Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Biden and Xi build bridges on energy

After years of deteriorating relations, the US and China have opened new paths for communication and cooperation on energy and climate

10 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

Pandas could be on their way back to the US. Panda diplomacy is one of the oldest, as well as the most endearing, instruments of Chinese foreign policy. And when it was confirmed in September that the pandas Mei Xiang, Tian Tian and Xiao Qi Ji would leave the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington DC before the end of the year, it was the latest evidence of an increasingly frosty relationship with the US.

However, China’s President Xi Jinping suggested last week during his visit to the US that a new pair of pandas could be sent to replace them, possibly to San Diego Zoo. Both countries have been making a clear effort to rebuild relations, holding the first meeting between President Xi and President Joe Biden for a year, on the sidelines of the APEC Summit in San Francisco.

A joint statement on energy and climate, including commitments to accelerate the deployment of renewables and to work together on reducing emissions, was one of the most significant policy outcomes of that more amicable relationship. With the COP28 climate talks in Dubai approaching at the end of the month, the improved alignment between the US and China is a positive sign for hopes that fresh momentum can be injected into the transition to low-carbon energy.

The US and China have competing interests in many areas, to the point that some commentators have raised the question of whether the two countries are ultimately “destined for war”. But they also have many shared interests, not least in tackling climate change. They are the world’s two largest emitters, between them accounting for about 44% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions from energy and cement, according to data from the Global Carbon Project. (Split about 31% for China and 14% for the US.) They have both the greatest responsibility and the greatest opportunity for tackling global warming.

The first five-year Global Stocktake of progress on climate, which will conclude at COP28, will underline that the world is not on course to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement , including limiting global warming to 1.5 ˚C. A Technical Dialogue paper for the stocktake warned in September: “While action is proceeding, much more is needed now on all fronts.”

Commenting last week on a new United Nations analysis of national plans for reducing emissions, Simon Stiell, Executive-Secretary of UN Climate Change, reinforced the message. “Governments combined are taking baby steps to avert the climate crisis,” he said. “COP28 must be a clear turning point. Governments must not only agree what stronger climate actions will be taken but also start showing exactly how to deliver them.”

That assessment echoes the view set out in Wood Mackenzie’s Energy Transition Outlook. The pathway we are on today, as reflected in Wood Mackenzie’s base case forecast, is likely to mean global warming of about 2.5 ˚C, compared to pre-industrial times, by the end of the century.

Prakash Sharma, our vice-president, for scenarios and technologies, says shifting to a 1.5 ˚C pathway would be possible but “extremely challenging”, especially in the current geopolitical situation. The war in Ukraine has underlined the extent to which the global economy still depends on fossil fuels for energy security. If the world is to achieve that 1.5 ˚C goal, “much depends on actions taken this decade”, he says.

Against that background, there were some encouraging indications from last week’s joint US-China statement on energy and climate, drawn up after meetings in Beijing and California between John Kerry, the US special presidential envoy for climate, and his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua. The two countries reiterated their support for tripling renewable capacity globally by 2030, and pledged to accelerate deployment in their own power sectors to deliver “meaningful” reductions in emissions from electricity generation before the end of the 2020s.

They also committed to drawing up Nationally Determined Contributions — the emissions reductions plans submitted to the UN — that would be aligned with the Paris goals of limiting global warming to “well below” 2 ˚C and “pursuing efforts” to limit it to 1.5 ˚C. Past NDCs were judged by the Climate Action Tracker, a research group, to be “insufficient” for the US and “highly insufficient” for China to achieve those Paris goals.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the statement, however, is that it revives both the principle and the practice of cooperation between the two countries on energy and emissions. China has agreed to revive the Working Group on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s, which was launched in 2021 but was blocked last year after Nancy Pelosi, then Speaker of the House of Representatives, visited Taiwan. The working group will focus on areas including the energy transition, methane emissions, the circular economy, and deforestation.

Several other collaborative efforts are also being revived, including the US-China Energy Efficiency Forum, dialogues and exchanges on energy policy and strategy, and cooperation on decarbonisation at the sub-national level.

On methane, there will be technical working group dialogues, solutions exchanges, and capacity building to support efforts to cut emissions. The initiatives will help China implement its new national action plan for reducing methane emissions, which was announced back in 2021 and finally published earlier this month.

The two countries also aim to advance at least five large-scale cooperative CCUS projects each by 2030.

There is a difficult balance to be struck in energy and climate policy between national and global thinking. National or regional imperatives are often vitally important for the energy transition. Governments want to support low-carbon technologies to create jobs, attract investment, develop internationally competitive industrial sectors and strengthen energy security.

But a go-it-alone strategy for energy and manufacturing can mean missing out on the benefits of international trade, including being able to source the lowest-cost equipment, components and materials from around the world. And there is no point in a small number of countries trying to cut emissions if others are just going to let them rip.

For much of his administration, President Biden has tended to focus on the national reasons for wanting to accelerate the energy transition. In his State of the Union address to Congress in February, the president mentioned “jobs” 23 times and “climate” just three times. China was mentioned five times, on each occasion as a competitor to the US. Under his leadership, he said, the US was “investing in American innovation and industries that will define the future that China intends to be dominating.”

The agreements reached last week show the possibility of an alternative set of relationships between the US and China, where collaboration is possible as well as competition. At the very least, there are several new channels of dialogue, which should be beneficial to both countries and to the progress of decarbonisation globally.

Not everything went smoothly last week. President Biden at one point described President Xi as a “dictator”, a comment that was condemned by China’s foreign ministry and drew a visible wince from US Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Despite that awkward moment, however, the talks were generally judged a success.

It remains to be seen whether the pandas really do come to San Diego, and whether all the warm words about energy dialogue and cooperation ever amount to very much. But for several years the risk has been growing that the US and China would be unable to work together, even to tackle the shared threat of climate change. Now at least the door has been held open.

In brief

The libertarian candidate Javier Milei won a convincing victory in Argentina’s second-round presidential election, and will be sworn in as head of the government on December 10. He will now have a chance to implement the radical reforms that he has championed as answers to the country’s severe economic problems, including inflation running at an annual rate of 143%. Wood Mackenzie analysts Adrian Lara and Vinicius Moraes commented earlier this month that macroeconomic stability was critical for realising the unconventional oil and gas potential of the Vaca Muerta formation. That will be a critical issue to watch as the new president implements his programme.

The OPEC+ group of countries will reportedly consider further cuts in production at their next ministerial meeting on November 26, following the recent slide in oil prices. Benchmark Brent crude was trading at about $81 a barrel on Monday morning, down from a peak of over $97 in September.

Octopus Energy, the UK-based energy retail and technology company, has launched a £3bn fund to invest in offshore wind. Tokyo Gas is the first investor, with a cornerstone investment of £190 million. The fund is being set up to invest in “development, construction, and operational stage offshore wind farms, as well as companies creating new offshore wind,” and will focus on projects in Europe.

The fund is being launched as the offshore wind industry is going through a difficult period, squeezed by supply chain problems and rising interest rates. The UK government announced last week that the maximum prices available for offshore wind in next year’s Contracts for Difference auction would be increased by 66%, to £73 per megawatt hour, in the hopes of encouraging more developers to bid.

Regulators should require US utilities to use grid-enhancing technologies to save customers money, Allison Clements, a member of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has said.

Elon Musk’s Starship rocket again exploded soon after launch, on its second test flight. At the first launch, in April, the rocket blew up about four minutes after takeoff. This time Starship flew for about eight minutes, reaching a height of about 90 miles, and the Super Heavy booster separated successfully from the Starship spacecraft. However, SpaceX said that soon after the separation, both the booster and the main craft suffered “rapid unscheduled disassembly”.

Other views

Elena Belletti and others — Mission invisible: Tackling the oil and gas industry's methane problem

Simon Flowers — WoodMac’s Gas, LNG & Future of Energy conference: five key takeaways

Samantha McGarvey — Why are US distributed solar customer acquisition costs still on the rise?

Australia sees record volume of upstream M&A deals, despite regulatory turmoil

Vinicius Moraes and others — Can Colombia navigate the energy transition?

Alan Gelder and Kendrick Ng — Survival of the fittest refineries

Huaiyan Sun — How will China’s expansion affect global solar module supply chains?

Brian Dabbs and others — Three takeaways from Biden’s big transmission plan

Tyler Norris — Beyond FERC Order 2023: Considerations on deep interconnection reform

Clint Rainey — “ESG cartels”: Anti-woke Republicans are weaponizing antitrust law

Kate Marvel — I’m a climate scientist. I’m not screaming into the void any more

Quote of the week

“Oil has been weaponised from time to time since it became a traded commodity, so we’re always worried about that, working against that, but I think so far it hasn’t… We have two active wars in the world, one involving the world’s third-largest producer [Russia], the other in the Middle East where missiles are flying near where oil is produced, and yet prices are near the lower point of the year.” — Amos Hochstein, President Biden’s senior adviser for energy and investment, told the Financial Times that he did not expect Arab oil-producing countries to try to use oil as a strategic weapon, despite anger over Israel’s siege of Gaza.

Chart of the week

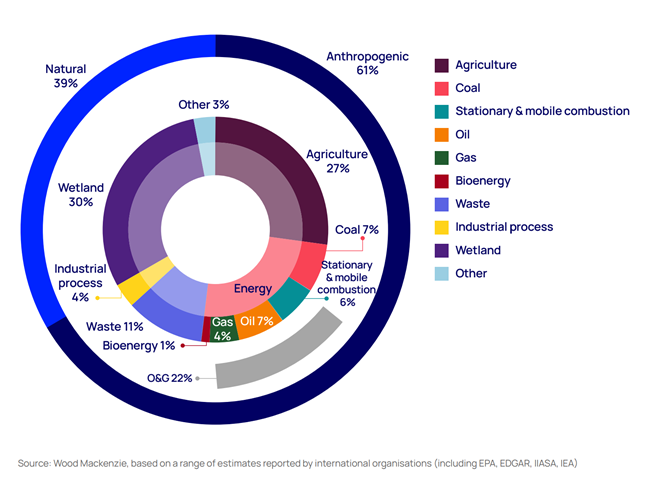

This comes from Wood Mackenzie’s new Horizons paper: Mission invisible: Tackling the oil and gas industry's methane problem. It shows the sources of the methane that escapes into the atmosphere, giving an immediate insight into the dimensions of the problem.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, responsible for almost a third of the emissions-induced increase in global temperatures since the start of the industrial era. But only about 60% of all methane emissions result from human activity. And within that segment of anthropogenic emissions, only about 22% come from the oil and gas industry.

There have been huge strides made in recent years by oil and gas companies in terms of focusing on fugitive methane. The leading US and European oil companies, along with Saudi Aramco, Petrobras and CNPC, last year launched the Aiming For Zero methane emissions initiative, pledging “to do what it takes to reach near zero methane emissions in their operations” by 2030.

This chart suggests similar initiatives are needed for agriculture and other sectors as well.

Want to hear more from Ed on the hottest topics in energy?

To subscribe to the Inside Track, our weekly round-up of news and views from WoodMac experts, fill in the form at the top of the page.

You can also listen to the Energy Gang, a bi-weekly podcast hosted by Ed Crooks, available wherever you find your podcasts.

2024 APAC Energy & Natural Resources Summit

9 May 2024 | Marina Bay Sands, Singapore

Book your tickets now