Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Washington tariff dispute creates uncertainty for US solar

Congress and President Biden are at odds over possible new duties on modules imported from Southeast Asia

10 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

The relationship between the US and China today, according to some foreign policy scholars, is similar to the mounting tensions between Sparta and Athens that led to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE. Sparta, previously the dominant regional power, watched with mounting concern as the power of Athens grew, and in the words of the historian Thucydides, “that made war inevitable”.

There are certainly some echoes of that ancient history in the ways that relations between the US and China have deteriorated in recent years. One significant difference from the world of Thucydides, however, is that the US and China are tied by the bonds of international trade. China is an important market for US exports, including oil and gas, and a leading supplier of manufactured products sold in America.

US policymakers from both Democratic and Republican parties say their country is “in competition” with China. But when they take action to try to curb China’s influence, disruption to those crucial trade links can have adverse effects. Strategies intended to enhance US national security can conflict with other policy goals.

Solar modules are a case in point. There has been a debate raging in Washington over whether to impose new tariffs on imported modules from four Asian countries — Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia — that use Chinese polysilicon wafers.

Supporters of imposing the import duties immediately, who are mostly but not exclusively Republicans, argue that the US needs to put up barriers so it can fight back against the Chinese solar manufacturing industry’s dominance of the global market. Opponents, including the Biden administration, argue that solar developers in the US need access to low-cost modules to support rapid growth in installations.

Both sides of the argument agree that the US needs to develop its own low-carbon energy manufacturing sector. That was one of the principal objectives of the Inflation Reduction Act signed into law by President Joe Biden last year. The disagreement is over the need for what President Biden calls “a 24-month bridge as domestic manufacturing rapidly scales up to ensure the reliable supply of components that US solar deployers need.”

As Sylvia Leyva Martinez, Wood Mackenzie’s senior analyst for North America utility-scale solar, puts it: “President Biden wants to push for a smooth transition to US manufacturing of solar modules. But that view is not shared by everyone in Congress.”

The roots of the dispute lie in an investigation launched by the Department of Commerce last year, looking at allegations that companies were producing solar cells and modules in Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia, using polysilicon wafers from China, to circumvent US anti-dumping and countervailing (anti-subsidy) duties.

In December, the department concluded that four of the eight companies being investigated were indeed “attempting to bypass US duties by doing minor processing in one of the Southeast Asian countries before shipping to the United States.” That meant any companies exporting to the US from those four countries would face significant additional duties, at rates of up to 250%, unless they could certify that they were not circumventing the duties already in place for imports from China.

However, before the commerce department had delivered its findings, President Biden pre-empted its conclusions. In June he signed an executive order declaring that the US faced an emergency over “the availability of sufficient electricity generation capacity to meet expected customer demand,” and that as a result, the administration would allow imports from the four Asian countries free of any additional duties for 24 months.

Now Congress is pushing back against that two-year delay. Last week the House of Representatives voted 221-202 to revoke the moratorium, and on Wednesday the Senate voted for the same measure 56-41. President Biden has pledged to veto the resolution, thus keeping the tariff moratorium in place, and it does not look as though his opponents have enough support in Congress to override that veto. But the votes show the strength of support for stronger measures targeting China’s exports.

Jason Smith, the Republican chairman of the House Ways & Means committee, said: “By shipping its products through Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, China has set up a solar panel export scheme that cheats American workers and consumers… We cannot surrender to China or any other country and put American workers at a disadvantage.”

The threat of the new duties, which could have been imposed retroactively to hit any imports after November 2021, had a significant impact on US solar installations last year. Along with disruption to imports created by panels being detained by US Customs and Border Protection under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, it contributed to a 30% drop in US utility-scale solar installations last year.

The CBP began releasing significant quantities of module shipments, mostly from Malaysia and Vietnam, in the fourth quarter of last year, and US solar installations are rebounding strongly this year. Wood Mackenzie expects total utility-scale installations of about 20 gigawatts for 2023, up from 12 GW in 2022, as previously stalled projects are able to make progress again.

However, Wood Mackenzie’s Martinez warns that the wrangling in Washington over duties is still creating difficulties for solar developers. “It is a very challenging time to be in solar procurement,” she says. “Everything can change in a day. It brings a lot of uncertainty and makes everything more complicated.”

This is a volatile time in US politics because of the crisis looming over the debt limit, which is likely to come to a head in the next few weeks. But disagreements over China, manufacturing and the solar industry are likely to persist well beyond that. The Biden administration’s implication is that the “bridge” to the emergence of robust US solar module manufacturing sector might need to be in place for just 24 months. That seems like an optimistic assessment.

The US has a very long way to go to build a solar module manufacturing industry to rival China’s. It has a global market share of about 2%, compared to 70% for China. US solar developers are likely to continue to need imported modules, despite the incentives for domestic manufacturing in the Inflation Reduction Act.

In some low-carbon energy sectors, the incentives in the IRA make US production highly competitive even against the lowest-cost imports, Wood Mackenzie research has found. But that is not really true for solar modules. Module manufacturers plan to invest in significant increases in production capacity in the US, but we think their expansion will not be enough to supply all forecast US demand. Capacity for critical components, including wafers and cells, will also have to be built from scratch. And modules from Southeast Asia could still be lower-cost than those produced in the US, even after the tax credits in the IRA. Additional import duties would be needed to make domestic manufacturing clearly the lowest-cost option.

The substantial labour cost advantages for Asian manufacturers mean that building a US industrial base for solar module production will always be an uphill struggle. For many other low-carbon energy products, such as solar trackers, it should be much easier to develop US manufacturing capacity. Given that, US policymakers might decide to accept continued reliance on imports to meet at least some of the country’s demand for solar modules.

History suggests that interfering with trade flows can be a dangerous move. Athens’ decision around 432 BCE to impose trade sanctions on the city of Megara, an ally of Sparta, is seen by many historians as a flashpoint that caused simmering hostilities to erupt into open warfare. In trade wars, as in real wars, it is always important to pick your battles carefully.

In brief

Oil prices have been continuing to decline, with Brent crude dropping to its lowest level in almost 18 months, despite the OPEC+ group’s announcement of production cuts a month ago. Worries about the strength of the global economy have been weighing on the market, particularly after the US Federal Reserve’s decision to raise interest rates again this week. On Friday morning Brent was trading at about $73 a barrel.

Tesla has reported its Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions for the first time. In its latest Impact Report, Tesla said its Scope 3 emissions were about 30 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent last year. Those emissions, mostly coming from the company’s supply chain, were orders of magnitude greater than the Scope 1 emissions from Tesla’s own operations, which were 202,000 tCO2e.

The New York state legislature has adopted a US$229 billion budget that includes three significant climate-related measures: a ban on fossil fuel-burning appliances in new buildings; a programme of permits for carbon emissions designed to raise money from companies; and new rules allowing the state-owned New York Power Authority to build and operate solar and wind projects.

Environmental groups in California have launched a legal action attempting to throw out the Public Utility Commission’s new rooftop solar incentives, which are significantly less generous than under the previous programme.

Hydrogen Europe, an industry group, has criticised European Commission Vice-President Margrethe Vestager over her argument that the EU does not need to match the subsidies for hydrogen in the US Inflation Reduction Act. In an interview with Danish business news magazine Finans, Vestager rejected the idea that the EU was competing with the US for investment in hydrogen. “If you want to be in the European market, the risk of moving production to the USA is not very great," she said. Other low-carbon technologies including wind, solar and storage are being allowed by the Commission to receive more generous treatment from national governments in response to the incentives included in the IRA.

Other views

Rachel Schelble — Oil and gas Majors: venture capital strategies for the energy transition

Robin Griffin — Future-facing commodities: your questions answered

Kan discovery in Mexico’s shallow water one of the largest since 2020

Adrian Lara and Marcelo de Assis — Gas resources in Latin America: the challenges to development

Peter Findlay — What’s shaping CCUS project costs?

John Madan — Could energy recovery solve the mounting problem of global waste?

Zion Lights — What might an energy-rich future look like?

Madison Hilly — Why nuclear waste is misunderstood

Matthew Wald — Dollars, sense, and Kilowatt Hours

Antonia Juhasz — Iraq gas flaring tied to cancer surge

Jule Koenneke and Steffen Menzel — Petersberg: An opportunity for Olaf Scholz’s climate credibility

Mitchell Ferman — The US shale oil capital won’t invest in itself

Quote of the week

“There still does need to be some investment in fossil fuels… If you look at our [Canadian] economy, look at the oil sands, and at other aspects of our fossil fuel economy, we need to make that competitive. Competitive is not just about cost, is it relatively low cost, and it's not just about risk, it's the lowest risk in the world, that's clear. But we also need to make it low carbon, and that's going to take very large investment.” — Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England, gave an interview to CTV News, in which he set out his views on the need for continued investment in fossil fuel production. Carney was a co-founder of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, which brings together about 550 banks, fund managers, insurers and other financial institutions committed to moving to net zero emissions. The members of GFANZ have been under pressure to commit to no new investment in fossil fuels.

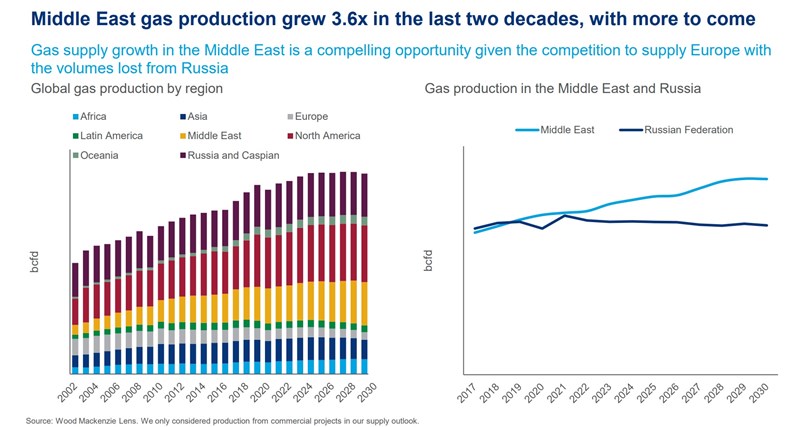

Chart of the week

This comes from a new note titled The Middle East Steps On The Gas, written by Alexandre Araman, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for Middle East Upstream research. There is an extract available for free download, with several interesting graphics, and this one sets the scene. The chart on the left shows global gas production by region, with surging output from the Middle East represented by the yellow bars. The chart on the right shows gas production from just the Middle East and from Russia. They have been roughly neck-and-neck, but for the rest of this decade we expect Russia’s gas production to stagnate, declining slowly, while in the Middle East output continues to increase, rising almost 20% by 2030. Wood Mackenzie’s Araman comments: “Gas supply growth in the Middle East is a compelling opportunity, given the competition to supply Europe with volumes lost from Russia.” Take a look at the full report for lots more detail.