Get this complimentary article series in your inbox

1 minute read

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

Latest articles by Julian

-

Opinion

Metals investment: the darkest hour is just before the dawn

-

Opinion

Ebook | How can the Super Region enable the energy transition?

-

The Edge

Can battery innovation accelerate the energy transition?

-

Featured

Have miners missed the boat to invest and get ahead of the energy transition?

-

Featured

Why the energy transition will be powered by metals

-

Featured

Could Big Energy and miners join forces to deliver a faster transition?

To the uninitiated, rugby is a technical and complicated game. As young schoolboys it was all a wee bit confusing and we invariably ended up on the wrong side of the score line. However, we had a wonderful Welsh coach called Billy, who, when the chips were down, would always roll out his go-to phrase: “back to basics!”

These wise words seem quite pertinent right now. With COP26 underway, the world awaits tangible evidence that the huge expense and carbon footprint of the conference will be worthwhile. With that in mind, delegates do need to go back to basics in terms of what must be achieved: clear commitments that will put us on the pathway to net zero.

Of course, many will collectively shrug their shoulders, expecting nothing to change as a result of COP26. As the wonderful French phrase has it, plus ça change – the more things change, the more they stay the same. Unfortunately, though, maintaining the status quo is not an option this time.

Beware of the mining talent gap

I’ve previously highlighted the implausibility of carbon emission reduction by 2030 that is consistent with achieving net zero by 2050. The deck is very much stacked against mining companies, who are aware of the challenges of developing supply, yet investors, policy-makers and wider society are seemingly unwilling to assist in enabling faster development. Greater recycling will undoubtedly be part of the solution, but primary extraction will carry the lion’s share of the load.

Even if all these stars were to align, the sheer number of projects that would need to be developed concurrently presents a new problem: it would stretch the capacity of every function required to deliver them. A perfect storm of demand for all disciplines, from mining engineers to regulatory and permitting departments, suppliers and contractors, would make the challenge insurmountable.

To understand the scale of the challenge, consider the number of current mining engineering undergraduates. In its 2020 report on student and faculty numbers in mining and engineering programmes, Mining Education Australia forecast that the number of students graduating in 2022 will total just 46. For comparison, between 2012 and 2016 (arguably the peak of the last supercycle) more than 250 mining engineers graduated each year. That means the supply of new talent will have fallen by 85% since 2012. In the US the situation is little better: a total of 182 students were awarded a BSc in Mining Engineering in 2020, down 51% compared with 2015.

Digitalisation will enable higher productivity but that will only mitigate some of the challenges created by the lack of qualified talent. As specific mine output becomes lower an ever-greater number of assets will be required to deliver a given tonnage.

The danger of metals supply inelasticity

Long lead times and a lack of advanced projects also create supply inelasticity – even if there was a desire to accelerate supply and the available talent to deliver it.

Lead times for mine projects for many metals are stretching out to more than 10 years from first discovery to first delivery. (At Wood Mackenzie’s recent Global Energy Summit, for example, Mark Cutifani, CEO of Anglo American, noted that lead times are as much as 12-13 years.) What’s more, meeting ESG requirements is no longer optional, with regulation and scrutiny becoming ever more stringent.

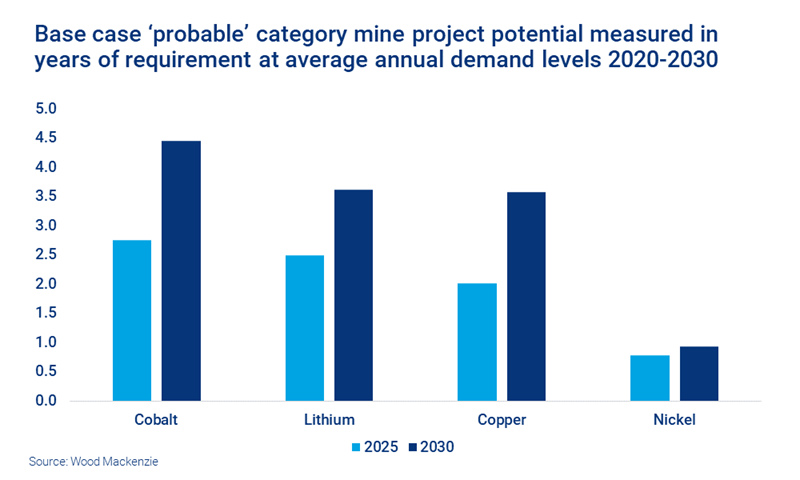

Across the industry, the pool of advanced projects for several commodities is remarkably thin. This in turn means there is limited supply elasticity to allow for demand to accelerate. In the case of copper, ‘probable’ category projects could add a further 0.9 Mt of supply by 2025, and 1.6 Mt of capacity by 2030 – assuming these projects were to be sanctioned now. Taking annual average growth in requirements at the mine level between 2020 and 2030, that’s equivalent to two and three-and-a-half years of supply respectively.

The ratios are similar for cobalt and lithium. Nickel stands out as having the least supply elasticity, with a tiny probable mine project pipeline of less than one year of requirements. These figures are cold comfort for consumers.

Addressing the decarbonisation-growth paradox

Currently, the various decarbonisation pathways under consideration create a desperate need to accelerate the supply of resources along the value chain. Paradoxically, this will lead to higher emissions, as we cannot decarbonise mining faster than we can grow supply –at least for the next decade.

Of course, regardless of what happens in mining, under our current economic model growth makes the whole world go round. Convention has it that the global economy will continue to grow out to 2050; in fact, under our base case Energy Transition Outlook (ETO), Wood Mackenzie forecasts it to double in size between 2020 and 2050.

This has dramatic implications for the need to decarbonise. Current CO2 intensity per unit of GDP is around 0.4 kg, which should fall to 0.2 kg by 2050. Under an accelerated 1.5 °C pathway, carbon intensity needs to fall to less than 0.05 kg per unit of GDP – an extremely challenging target.

Given the immensity of the challenge, perhaps we need to take a different approach by addressing what is a relatively unconstrained consumption model. If global economic growth were to be constrained more than we are currently assuming, the knock-on effect would be a reduction in the need to lower CO2 intensity per unit of GDP. That should be more manageable for the whole supply chain. The shortage of metals and mining projects at the advanced stage necessary to meet an accelerated energy transition scenario would become more manageable.

What I’m really saying is that we may need more time in the short term to get after faster decarbonisation in the longer term. As I see it, an accelerated energy transition scenario within the timescales currently envisaged is at the extreme end of plausibility, if not impossible. Urgent action is needed to address this, and it starts with the basics – acknowledging that capacity in all areas of the development of primary mining, metals processing and recycling infrastructure needs to be expanded.

To quote Francis of Assisi: “Start by doing what's necessary; then do what's possible; and suddenly you are doing the impossible.” Policy-makers convening at COP26 should take note.

Get unique metals and mining insight in your inbox

This article is part of a series exploring opportunities and challenges in the world of metals and mining. Fill in the form at the top of the page to be alerted to new articles as they are published.