Interested in learning more about our gas & LNG solutions?

US gas exporters target a changing European market

Europe is replacing its lost imports from Russia with LNG. The shift is putting its gas infrastructure under strain

13 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

-

Opinion

What the conflict between Israel and Iran means for energy

There was a time when US natural gas companies did not really need to know very much about overseas markets. Up until 2016, there were pipeline connections to Canada and Mexico, but no LNG exports from the Lower 48 states. North America was effectively an island for gas, and its markets had their own dynamics. Producers could afford to see European and Asian markets as far-away countries of which they knew nothing.

In the mid-2000s, if US natural gas companies thought about the global LNG market, it would generally have been to consider potential suppliers. North America’s gas imports were expected to grow rapidly.

The shale gas revolution, however, has transformed that picture. Now the US is becoming increasingly integrated into global gas markets as one of the world’s largest exporters. US LNG exports are running at a little over 11 billion cubic feet per day, which is about 11% of the country’s marketed natural gas production.

One consequence of that is that North American prices are starting to be influenced by global trends in LNG markets. Another is that US producers are starting to be able to sell at international prices. EOG Resources, for example, signed a deal in 2019 for gas to be exported from Cheniere Energy’s Corpus Christi plant.

The contract was expanded and extended in February of this year, adding additional volumes, with the result that when sales reach their peak levels, about 65% of the gas will be sold at prices linked to the JKM benchmark for LNG in Asia. The rest will be sold at prices linked to the US benchmark Henry Hub. Apache, Tourmaline and ARC have also signed contracts for sales linked to JKM and other international prices.

The appeal of such contracts now is obvious. JKM futures for this winter peaked at over $80 per million British Thermal Units in August, when the equivalent Henry Hub contracts were just over $10 / mmBTU. November 2022 futures for European benchmark TTF gas have dropped about 65% from their August peak, but were still trading this week at the equivalent of about $35 / mmBTU, while Henry Hub was at about $5.30 / mmBTU.

More US producers are keen to take advantage of these much higher global prices, which seem likely to persist for several years, if the tensions between Russia and the EU over Ukraine continue. A Chesapeake Energy executive indicated at a recent Hart Energy conference in Houston that the company was looking at selling 20-25% of its production at international prices. Other US producers are also looking into the opportunities in markets around the world.

However, recent developments in Europe have underlined that exploring new territories can create new challenges. TTF, settled in the Netherlands, is seen as the European benchmark, but prices in the UK, Spain, Italy and France can be very different. Limited pipeline capacity to move gas around Europe means that local market conditions can vary widely. November 2022 futures for UK benchmark NBP gas were trading at about $23 / mmBTU on Thursday, about 35% below the equivalent contract for TTF.

A glaring sign of the disparities between different European gas markets came this week from Spain, which has about a third of all Europe’s LNG regasification capacity. Enagas, the operator of Spain’s gas transmission system, warned that a mismatch between supply and demand for LNG coming into the country had resulted in “sustained episodes of very high levels of stocks in the tanks of all the regasification plants” in its gas network.

The strain on tank capacity is expected to continue at least until the first week of November. Enagas declared an “exceptional operating situation”, meaning that it would postpone any deliveries of LNG for which capacity had not already been booked, or which might result in storage tanks being overfilled. “Any request for flexibility that implies an increase in the amount of LNG to be unloaded… will be denied,” it said. There are 35 loaded LNG tankers currently parked off the coast of Spain, waiting to find a slot to unload.

Those market conditions have put down pressure on prices. Gas for day-ahead delivery on Spain’s PVB hub has been trading at only about $13 / mmBTU.

This week, there has been a breakthrough for attempts to build additional gas pipeline capacity to help relieve this kind of bottleneck. Completion of the proposed Midi-Catalonia (MidCat) pipeline route across the Pyrenees was held up by international wrangling: Spain has been keen to push ahead with the project, while France opposed it. On Thursday, the heads of government of France, Spain and Portugal announced an agreement to go ahead with an alternative project: the undersea BarMar pipeline from Barcelona to Marseille. But it will take time for that capacity to available: the projection is that BarMar will be operational by the end of the 2020s.

Stepping back from individual projects to look at the big picture of European gas flows, we can see a shift under way that is as great as the transformation of North American markets as a result of the shale boom. The traditional orientation of US gas infrastructure was configured to deliver molecules from the Gulf of Mexico region and the Rockies, where they were produced, to the centres of demand in the north and east. The emergence of the Appalachian Basin as the largest gas-producing region in the US has turned that model on its head, as gas started to flow west and south. Gas takeaway capacity out of the northeastern US increased from less than 5 bcf/d in 2008 to almost 25 bcf/d in 2020.

In a similar way, European gas infrastructure has since the 1970s set up to move gas from east to west, from Russia’s gasfields to demand centres in Germany and beyond. Now Europe’s gas imports from Russia have plummeted and LNG, mostly brought in to regasification plants in western Europe, is filling the gap. There is a growing need for capacity to move gas from west to east, and EU governments’ goals of ending their reliance on Russian gas completely suggest that the shift will be permanent. Gas pipeline infrastructure will need to be reconfigured as radically as it was in the US, and new LNG regasification capacity will have to be added.

Emissions reduction goals have been seen by many European politicians as reasons not to invest in natural gas infrastructure, but the urgency of the current crisis is pushing aside some of those objections. Some infrastructure can be future-proofed for the transition to lower-carbon energy: the BarMar pipeline, for example, is intended ultimately to move green hydrogen, even though it is most likely initial to transport natural gas.

New regasification facilities in the markets with the greatest need will also help ease bottlenecks. Germany plans to have five Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs) operational by the winter of 2023-24. France has approved TotalEnergies’ plan to have the Cape Ann FSRU in service at Le Havre by September next year.

Even though all this investment is now under way, reshaping gas flows around Europe remains a massive task that will not be completed in a year or two. And for as long as the process is under way, local market conditions will remain important, and pricing across Europe will continue to be complex.

“Until last year, price differentials between different European hubs would typically not be more than 10 or 20 cents per mmBTU,” says Kristy Kramer, who leads Wood Mackenzie’s gas market research team. “We’re not going back to that again any time soon.”

President Biden seeks to put a floor under oil prices

When the White House announced that President Joe Biden would be making a statement about fuel prices on Wednesday, there was a fresh flurry of speculation that he could be about to announce some kind of ban on exports of crude oil or refined products. The midterm elections on November 8 are approaching fast, and the Democrats are trailing in the polls, with voters indicating that rising gasoline prices are more likely to make them vote Republican.

The administration has refused to rule out an export ban, despite the likelihood that it would create havoc in world markets and cause significant damage to the US industry. Wood Mackenzie analysts said a ban on exports of refined products would be like “a high-risk game of musical chairs”.

As it turned out, the president’s intervention was more measured than that. His strategy, as set out in Wednesday’s statement, has two tracks. For the near term, the administration is continuing to release crude from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The Department of Energy awarded a further 10.15 million barrels, bringing the total so far to about 165 million barrels. That leaves a further 15 million barrels to go from the 180 million barrel release announced in March, and we expect those to be awarded before the end of the year.

The longer-term plan was more interesting, and provided some answers to the question of what administration plans to do about refilling the SPR. President Biden said the US government would start buying oil again when crude prices drop to $70 a barrel, with the aim of giving producers greater certainty about their revenues. “Oil companies can invest to ramp up production now, with confidence they’ll be able to sell their oil to us at that price in the future: $70,” the president said. It was in effect a promise of a price floor for oil.

At a time when front-month West Texas Intermediate Futures are trading at around $85 per barrel, and the OPEC+ group is moving to tighten supply, a price floor of $70 a barrel might not seem particularly significant. WTI futures for December 2024 were already trading at around $70 a barrel before the president’s announcement.

However, it is less than three years since WTI futures prices were briefly negative. Given the volatility of crude markets, a pledge from the government to support prices at $70 could easily become relevant. Particularly as the world economy may be heading into a period of turbulence.

The announcement also has some symbolic importance. In his statement, President Biden made a point of rejecting accusations that his administration had worked to suppress US oil production growth, a perception that is widely held in the industry. “My administration has not stopped or slowed US oil production; quite the opposite,” he said. “By the end of this year, we will be producing 1 million barrels a day, more than the day in which I took office. In fact, we’re on track for record oil production in 2023.”

Even if the $70 a barrel price floor is never tested, it is still a sign of how President Biden’s rhetoric on oil has shifted since the early days of his administration, when his energy strategy was focused almost entirely on climate change.

In brief

A vote in the UK Parliament on whether to lift the ban on hydraulic fracturing imposed in 2019 led to chaotic scenes in the House of Commons. The following day, the prime minister Liz Truss resigned. The government won the vote comfortably, by 326 votes to 230, but 40 Conservative MPs did not vote to support it. Chris Skidmore, a Conservative MP and former minister, tweeted: “As the former Energy Minister who signed Net Zero into law, for the sake of our environment and climate, I cannot personally vote tonight to support fracking and undermine the pledges I made at the 2019 General Election. I am prepared to face the consequences of my decision.”

Hydraulic fracturing in the UK is a fiercely controversial political issue because of widespread local opposition to the impacts of oil and gas production. Its significance for the industry, however, is more limited. Wood Mackenzie analysts say it will be very challenging to establish an unconventional oil and gas production industry in the UK. They wrote last month: “We believe [UK] shale gas faces too many political, technical, economic and funding headwinds to make a material impact this decade.”

Josep Borrell, the EU’s High Representative for foreign affairs and security policy, gave an important speech talking about the future of Europe. The EU’s prosperity, he said, had been based on two factors that could not be relied on in the future: access to China for both imports and exports, and cheap energy coming from Russia. Russian gas had supposedly been affordable, secure, and stable, he said, but “it has been proved not [to be] the case”. Europe would now need to produce more of its energy itself, he went on, and “will produce a strong restructuring of our economy”. It is a very interesting speech and worth reading in full.

EU leaders have been debating responses to the energy crisis at a summit in Brussels. At the time of writing, they had not reached agreement on a plan to cap natural gas prices.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Offshore wind’s value proposition

Gavin Thompson — China must kick-start the green steel revolution

What would an accelerated energy transition mean for metals and mining?

Ben Hertz-Shargel — The grid edge of the future

Kate Mackenzie et al — The geopolitics of stuff

Benjamin Reinhardt — Making energy too cheap to meter

Eric Levitz — Throwing soup at paintings won’t save the climate

Quote of the week

“I recognise that it looks like a slightly ridiculous action. I agree: it is ridiculous. But we’re not asking the question: ‘should everybody be throwing soup on paintings?’ What we’re doing is getting the conversation going, so we can ask the questions that matter. Questions like: is it OK that Liz Truss is licensing over a hundred new fossil fuel licenses? Is it OK that fossil fuels are subsidised 30 times more than renewables, when offshore wind is currently nine times cheaper than fossil fuels? Is it OK that it is their inaction that has led us to the cost of living crisis, where this winter people are going to be forced to choose between heating and eating? This is the conversation we need to be having now. Because we don’t have time to waste.” — Climate activist Phoebe Plummer explained her reasons for throwing soup over Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers in the National Gallery in London. She said no damage had been done to the painting: it was behind glass and the soup could be wiped off.

Chart of the week

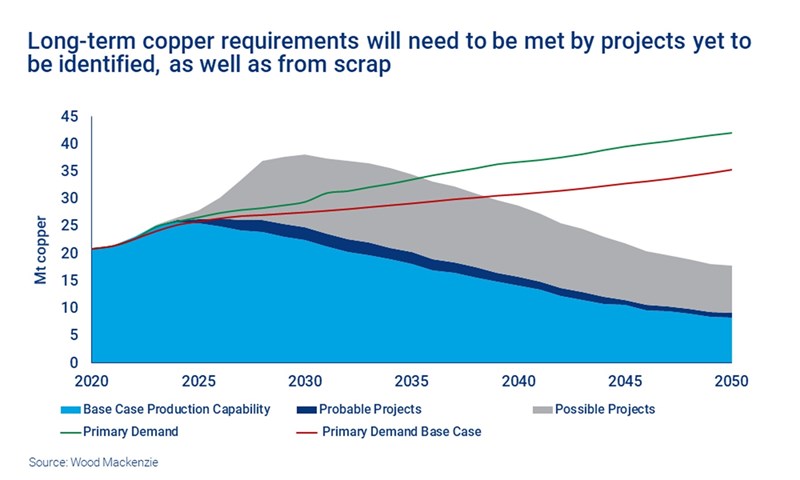

This chart showing the supply and demand outlook for copper comes from our recent dive into the consequences for metals of the transition to a lower-carbon global energy system. It makes clear that there is a significant challenge facing the copper industry in meeting the additional demand that we expect to be created. Even in Wood Mackenzie’s base case forecast, shown by the red line here, demand is expected to outpace supply from currently identified projects.

In a scenario for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, shown by the green line, as-yet unidentified projects would need to start contributing from the mid-2030s. The capital investment would be significant, matching the peak level of investment that we saw in the last boom period between 2012 and 2016, says Eleni Joannides, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for copper. The difference now is that that level of investment must be sustained over the next 30 years if there is to be enough supply to reach the zero emissions target by 2050. Future requirements for copper will also need to be met from scrap.