Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Assessing the challenges ahead for carbon capture in the US

CCUS has great potential, but economics, regulation, and politics create some complex problems to be solved

12 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

John Bel Edwards, the governor of Louisiana, is an interesting figure in American politics. He is a Democrat, in a state that voted by 58%-40% for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. And although, in many respects, his policy agenda is what you would expect given his right-leaning voters, in some areas he is closer to the Democratic mainstream. His climate strategy includes a goal of net zero emissions for the state by 2050, and a Climate Action Plan setting out a programme for achieving those objectives.

One of the central planks in that strategy is carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS). The governor’s climate plan says it is expected to “play a critical role in decarbonising the global economy by addressing high-intensity and hard-to-abate emissions that will be necessary to reach net zero.” In that, he is aligned with President Joe Biden, who championed the Inflation Reduction Act that included increased tax credits for CCUS.

Last month, however, Governor Bel Edwards expressed impatience with the Biden administration, writing to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to complain that it had been slow to clarify the regulatory framework for the wells used to inject carbon dioxide into deep rock formations. Louisiana has asked for primacy in permitting and regulating these wells, known as Class VI wells, taking over responsibility from the federal government. The EPA has not yet made a decision on that application. The uncertainty has been holding up planned investments in CCUS in Louisiana, Governor Bel Edwards said.

The tension between state and federal governments is a reminder of the issues that still need to be resolved before the US can develop a successful carbon capture industry. Wood Mackenzie sees CCUS as an essential part of the toolkit for tackling climate change. In our new Global Net Zero Pledges Scenario, designed to show how the governments of the world that are aiming for net zero could achieve those goals, by 2050 CCUS accounts for about 15% of the total reduction in emissions relative to our base case forecast.

The Inflation Reduction Act, passed last year, acknowledged its importance, by increasing the value of the 45Q tax credit for different varieties of CCUS. The credit for carbon dioxide captured from industry and power generation and then used was increased from $35 to $60 a tonne. The credit for carbon dioxide captured from those sources and then stored in rock formations was increased from $50 to $85 a tonne. And the credit for carbon dioxide captured from the air and then stored in rock was increased from $50 to $180 a tonne.

The US currently has 23 million tonnes per annum of carbon capture capacity in operation, with a further 112 Mtpa planned. Wood Mackenzie analysts expect at least another 55 Mtpa of capacity to be announced as a result of those more generous incentives.

Louisiana will be a crucial test case for those expectations. The oil and gas industry is important for its economy: it is the third-largest gas-producing state in the US, and has the second-largest refining capacity. A governor who wants to reach net zero emissions without losing his state a lot of jobs and income has to think about how oil and gas assets and workers can provide lower-carbon energy. CCUS offers a solution.

Louisiana also has advantageous geology, with plenty of rock that would be suitable for storing carbon dioxide, most of it offshore in the Gulf of Mexico.

But for the investment to flow, critical regulatory issues including control of permitting for Class VI wells will need to be resolved. Two states, Wyoming and North Dakota, already have primary regulatory authority over those injection wells, and others including Texas, West Virginia and Arizona, as well as Louisiana, have been working on applying to the EPA to take primacy for themselves. The expectation is that state control will mean a more streamlined regulatory system and faster decisions on permitting, and Wyoming and North Dakota already seem to be in a strong position to attract projects.

The federal government in principle supports the idea of ceding regulatory primacy to the states. But in a letter to state governors last December, Michael Regan, the head of the EPA, warned that the administration wanted to be sure that vulnerable communities would not be harmed by CCUS. “Community residents have shared their concerns about the safety of [carbon capture] projects and worry that their communities may bear a disproportionate environmental burden associated with geologic sequestration,” he wrote.

While the Biden administration was “committed to supporting states’ efforts to obtain Class VI primacy,” he wrote, “states and EPA must work together to address these concerns and set a strong foundation of practices that will protect our most vulnerable communities.” Examples included “an inclusive public participation process” while developing a project, and possible mitigation measures such as protecting water sources.

The worries raised by the EPA reflect concerns about CCUS projects are starting to emerge in the US. Proposed carbon dioxide pipelines, such as the Summit Carbon Solutions system, which will gather carbon dioxide from ethanol plants in five midwestern states and deliver it for sequestration in North Dakota, have faced opposition from environmental campaigners. The campaigns are similar to the ones that have had great success in stopping oil and gas pipelines being built in recent years.

It is still uncertain how much extra cost and delays those concerns will add to CCUS projects in the US. But regulatory frameworks and the political environment are clearly going to be critical for the industry’s success or failure.

The economics of CCUS also remain complex, even with the more generous tax credits. The cost of carbon capture and storage from industrial sources in the US can range from about $35 per tonne at the low end to about $135 a tonne at the high end. And within those totals the costs of different stages of the process can vary widely.

For example, biomass fermentation during ethanol production produces a near-pure stream of carbon dioxide, which is relatively low-cost to capture. But the transport costs to collect the carbon dioxide from a large number of relatively small facilities and move it to the sequestration site will be high.

Because the new tax credits are guaranteed only for 12 years, when many projects will expect to keep operating beyond that, there is also uncertainty about their long-term economics. It is quite possible the US will have a carbon price in 2035 and beyond to support the economics of CCUS, but it cannot be guaranteed. To support the growth of carbon capture, it is important for the industry to bring its costs down further.

The key question for companies and investors is what types of project will be able to negotiate this challenging landscape most successfully. Peter Findlay, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for CCUS, says there are two broad types of approach emerging: plans for large-scale “hubs”, that aim to develop infrastructure to capture emissions from a number of sources, and smaller-scale projects that might have just a single point source and a single destination.

The hub approach, championed by ExxonMobil, makes it possible to take advantage of economies of scale, and could make a material difference to US emissions with just a single project. The drawbacks are the co-ordination problems facing a project that will necessarily involve several companies and require support from state, federal and local governments.

The birth of the US shale gas industry, led by smaller independent companies rather than the Majors, is a reminder of how a fragmented and highly competitive sector can sometimes innovate faster. Agility and diversity of approach, with big rewards for success, were the key to cracking the problem of how to produce shale gas at commercially viable rates. It is possible the costs of CCUS can be brought down the same way.

“These small CCUS projects are like onshore shale gas production, and the hubs are more like multi-billion dollar projects offshore,” Findlay says. “Is CCUS going to be more like onshore shale or offshore mega-projects? That is going to be a very important question.”

In brief

Tesla has agreed to open up part of its Supercharger and Destination Charger network in the US to non-Tesla electric vehicles for the first time. It will make at least 7,500 chargers, including at least 3,500 Superchargers along highway corridors, available for all EVs by the end of 2024. Drivers of non-Tesla EVs will be able to access the chargers using the Tesla app or website. President Joe Biden hailed the move as “a big deal, and it'll make a big difference”.

The White House revealed the agreement with Tesla as part of a series of announcements intended to show progress towards the president’s goal of 500,000 EV chargers across the US. Other companies including BP, Hertz and General Motors also announced plans to expand their charging networks. The build-out is being supported by US$7.5 billion of government money, committed in the bipartisan infrastructure law passed in 2021. Some of that money will go to Tesla to pay for conversions and construction to meet its pledge on open-access chargers.

BP announced a collaboration with Hertz to build a US network of fast chargers. The network will cover Hertz locations in cities including Atlanta, Austin, Boston, Chicago, Denver, Houston, Miami, New York, Orlando, Phoenix, San Francisco, and Washington, serving car rental customers, rideshare and taxi drivers, and the general public at high-demand locations such as airports. BP plans to invest US$1 billion in EV charging in the US by 2030.

BP also announced a US$1.3 billion deal to buy truck stop chain TravelCenters of America, which operates at about 280 locations in 44 states. BP said the deal would help its convenience store and EV charging operations towards their target of more than US$1.5 billion of EBITDA in 2025, and their aim of more than US$4 billion EBITDA in 2030.

Ford has suspended production of its electric F-150 Lightning truck, after a fire started by a battery fault in a vehicle in a holding lot, several news outlets reported. A company spokeswoman said: “We have no reason to believe F-150 Lightnings already in customer hands are affected by this issue.” The company told the Jalopnik blog that “it believes it has already identified the issue and plans to plans to wrap up its investigation at the end of next week.” It added that production should restart “in a few weeks’ time.”

Governor Phil Murphy of New Jersey has set a target that 100% of the electricity sold in the state should come from zero-carbon sources by 2035. He is also aiming all new cars and light-duty trucks sold in the state to be zero-emission vehicles by the same date.

Russia has requested a meeting of the UN Security Council to discuss journalist Seymour Hersh’s claim that the US and Norway sabotaged the Nord Stream gas pipeline system last year. As I noted last week, the story has a pretty fundamental weakness in its attribution of motive to the US: it does not seem to fit the facts of the pipeline’s operations as we knew them. Now the independent analyst Oliver Alexander has published an investigation picking holes in several of the details in Hersh’s story.

Other views

Simon Flowers — The Edge: How India is redefining its energy future

Gavin Thompson — Asia’s nuclear power surge

Renewable power competitiveness in Asia Pacific worsened in 2022

Alan Gelder — What do ExxonMobil exits mean for the oil Majors?

Irina Wang — 10 years ago, we were turning nuclear bombs into nuclear energy. We can do it again

Robert Zullo — Across the country, a big backlash to new renewables is mounting

The International Renewable Energy Agency — Global geothermal market and technology assessment

Robin Mills and Ahmed Mehdi — The EU ban on Russian oil: crude implications for the Middle East

Derek Brower and Amanda Chu — The US plan to become the world’s cleantech superpower (This is an interesting piece that makes good use of Wood Mackenzie insights and data)

Quote of the week

“Europeans didn't freeze, and we really hoped for that.” — Olga Skabeyeva, a Russian television presenter and supporter of President Vladimir Putin, expressed disappointment that mild weather had meant Europe had been able to avoid severe hardship over the winter, despite the steep drop in gas imports from Russia.

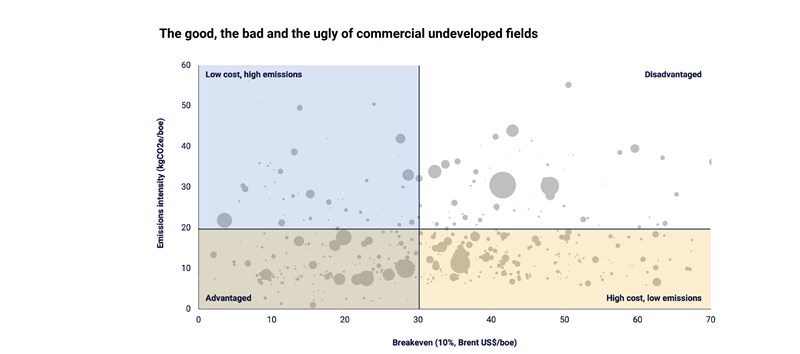

Chart of the week

This comes from an important new report by Andrew Latham, Wood Mackenzie’s vice-president of energy research, titled Scraping the barrel: is the world running out of high-quality oil and gas?. It looks at the issue of “peak advantage”: meaning a world in which oil and gas resources that are advantaged, in the sense of having both low production costs and low Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions, are strictly limited. The point is not that the world is running out of oil and gas: we actually have more than enough just in discovered resources to meet expected demand out to 2050 and beyond, although there will have to be heavy investment to bring those resources into production. But there is a real issue with the affordability (defined by low costs and breakeven prices) and the carbon intensity (defined by low scope 1 and 2 emissions) of that oil and gas.

The chart, sourced from Wood Mackenzie’s Lens platform, illustrates the point. It includes fields approved or justified for development and that are economically viable. Bubble size represents the field’s reserves, with largest bubble representing 11.4 billion barrels of oil equivalent. Emissions intensity is the average for Scope 1 and 2 over field life. Breakeven is the Brent price needed to achieve a 10% internal rate of return.

The advantaged resources are the ones down in the lower left quadrant with both low emissions intensity and a low breakeven price. Only 28% of the resources in commercial undeveloped fields (49 billion boe) are advantaged in terms of breakeven below US$30 Brent, with emissions intensity of less than 20 kgCO2e/boe.

The full report goes into a lot more detail on the dimensions of the challenge and possible responses. If you are at all interested in the future of the global oil and gas industry, it’s essential reading.