Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Resource nationalism and energy transition metals

Moves to maximise revenue as demand accelerates

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

View Simon Flowers's full profileAnthony Knutson

Global Head, Thermal Coal Markets

Anthony Knutson

Global Head, Thermal Coal Markets

Anthony is the global head of our thermal coal markets research for the Metals and Mining group.

Latest articles by Anthony

-

Opinion

Harris v Trump: A fork in the road for US energy

-

Opinion

How do Western sanctions on Russia impact the global metals, mining and coal markets?

-

Opinion

Decarbonising metals and mining: three key strategies to win the emissions battle

-

The Edge

Resource nationalism and energy transition metals

-

Opinion

Golden opportunities to drive down mining and metals carbon emissions

-

Opinion

Battery raw materials: tracking key market dynamics

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin oversees our Europe, Middle East and Africa research.

Latest articles by Gavin

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

Upside pressure mounts on US gas prices

-

The Edge

The coming geothermal age

In his opening address to the Ghana Mining Expo earlier this year, Samuel Abu Jinapor, Minister for Lands and Natural Resources, stated that Ghana’s goal for its mining sector is “... to retain a significant proportion of the value chain of these future and other critical minerals in our country.”

Ghana, with significant resources including gold, bauxite and manganese, is far from alone in seeking to maximise the value of its minerals and avoid past resource grabs by foreign players. For developing nations in particular, the playbook is increasingly focused on resource nationalism.

What is resource nationalism? What does it mean for the mining majors? And can importing countries rise to the challenge? Anthony Knutson, Principal Analyst, Metals and Mining, and Gavin Thompson, Vice Chair APAC Energy Research, take a closer look.

The next era of resource nationalism

While not new, the message from the Ghanaian minister is echoed across the developing world. Many nations have already modified their resource development policies.

A key part of this is a move down the value chain. Countries have introduced mandatory requirements for miners to process ore and purify production domestically before intermediate products can be exported. Indonesia has led the way, with an export ban on raw minerals forcing companies to invest in domestic smelters to export their mined nickel. With its nickel export revenues soaring, Indonesia’s success is seen as a benchmark for other countries to follow.

In June this year, Namibia followed in the footsteps of Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) by banning the export of unprocessed energy transition minerals including lithium, graphite and cobalt. Gabon has recently announced its intention to follow a similar path.

In the DRC, the development of copper resources by Ivanhoe Resources and China’s Zijin Mining Group will require those companies to build a smelter in-country to maintain an export permit. Similarly, Nigeria last year rejected Tesla’s lithium mining request unless this was backed by a domestic battery facility.

This more muscular approach isn’t only happening in developing economies. In Chile, the government is taking a page from its own copper book with plans for the partial nationalisation of its lithium industry.

Mining majors yet to fully respond

Western mining majors have long been cautious around new high-risk supply opportunities. For most publicly listed miners, capital discipline still trumps ‘speculative’ growth – including investment in greenfield transition metals. Such is the scale of their legacy businesses, moving the investment dial on what are relatively small incremental energy transition plays becomes a challenge.

Rising resource nationalism won’t improve this. Western politicians may have woken up to the risks of under-investment in critical minerals, but participation in new supply by the mining majors and investors is yet to match the ambition of governments in the west.

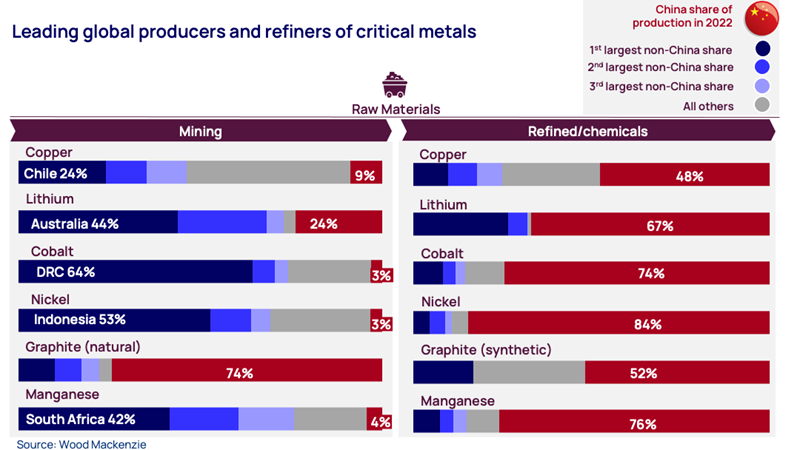

China’s continuing dominance of critical minerals

With the mining majors’ pool of low-risk greenfield opportunities coming up short, China continues to take major stakes in the production, processing and use of critical minerals. More immune to ESG risks and less spooked by resource nationalism, Chinese miners continue to spend big: the country has invested US$35 billion in Indonesian nickel supply and processing over the past four years alone.

And this influx of new capital isn’t limited to China. Other developing economies are also ramping up investment in critical minerals supply, including Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund.

Can Western countries rise to the challenge?

The G7 countries all have critical metals production goals, and several have the mineral resources that can help support this.

Policy support has been forthcoming. In the US, for example, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) offers major financial incentives for critical minerals extracted and processed domestically. In a telling shift, the US Department of Energy added copper to its Critical Materials Assessment, opening the door for mine project tax credit eligibility under the IRA. A greater challenge is likely to be overcoming local opposition and permitting challenges to get processing and smelting facilities built.

The complexity of resource development is also leading to a more global approach, with mutual friendships now extending into the arena of mineral development. The Minerals Security Partnership includes the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, several European countries and, most recently, India, “to bolster critical mineral supplies.” Key to this is ensuring minerals are produced and processed to the economic benefit of producing countries – a move to counter the push towards resource nationalism. But with few of the developing world’s major resource holders at the table, more work is required.

The energy transition begins and ends with metals. All countries seeking to secure critical minerals must work in closer collaboration with resource holders to ensure an equitable share of proceeds so that future supply is delivered at the pace and scale required. Without this, the transition will stall.

LME Forum 2023

Securing metals supply in a rapidly changing landscape | 11 October, in London

Register now