. Business closures and restrictions on movement to curb the spread of Covid-19 have meant that fuel consumption has slumped, bringing dramatic improvements in local air pollution.

Greenhouse gas emissions have also fallen sharply. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast on Thursday that world’s energy-related carbon dioxide emissions would be down almost 8% in 2020 as a whole, a reduction six times larger than the previous record drop in 2009. In the US, those emissions are likely to drop by 7.5% this year, according to the government’s Energy Information Administration.

The declines have raised hopes among some optimistic observers that the Covid-19 pandemic could help achieve lasting reductions in emissions, but it is easily possible to argue the opposite point. The fact that it has taken lockdowns affecting billions of people to deliver a cut in carbon emissions that is still well short of what is needed to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement shows how dependent on hydrocarbons we still are, and how difficult it will be to change that.

In a review of the impact of the coronavirus published on Thursday, the IEA pointed out that in absolute terms the fall in global energy consumption this year is unprecedented.

But while the short-term drop in emissions will be reversed in line with the recovery in economic activity, there have been some signs this week that the pandemic could accelerate the long-term transition towards lower-carbon energy.

As Wood Mackenzie experts discussed in a recent webinar, some new energy businesses are suffering in the downturn. Consumer-facing industries including electric vehicles and residential solar are seeing sharp declines. Slower growth in demand for power in and restricted access to credit in emerging economies could put a brake on investment in renewables. Renewable energy technologies that compete against hydrocarbons are under pressure from bargain basement oil and gas prices. Supply chain disruptions and restrictions on construction work are slowing investment in wind power.

Despite all that, though, renewable energy has been holding up reasonably well, and certainly better than oil. Well over half the world’s oil consumption is used in transport, which has been one of the sectors hit hardest in the downturn. Electricity demand has also fallen — in the US it was down about 6% in April compared to the same month of 2019 — but it has not collapsed the way the oil market has. Prices have also held up much better for electricity than for oil. That contrast was sharply demonstrated this week by the first quarter earnings from some of the oil majors and some leading power companies.

Shell cuts its dividend but holds on to its emissions ambitions

On Thursday Royal Dutch Shell announced that it was cutting its quarterly dividend for the first time since World War II: a 66% reduction to 16 cents. Ben van Beurden, chief executive, said the cut was intended to bolster resilience and strengthen Shell’s balance sheet, “given the continued deterioration in the macroeconomic outlook and the significant mid and long-term uncertainty”.

The move was announced as Shell reported a 46% drop in earnings for the first quarter and warned that the second quarter would be worse, as it faced “unprecedented and intense economic headwinds”. It is cutting annual operating costs by $3-4 billion from 2019 levels, and has lowered its capital spending budget for 2020 to less than $20 billion, down from a previously planned $25 billion.

The dividend cut did not exactly come out of the blue. Simon Flowers, Wood Mackenzie’s chief analyst, argued more than a month ago that there was “a strong argument” for the oil majors to cut their payouts. There was still a negative response from investors, however: Shell’s shares fell by over 11% on Thursday.

But even as the company is taking these radical steps to strengthen its financial position, it is pledging to stay the course on cutting emissions. Van Beurden told analysts in a presentation that Shell was “protecting some of our spend across all of our businesses, including power, to continue to provide lower-carbon energy products and solutions today while building profitable lower-carbon energy business models for the future.”

Luke Parker, a Wood Mackenzie vice-president of corporate analysis, said a permanent dividend reset from Shell would help build those businesses, funding “an accelerated strategic pivot to 'Big Energy’.” More cash flow from Shell’s oil and gas cash operations will be available to be invested in renewables, EV infrastructure, and other low-carbon technologies.

Other oil majors are under similar pressure to cut distributions to shareholders. BP kept its first quarter dividend unchanged when it reported its earnings on Tuesday, but its payout is under review, and there is a strong likelihood that it will follow Shell’s lead and cut.

Like Shell, though, BP is sticking to its ambitions for cutting emissions and investing in low-carbon energy. Bernard Looney, chief executive, said that in this “very brutal environment”, he was even more committed to the aim of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, in part because of the superior resilience of renewable energy. BP is sticking with its plan to invest about $500 million in low-carbon energy this year, although it has cut its total planned capital spending by 25% to $12 billion.

Renewables companies thrive in the downturn

The resilience of renewable energy in the coronavirus crisis was demonstrated impressively this week by Ørsted, the power company formerly known as Danish Oil & Natural Gas. It sold the last of its upstream oil and gas assets in 2017, and its loss-making LNG business late last year. Renewable sources now provide 90% of the power and heat that it produces.

On Wednesday Ørsted reported a 27% increase in profits from continuing operations in the first quarter, and confirmed it was still on course for a drop of only about 6% in its earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation for the year as a whole. It said in a statement: “We have no indication that the Covid-19 situation will significantly impact our full year earnings.” There are many other companies that wish they could say the same.

Iberdrola, the Spanish utility group that is active in renewable energy, also this week reported a 5% rise in first quarter adjusted net profit. The company’s presentation for investors highlighted the possibility that climate-focused stimulus plans such as the European Green Deal could help its business. It is aiming to hire 5,000 people and step up capital spending by 12% to EUR10 billion this year.

There were other indications of the continuing health of renewable energy in some announcements on new projects. The Abu Dhabi Power Corporation told Greentech Media that a consortium including EDF and Jinko Solar had submitted the winning bid for a 2 gigawatt solar project to come into service in 2022, which will be the largest in the world on a single site.

The price of the power from the site is also a record breaker, according to Abu Dhabi Power. At US$13.50 per megawatt hour, it is the lowest yet reported for a solar project, the company said.

In the US, meanwhile, the number of large (meaning 100 megawatt or more) solar projects is rising fast.

Investor interest in power and renewable energy remains high, as can be seen from the close last month of BlackRock’s Global Energy and Power Infrastructure Fund III. It raised $5.1 billion, well above its original target of $3.5 billion.

Oil oversupply may have passed its peak, but the recovery is slow

Although world energy use remains well below normal, there have been some faint signs of revival this week. The peak in global oversupply of oil may have passed, with production cuts from the OPEC+ countries starting to take effect on May 1, production shut-ins increasing in the US, and demand flickering slightly higher.

In China, highway traffic is back to normal, and the number of flights is ramping up.

Around the world there were on average about 74,000 flights a day in the past week, according to Flightradar24. That is down from about 178,000 a day in February, but up from 64,000 a day in mid-April.

Road transport is picking up a little in the US and some other countries. In New York, a week or two ago you could just step out on into the street and be confident you would be safe. Now you have to look. On Tuesday traffic congestion was 13% at the evening peak in New York, according to TomTom data, down from an average of 66% in 2019, but up from 7% last week.

US gasoline demand was 5.86 million barrels a day in the week to April 24, up 10% from the previous week although still down 36% from a year ago, according to the EIA.

Across the US, restrictions on businesses and movement mainly remain in effect, and in the places where they are being lifted, the response from the public has been very cautious. The governor of the state of Georgia has allowed businesses including gyms, hair salons, tattoo parlors and bowling alleys to reopen, but many have remained closed. The ones that are open are expected to maintain social distancing and operate at less than full capacity.

The Fed moves to help US oil producers

Benchmark WTI crude ending the week at about $20 a barrel, after a volatile week in which it was only a little above $10 at one point, keeping the pressure on the Trump administration to provide financial support for the industry.

The idea of a special oil-focused bailout plan has been controversial, however. The American Petroleum Institute has opposed it, and was particularly critical of the suggestion that the federal government might take equity stakes in oil companies. Its president Mike Sommers told Axios: “Once you invite the government into these businesses, there are long-term repercussions for that, and I think that has weighed heavily on this industry's mind.” On Thursday the energy department ruled out that idea.

One small step the administration has taken is to allow private companies to use space in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve sites, to relieve some of the pressure on oil storage in North America.

The potentially more significant move came from the US Federal Reserve, which on Thursday said it would expand the scope of its Main Street Lending Facility for companies in financial difficulties. The new rules apply to all companies, but have the effect of making more oil companies eligible. Companies with 15,000 employees and $5 billion in revenues can now receive loans from the facility, up from the previous limits of 10,000 workers and $2 billion. Eligibility has been also expanded for companies recently downgraded to junk credit ratings.

Dan Brouillette, energy secretary, described the move as “great news out of the Fed today in support of struggling US energy companies”. Bonds in some companies including Occidental Petroleum and Antero Resources rose after the Fed’s announcement. However, Brouillette suggested he still wanted to do more, saying he was still working with Treasury secretary Stephen Mnuchin “to provide other relief”.

Production cuts agreed in Norway, debated in Texas

Norway is making its contribution to relieve global oversupply: it is joining in concerted international output reductions for the first time in 18 years. The government is ordering companies to cut production by 250,000 barrels per day, or 13%, in June, and by 134,000 b/d from July to the end of the year. It is also delaying the start-up of new fields, with the effect that total production is expected to be 300,000 b/d lower by December.

Similar action to curb some US production is still being considered by the Texas Railroad Commission, which has long-dormant legal powers to control the state’s output. However this week Wayne Christian, the regulator’s chairman, spoke out against the idea, saying he would “vote against curtailing Texas oil production and stick to free market principles”.

With Ryan Sitton, one of the other two commissioners, having backed the idea in the past, that could leave Christi Craddick as the swing voter when the question comes up for a decision on May 5.

And finally…

Controversy continues to rumble around Planet of the Humans, the documentary about renewable energy backed by firebrand filmmaker Michael Moore. In an interview with The Hill, Moore talked about his “huge admiration for all of our fellow environmentalists”, but the feeling does not appear to be reciprocated. Climate scientist Michael Mann described the film as full of “various distortions, half-truths and lies”. The most detailed criticisms came in a scathing review from Leah Stokes of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Oil closes in on peak oversupply

Gavin Thompson — For Asia’s NOCs, it’s time to go big or stay home

Will Nichols and Olivia Dobson — Seven challenges Covid-19 raises for the climate agenda

Trent Jacobs — The great shale shut-in: Uncharted territory for technical experts

Liam Denning — What fracker earnings really need are fewer frackers

Clyde Russell — Seaborne thermal coal prices slide as India takes coronavirus hit

Julia Pyper — India’s clean energy revolution is on pause during the coronavirus crisis

Quote of the week

“We’re choosing to store our oil down in the reservoir. We’re choosing not to produce it. We’ve voluntarily curtailed for the month of June 460,000 barrels a day, which represents about a third of our company’s production.” — Ryan Lance, chief executive of ConocoPhillips, explained the company’s response to the critical shortage of oil storage capacity in the US.

Chart of the week

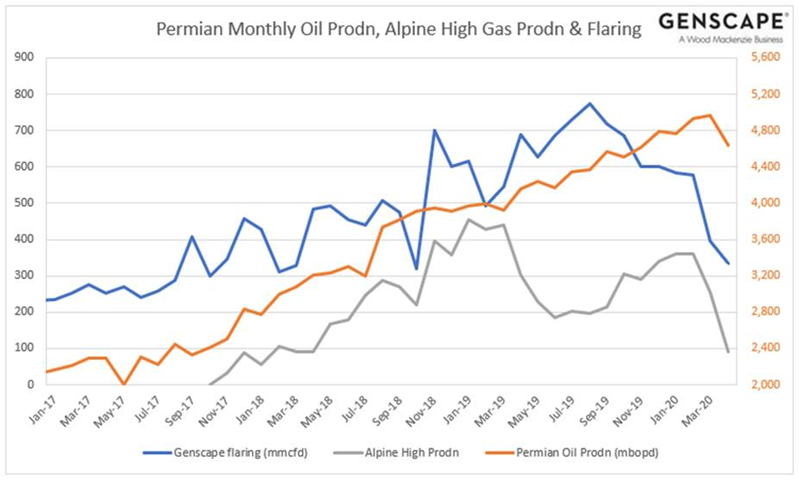

As oil production boomed in the Permian Basin over the past decade, so did the volume of associated gas being burned off in flares. The slowdown in activity this year has meant that flaring has fallen dramatically. This chart, compiled by Randall Collum of Wood Mackenzie’s Genscape service, is based on satellite radiant heat data used to calculate flared volumes. You can see how flaring — the blue line — hit a peak at the end of last summer and has since been on a declining trend. Initially, the crucial factor seems to have been the full startup of the Gulf Coast Express pipeline, which takes gas out of the Permian to the coast. This year, falling output has been driving the reduction. As operators have cut production, first from the Alpine High formation in west Texas and then from the Permian as a whole, they have less need to flare off gas.

Genscape: the source of truth and insight for global energy markets

Genscape, a Wood Mackenzie business, operates the world’s largest private network of in-field monitors and distribute industry-leading alternative data, delivering unsurpassed market intelligence across the commodity and energy spectrum including power, oil, natural gas, natural gas liquids, agriculture, biofuels, and maritime freight.

Wood Mackenzie acquired Genscape in August 2019