Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

The US oil Majors set the pace in the Permian Basin

ExxonMobil and Chevron, flush with cash, have set out their plans for growth in oil and gas production in Texas and New Mexico

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

When Exxon relocated its headquarters from New York to Irving, Texas, in 1989, it was seen as taking advantage of the new flexibility offered by modern technology. “If you have a good fax machine and a decent airport, it doesn't matter where you are,” a relocation consultant commented to the New York Times.

Thirty-three years later, ExxonMobil has decided that, even in an age of somewhat more sophisticated communications technology, there are benefits to having top management co-located with large parts of the business. It is relocating its headquarters to its ultra-modern Spring campus, north of Houston, which has space for more than 10,000 people. The company said the move, part of a wider drive to streamline its corporate structure and cut costs, would “enable closer teamwork to accelerate and increase value delivery through company-wide approaches”.

The importance of Texas to ExxonMobil was underlined by another statement from the company this week. On a call on Tuesday to discuss the group’s fourth quarter earnings, chief executive Darren Woods said he expected ExxonMobil’s production in the Permian Basin to rise by about 25% this year, continuing the pace of growth seen last year.

It was confirmation of a point that Wood Mackenzie analysts have been making for a while: this year, the US Majors will outpace their smaller rivals, the listed independent companies, in production growth in the Permian, the most important of the North American tight oil plays. For these global companies, some of their most advantaged assets are in their own home territories.

Mike Wirth, chief executive of Chevron, said on its earnings call last week that its Permian production would rise by about 10% this year. That is slower than for ExxonMobil, but still faster than the growth Wood Mackenzie expects for the leading listed independent E&P companies, which have overall held their production roughly flat over the past two years. “These growth numbers are probably double or triple what the listed independents are going to do,” says Robert Clarke, vice-president of upstream research in the US.

The two largest US oil groups are riding high at the moment. ExxonMobil’s shares are up 76% over the past year, rising more than 6% on Tuesday alone. Chevron’s are up 55%, over a period in which the S&P 500 index is up about 20%. ExxonMobil generated free cash flow of about $31.6 billion in 2021, while Chevron made a record $21.1 billion. With Brent crude around $90 a barrel and Henry Hub gas around $5 per million British Thermal Units, the strong cash generation is set to continue.

Much of the cash is going into debt reduction, share buybacks and increased dividends. Chevron has increased its quarterly dividend by about 6%, and ExxonMobil by about 1%. But there is also more available for ramping up production. Chevron’s total capital and exploration budget for 2022 is $15.3 billion, up about 30% from last year, while ExxonMobil’s is rising by about 36%, to about $22.5 billion.

Significant proportions of that additional investment are being channeled into the Permian Basin. Chevron plans to spend $3 billion in the region this year, up from $2 billion last year. It expects to bring a little over 200 wells into production, an increase of about 50%. The step-up in activity reflects efficiency improvements in Chevron’s operations, “and just the quality of this asset, which endures as we go through cycles like the one we just went through,” Wirth said.

ExxonMobil has listed the Permian as one of its priorities for increased investment this year, along with Guyana, chemical performance products and project restarts in its downstream businesses. It has not specified how much it plans to ramp up activity, but it is sticking to its target of producing 700,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day in the Permian by the end of 2024, up from an average of about 460,000 boe/d last year. Chevron has reaffirmed a goal of 1 million boe/d in 2025, up from an average of 608,000 boe/d last year.

To stay on course for those goals, both companies will have to run more rigs and complete more wells. “Spud and completions activity at 2021 levels gets neither company to their stated production target,” Robert Clarke wrote last year.

The leading listed independent producers will say more about their plans for spending in the Permian when they report fourth quarter earnings over the coming month. But it seems likely that continued capital discipline and pressure to return cash to investors will mean they will not try to match the Majors’ growth, despite the returns available from new wells. Some privately-held operators are definitely growing faster, but that fast-growing group of companies controls only about 15% of Permian production.

For ExxonMobil and Chevron, as they make decisions on global capital allocation, the Permian is an attractive location. New wells generate a lot of cash and have quick paybacks. ExxonMobil said this week that the Brent price it needed to cover its capital spending and dividend from cash flow in 2021 was $41 a barrel, and would average just $35 a barrel between now and 2027, helped by its latest round of cost reductions. Both companies are also producing increasing volumes of gas as well as oil in the basin. Until recently, that might have been a drawback, but with gas prices rising and US LNG exports expected to keep growing, it has become another attraction.

The US Majors’ Permian production also has relatively low greenhouse gas emissions compared to their other assets. For ExxonMobil, emissions intensity in the Permian is 42% below the average for its upstream portfolio, and for Chevron it is 36% lower. Moves to cut emissions such as curbs on methane leakage and the end of routine flaring in the Permian, which ExxonMobil expects to achieve this year, will increase that advantage still further. ExxonMobil is planning for net zero emissions from its Permian operations by 2030.

Next year will mark 100 years since Santa Rita #1, widely considered the first discovery in the Permian Basin, was drilled about 50 miles south of Midland, Texas. A century later, it is still of critical importance to the US oil and gas industry in general, and the Majors in particular.

Georgia Power plans exit from coal

Tom Fanning, chief executive of Georgia-based utility group Southern Company, has been a long-standing defender of coal. “We must place a high priority on developing solutions that preserve this critical energy resource for the future,” he told a US Chamber of Commerce event in 2011. Since then, however, wind and solar generation has soared in the US, and confidence in the long-term availability of gas supplies has grown. And Southern’s Kemper project, intended to be the first large-scale coal plant with carbon capture in the US, proved a costly failure.

This week, Southern’s Georgia Power subsidiary submitted an Integrated Resource Plan to state regulators, proposing to retire all of its coal-fired power plants by 2035, and most of them by 2028. The company said in a statement that “coal-fired generation continues to be less economically viable, and its proposals would “thoughtfully transition its fleet to more economical, cleaner resources”. More than 3.5 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity would be closed by 2028 under the plan, to be replaced by about 2.4 GW through new power purchase agreements with gas-fired plants, and 2.3 GW of renewables.

Some environmental campaigners complained that the plan included such a large contribution from gas to replace coal. Charline Whyte of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign in Georgia said: "Georgia’s electric system and energy infrastructure must be transformed to rely on renewable power like solar and battery storage rather than replacing one fossil fuel with another.” The state’s Public Service Commission gets to rule on the plan, and could require Georgia Power to add more renewables, as it did in 2019.

However, Ryan Sweezey, Wood Mackenzie’s research manager for North American power markets, pointed out that unlike some other utilities that have been winding down their coal generation, Georgia Power is planning to replace the capacity through contracts with existing gas-fired plants, rather than investing in new ones.

The plan is another sign of how the economics of power generation in the US have shifted against coal, regardless of any further pressure from federal climate policy. Coal-fired generation capacity in the US is expected to drop from about 200 GW this year to only about 50 GW in 2032 and effectively zero in 2042, in Wood Mackenzie’s base case forecasts.

Even if President Joe Biden does not get to pass any legislation or implement any new regulations, the US power industry’s exit from coal is already being hastened by existing regulations such as the Environmental Protection Agency’s rules on the disposal of coal combustion residuals, finalised at the end of 2014.

In brief

The Biden administration has alleged that Russia is considering staging a fake attack on its own troops, to use as a pretext for potential conflict in Ukraine. A spokesman for the US state department said it was publicising the allegation “to dissuade Russia from continuing this dangerous campaign, and ultimately launching a military attack."

President Vladimir Putin accused the US of ignoring Moscow’s concerns about its security and using Ukraine as “a tool” to contain Russia. However, speaking after talks with Viktor Orban, Hungary’s prime minister, President Putin said he was ready to continue negotiations with the west. Orban said that at their meeting, he had asked President Putin to increase supplies of Russian gas to Hungary by 1 billion cubic metres per year. That increase would “secure Hungary’s energy supply permanently” and allow the government to continue to hold down costs for Hungarian consumers, Orban said.

March TTF gas futures were trading on Thursday at about €81 per megawatt hour, equivalent to about $27 per million British Thermal Units. That is roughly half the price at its peak last December, but still more than four times its level of a year ago.

The UK government announced a subsidy of £350 a year per household to help consumers with soaring energy bills. For most consumers, energy bills are subject to a cap administered by the regulator Ofgem, which can be adjusted twice a year. Ofgem said the next cap, which takes effect in April, would on average rise by £693 per year to £1,971 , a 54% increase.

A group of ten Democratic senators, including Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey, has written to US energy secretary Jennifer Granholm, urging her to “take swift action to limit US natural gas exports”. The call is a direct challenge to the strategy of the Biden administration, which has been encouraging US and other LNG suppliers to send more cargoes to Europe if the tensions over Ukraine cause further disruption in flows of gas from Russia. The senators say the administration “must also consider the potential increase in cost to American families.” The senators do not call for an immediate ban on exports from existing LNG facilities, but say the administration should “develop a plan to ensure natural gas remains affordable for American households”, and consider halting approvals for new plants until that plan is in place.

The OPEC+ countries held their regular monthly online meeting, and reportedly kept it to a record time of just 16 minutes. The meeting agreed to stick with the scheduled increase of 400,000 b/d in production limits for March. The statement from the meeting reiterated “the critical importance of adhering to full conformity” with the production limits. Increasingly, the problem seems to be countries under-producing rather than over-producing relative to their quotas.

PJM Interconnection, which operates the power grid across 13 US states from New Jersey to Kentucky, has proposed a two-year delay in reviewing requests for connections from developers, to help it work through a huge backlog of applications, Inside Climate News reported. The grid operator has proposed reforms to its approvals process to prioritise projects that are closest to being ready to start construction, but also needs to “take a pause” on reviewing about 1,250 projects, mostly for solar generation, and defer consideration of any new requests until the fourth quarter of 2025. The backlog reflects the fact that interconnection policies were designed to handle a few requests from large plants, not the thousands of requests from smaller renewables projects that have been flooding in to PJM and other regional grid operators.

Texas has been bracing itself for another bout of freezing weather, a year after the devastating cold that caused days-long blackouts and led to hundreds of deaths.

And finally: how an oil fortune helped push back the frontiers of mathematics. Oil wealth has always been diverted into other areas, from photography to public health, and from art museums to football clubs. The New York Times this week shed light on another field where oil money is said to have had a powerful impact: proving Fermat’s last theorem. The theorem was first written down by the French mathematician Pierre de Fermat in 1637, but remained unproven until Andrew Wiles of Oxford university cracked it in the early 1990s. James M. Vaughn Jr, a Texas oil heir, told the Times that his Vaughn Foundation Fund had since the 1970s been giving millions of dollars to researchers and conferences looking at the theorem, helping to revive interest in the problem and build a community of scholars. “We solved the problem,” Vaughn told the Times in an interview. “If we hadn’t put the program together as we did, it would still be unsolved.”

Some mathematicians have expressed scepticism about Vaughn’s claim that “we” solved the problem. But it is certainly true that breakthroughs in fields from drama to particle physics are more likely to come when you have a community of people working on a subject, rather than a lone genius toiling in isolation. James M. Vaughn has until now said little publicly about his support for mathematical research, but at 82 is thinking about his legacy and wants some credit for what he has done. It would seem churlish to deny him that.

Other views

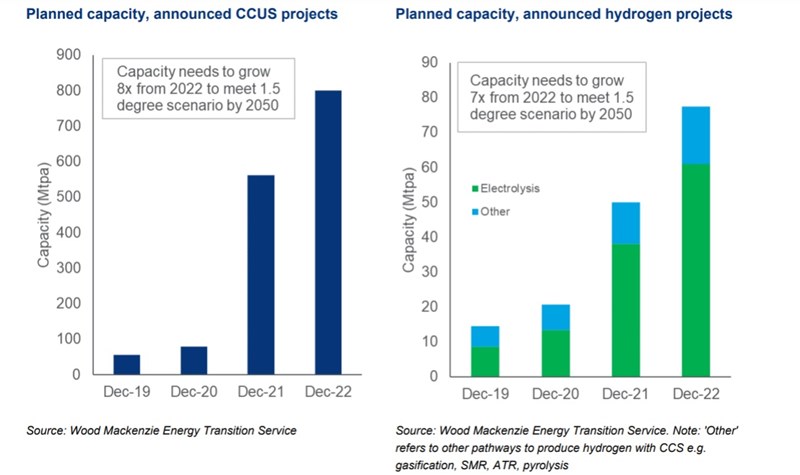

Simon Flowers — The coming carbon capture and storage boom: we have lift off

Pablo Prudencio — Will private operators keep pushing Permian production higher?

Jason Bordoff — Don’t blame Putin for Europe’s energy crisis

Noah Smith — A New Industrialist roundup

Hans-Werner Sinn — Green nuclear power

BlackRock Investment Institute — Managing the net zero transition

Quote of the week

“The energy market has faced a huge challenge due to the unprecedented increase in global gas prices, a once in a 30-year event, and Ofgem’s role as energy regulator is to ensure that, under the price cap, energy companies can only charge a fair price based on the true cost of supplying electricity and gas. Ofgem is working to stabilise the market and over the longer term to diversify our sources of energy which will help protect customers from similar price shocks in the future.” — Jonathan Brearley, chief executive of Ofgem, the UK energy regulator, explained why the cap on household energy bills would be rising by 54% from April.

Chart of the week

This comes from a new report on the outlook for carbon capture and hydrogen, from Wood Mackenzie’s Mhairidh Evans and Flor Lucia De la Cruz. It makes two very clear points, for carbon capture on the left and low-carbon hydrogen on the right. First: interest in both these technologies has been soaring, with many more projects announced and coming on stream. Second, even after that surge in investment, both technologies still have a very long way to go to achieve the scale they will need to play a significant role in putting greenhouse gas emissions. They would need to grow many times over to put emissions on a path to meet the Paris goal of trying to limit global warming to 1.5 °C.